“History is written quickly, and pundits like to make out as if every result was inevitable,” wrote the Spectator’s editor Fraser Nelson on election night. That was one pre-election forecast that has been proved correct. Many now write with magnificent certainty about how hopeless Labour’s strategy was. Not all will have been quite so sure on Wednesday and Thursday last week about the inevitability of the result. Rooms had been booked for coalition negotiations, and sandwiches had been ordered. It was optimistic perhaps, but not actually delusional, based on the available polling evidence, that a much better result was about to emerge. It didn’t. Look at the numbers. The strategy did fail, and Labour received a shellacking.

Pat McFadden set out in sober detail what went wrong on the Westminster Hour last night. One of his main points was that an attempt had been made to “game” the electorate by building up a winning coalition of support. He argued, rightly, that Labour’s appeal has to be bigger and more positive than that.

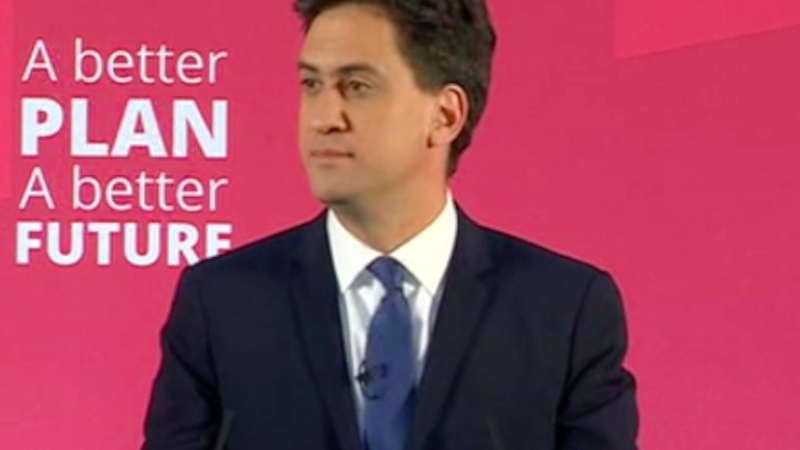

Having been supportive (though not uncritical) of the leadership’s approach over the past four years, I have to accept what McFadden said. What is still worth disputing is the idea (not raised last night by the member for Wolverhampton South East) that Ed Miliband’s leadership has constituted “five wasted years”.

A moderate and in truth pretty non-scary policy programme was caricatured as being dangerously left wing. The caricature should have been challenged more effectively, but it wasn’t. Criticism of bad business practice should have been balanced with at least as much praise for success stories. But is worrying about homes, pay, the NHS, apprenticeships and poverty too left wing? It would be an odd claim to make.

Then there is the problem of Labour’s lack of economic credibility. A short, simple answer to the charge of having “spent too much” was never found. Few serious economists really think the last Labour government adopted a reckless fiscal position. Having a balanced budget did not save Spain or Ireland when the banks started to fall. But the public seemed to prefer the non-economist’s version of events being offered by Osborne to the sophisticated and accurate account provided by Ed Balls. The perception became the reality as far as most were concerned.

The impact of old media, not so much on their remaining readers as on the broadcasters, was also significant. Miliband was right to defend his father’s reputation against the dreadful slurs printed in the Daily Mail. It was one of his finest moments as leader. And while a principled stand against the actions of the News of the World was also correct other colleagues, such as Tom Watson and Chris Bryant, could have been left to lead the criticism of News International, as it was then called. Never go to war with people who buy ink in industrial quantities, they used to say, and it turns out to be good advice still.

Much more study will be made of what was actually happening in voters’ minds, in different parts of the country, in the final months before polling day. Different views are already being circulated. For how long was Labour’s level of support being overstated? When did the long-awaited crossover take place? The voting intention polls do not really tell us. The lack of movement seemed to indicate that, while there was still a gap on the economic competence and leadership scores, this had nonetheless been “priced in”. Perhaps everyone has already forgotten, but all the agonising and analysis last week had to do with which party would have a better claim to govern, not a pre-mortem discussion of how badly Labour were about to do. The one outstanding and honourable exception to this is of course every LabourList reader’s favourite Telegraph commentator Dan Hodges, who consistently (and accurately) predicted disaster for Labour for four and a half years.

My guess – and it is merely a guess for now – is that only when the SNP scare started to be drummed in did sentiment begin to shift. So even while Labour was being praised for running a good campaign, with Miliband himself surpassing expectations, the result was finally slipping away. LibDems were imploding under the weight of well-aimed (and well-funded) Tory attacks. Maybe without the SNP scare those sandwiches would have been needed after all.

I agree with Steve Richards: “The slogan ‘Sorry we blew it last time. Vote Labour’ does not sound like a winner to me,” he wrote in the Independent a couple of years ago. The Eds were, intellectually and even morally, incapable of pretending to believe that Labour’s public spending had been out of control. But perhaps this was an argument that Labour was never going to win. Five years after being kicked out it was still too soon for a return. More dust had to settle. The symbolism of Balls’ cruel defeat on election night may, painfully for him, be part of that process. As it was, falling petrol prices and a supermarket price war may have done more to make voters finally feel a bit better off than anything the government had done. That wasn’t inevitable either.

The outbreak of criticism over the weekend shows how disciplined and loyal the party had been in the preceding few years. It also gives a taste, I think, of the likely reaction had a new party leader in September 2010 attempted to say that the last Labour government’s spending decisions had been wrong. The destructive row would have started then instead of now. It would have been no easier to avoid the same election result that has just been delivered.

It was a terrible defeat. The new leader has to start building a new big tent, with room for a very wide range of people. A new conversation has to begin. It can be done. And so, as Labour said in 2005, when it won a 67 seat majority with 35% of the vote (and, by the way, losing in England then too): forward, not back.

More from LabourList

‘A third way approach is needed to protect children online’

‘Lammy’s jury trial cuts risk worsening racial bias in justice system’

‘Is there an ancient right to jury trial?’