Reshuffles are never as exciting as you expect. Big beasts are rarely sacked, young rogues rarely promoted, and the diversity just isn’t there. To misquote Blackadder, normally the only lasting thought is “what does the Lord Privy Toast Rack even do?”

After Theresa May’s latest reshuffle, 28 people now attend cabinet. Labour’s shadow is no smaller. Bar the brief period following mass resignations in June 2016, Jeremy Corbyn has regularly had over 30 members in his top team. But effective government doesn’t need crowded cabinets. Winston Churchill’s wartime grand coalition only had eight members, Harold Macmillan’s first just 17.

Changing politics however have meant changing cabinets. After Tony Blair’s 21 members, Gordon Brown was the first prime minister to make cabinet two-tier, with 27 to squeeze in. Meanwhile, Barack Obama’s was only 17, for a country five times the size.

It was the 2010 coalition that really caused headaches for parliamentary furnishers. Single parties have increasingly struggled to reward each of their political factions with cabinet positions let alone two. Musical chairs with eurosceptics, orange-bookers, one-nation Tories and left-leaning democrats put David Cameron’s first cabinet at 29 – his last was 33.

Coalitions across the channel seem to manage. Angela Merkel in her last grand coalition only had 16 officials. The 22 ministers in Denmark, a minority three-party coalition, even make do without any junior ministers.

Beyond party factions, and coalition proportionality, prime ministers have increasingly used cabinet positions as political favours. Blair used cabinet to reward acolytes like David Miliband, whilst Brown used it to mollify critics. Staring at the Brexit abyss, May used three new positions and departments to quickly make her look less remain-oriented.

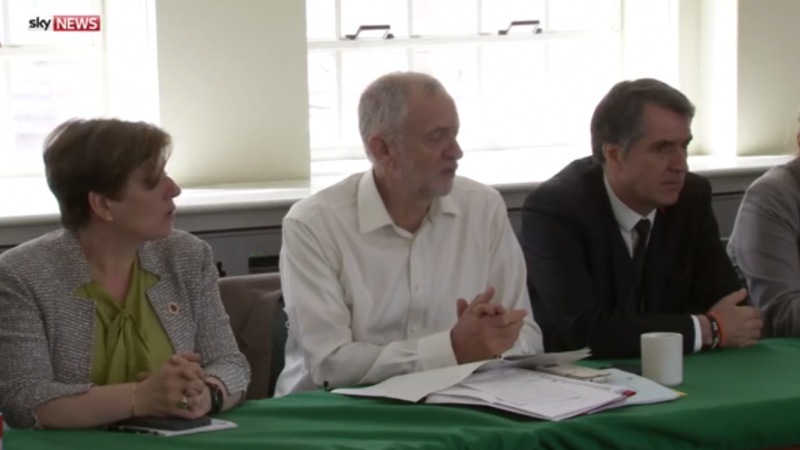

Cabinet positions are also used to show commitment to issues like climate change and international development. Corbyn has rewarded campaign groups by elevating housing, mental health and social care and voter engagement to the top tier.

Oversized cabinets are a problem. Beyond salaries, new ministries multiply costs. There’s day to day expenditure of running offices, strategic reviews, and everything else that needs duplicating. Whilst saving money is beneficial, it’s still small fry compared to other government spending. Although the cabinet manual has no limit on size, the “ministerial and other salaries act” prevents there being more than 21 salaries at secretary of state level.

A much larger problem is the paralysis of decision making. Agreement between 30 people is far harder than among 15. As May has found out in debating a post-Brexit vision for Britain, rewarding each party faction makes detailed proposals impossible. There’s no reason to suppose Labour would be any different. Expanding cabinets are emblematic of Britain’s productivity crisis and poor management skills.

More ministries also mean more siloed decision making, and greater effort spent trying to join them up. Would Labour’s housing ministry really be able to work effectively independently from Communities and Local Government? Bold political statements don’t result in effective and efficient government.

Unity also becomes a thing of the past. As seats multiply, each position loses value and individual weight. Ambitious ministers are left fighting for anything that can raise their profile. Sunday mornings become internal briefing wars rather than a single political narrative. Even unintentionally more cabinet ministers are more likely to contradict one another.

In his next reshuffle Corbyn could make a clear statement that Labour believes in effective government. A smaller cabinet, that still represents Labour’s broad church can do this.

It might cause some uproar, but a committed unionist wouldn’t need separate positions for each devolved government. Doubling up these roles as Blair did, or Corbyn last year, didn’t impede policy.

Interest groups may not like it but big political issues don’t require cabinet seats to be solved. International development and culture could be represented by the foreign office and business department respectively. Health and social care has suffered from a chronic lack of join up, separate ministries don’t help that.

The worst offender though is the chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, or minister without portfolio. Party politics should be well away from government, and a spare seat for a party chair is completely inappropriate.

Finally, spare a thought for the Queen. Every cabinet minister automatically becomes a member of the privy council. With the average length of ministerial tenure down to less than a year and a half, privy is no longer the key word.

More from LabourList

‘National flags and identity can be inclusive – we’re right to embrace them’

Revealed: Claims of bullying, misogyny and harassment in Young Fabians

‘Sunak’s claim of a ‘sick note culture’ is immoral and deeply flawed’