As the healthy debate about Labour’s policy on withdrawal from Europe continues, it is worth noting how the history suggests there can probably never be a policy that will suit all of the Labour movement.

During the work for our book, How to Lose a Referendum: The Definitive Story of Why the UK voted for Brexit, Jason Farrell and I discovered much that surprised us. My research on the political history of Britain in Europe found that while we know the Conservatives have constantly been torn apart by Europe, the Labour Party has also had to manage many splits during that time.

There were few splits in 1950 when the Labour government decided to turn down the invitation to join negotiations to create the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) in 1950. Put into historical context, it seems understandable that a government trying to create a “new Jerusalem” of the welfare state, NHS and full employment was not interested in having a supranational authority making decisions for it on coal and steel production.

Labour were out of government from 1951 to 1964, during which time Britain applied to join the EC, in the early 1960s. The conditions included accepting tariffs and other restrictions on Commonwealth imports. This led to Labour leader Hugh Gaitskell making a rousing speech at the 1962 Labour conference in which he invoked the contribution of Commonwealth soldiers in the two World Wars and argued that the loss of sovereignty would be “the end of a thousand years of history.” He received a standing ovation, including from the left of the party, with whom Gaitskell had done battle on Clause Four and nuclear disarmament, leading his wife Dora to remark worriedly that “all the wrong people are cheering.”

By 1967, as it became clear that the long economic boom in the UK might be coming to an end, prime minister Harold Wilson decided to try a second application to the EC. This was turned down even before negotiations by de Gaulle, who argued that Britain was fundamentally not ready to join the EC.

Wilson left the application on the table, and after the demise of de Gaulle, new president Georges Pompidou opened the door for Britain to reactivate it in June 1970. Wilson thought he would be there to do that, calling an early election for June 18 1970, which of course Labour lost, leaving Edward Heath, the most Europhile prime minister the country has ever had, to take things forward.

This was the background to the nearest that Labour have come to a leader being removed because of Europe. The unions, Labour members and the increasing proportion of left-wingers in the parliamentary party after 1970 wanted him to go further. They saw the EC as a capitalist cartel, a “rich-man’s club” that could take powers of economic management away from a British government and make socialist planning in Britain impossible.

Conference in 1971 saw Labour adopt the specific policy of voting against entering Europe, only to see deputy leader Roy Jenkins walked through the “Aye” lobby with 68 other Labour MPs to vote with the Tory government and Britain joined the EC. Once this happened, some at the Labour conference wanted to commit Britain to withdraw if they won the next election. Wilson threatened to resign, which was when Tony Benn’s idea of a referendum to be held on EC membership instead became official Labour policy.

Labour won in 1974, and the referendum was held in 1975, with Wilson conceding an “agreement to differ” among his ministers. But when the result of the national vote came through, 67-33 in favour of staying in, it was thought the matter might be closed.

Of course, we now know that it was far from closed. Under Michael Foot the Eurosceptic left pushed for and achieved a commitment in the 1983 election manifesto to withdraw from the EC without a referendum should they be elected. This was one of many reasons for the actual breakaway that saw the Gang of Four form the pro-EU Social Democratic Party.

From that point began the march to Europhilia that remains Labour policy for the moment. Neil Kinnock started it by being involved in the invitation of European Commission president Jacques Delors to the TUC conference in 1988. The trade unions offered an open door to Delors as a third Thatcher victory had made them concerned about the possibility of a parliamentary route to social and employment protection. Delors pointed out that the EC now had the ability to guarantee these rights, and was greeted with a standing ovation and a chant of “Frère Jacques”.

Tony Blair was the most Europhile prime minister the country had seen since Edward Heath – and a far better communicator. He decided to engage positively with the European integration process, signing the Amsterdam and Nice treaties which created the conditions for EU enlargement and opened the country to Eastern European immigration in 2004 by not imposing transitional controls on migration. The problem was that domestic political pressures – and possibly a “pact” with Rupert Murdoch – stopped Blair from ever properly selling the EU or the benefits of immigration to the British people.

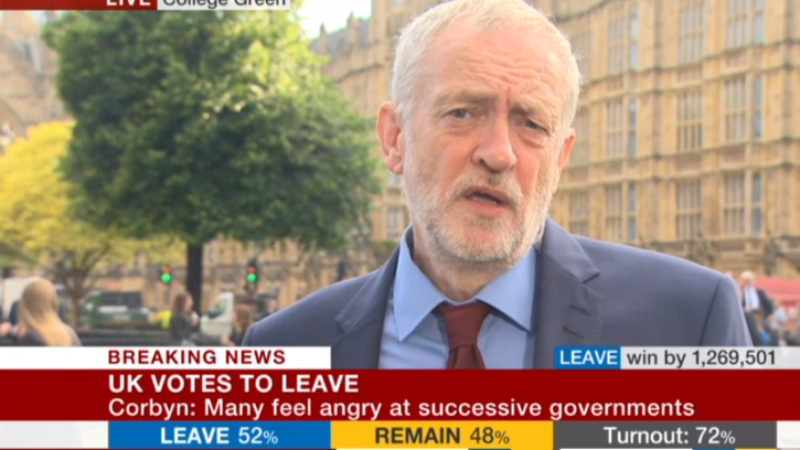

As Jason travelled around the country during the 2016 referendum campaign, he found many Labour voters in the party’s heartlands who had decided to vote for Brexit long before Jeremy Corbyn became leader. The reasons are many and varied, and include concerns over immigration and sovereignty as well as a feeling that politics had left them behind. Corbyn’s prevarication over Europe is not simply down to his own views, but his continuing need to serve all the parts of his “progressive alliance”, not just the most vocal ones.

Paul Goldsmith is a politics and economics teacher at Latymer Upper School in London and co-author, with Sky News senior political correspondent Jason Farrell, of How to Lose a Referendum: The Definitive Story of Why the UK Voted for Brexit – published by Biteback.

More from LabourList

EXCLUSIVE: Usdaw General Secretary writes to PM ‘frustrated’ regarding changes to Employment Rights Act

Think tanks and MPs call for targeted response as Iran war impacts cost of living

‘This Labour Government needs to fix the Tory student loan fiasco’