Labour’s popular manifesto, coupled with chants of “Oh, Jeremy Corbyn”, seems to have won the hearts and minds of Britain’s Youth. Well over 60 per cent of under-24s voted Labour at the general election and turnout among this age group was higher than ever before, which is an amazing result. Some have said that students were bribed into voting Labour with the promise of free university tuition fees, as if somehow students are the only group of voters not allowed to vote in their own interests.

When Corbyn brought up unfair Tory tuition fee hikes at prime minister’s questions last week, Theresa May mentioned that was Labour who introduced tuition fees, as if £9,000 worth of debt and nearly £30,000 worth of debt are even remotely comparable.

However, the PM unwittingly committed a massive faux pas in criticising Labour for introducing tuition fees. In doing so she was criticising the entire idea of tuition fees and especially raising them to unprecedented levels. Either Labour’s introduction of tuition fees was a good idea, which the Conservatives improved upon, or it was a bad idea to begin with; from a Conservative perspective, there can be no middle ground.

It is also fair to say that Labour have had a substantial change in direction since the days of tuition fees, so criticising Corbyn’s Labour for this policy will fall totally flat, especially since the leader voted against it all those years ago. Labour are now committed to scrapping fees.

However, even with this in the manifesto, Labour still won’t have gone far enough. Voter turnout amongst the young, while higher than it has been for a long time, is still about 10 per cent lower than the national average. That 10 per cent can make all the difference at the next election.

The watchdog, known as the Office for Fair Access, recently published a report revealing a shocking statistic: the number of students from a disadvantaged background dropping out of university after their first year has reached a five-year high, whereas their counterparts from a wealthy background have a dropout rate significantly lower.

While there is no doubt the prospect of ever-increasing debt is a significant factor, the snowballing cost of living faced by students arguably has a larger impact on the lives of students. Undeniably, this is caused by excessive rents charged by universities for accommodation. A rule of thumb is that one should spend a third of your income on rent, and while this has been long-discarded as mere fantasy for the majority of modern Brits, for students it couldn’t be any further from reality.

An NUS Unipol survey from 2015 showed that the average cost for university run student accommodation is £5,800 a year, which has surely risen since. This is around 70 per cent of the maximum maintenance loan, just a tad more than our apparent common-sense rule. When university related costs such as art supplies or transport are included, students are left with a meagre £27 to live on. Maybe we should ask the universities minister Jo Johnson to try living on that?

Why is it that universities can charge such extortionate rents? There are two things that need to be considered. Firstly, that new halls of residence are now being built in conjunction with universities and business partners, essentially by private finance initiative, and we all know how well those worked with hospitals (ie they didn’t). The profit-before-people ethos of these pseudo-PFIs leads to unnecessary luxuries in student flats, such as en-suite bathrooms by default.

The major draw for these developers is the second consideration. Student accommodation is an effective monopoly, at least when considering first year students, so service providers can charge what they want.

If you haven’t been to university in a while or don’t have a child who has, remember that results day, when prospective students find out if they’ve got into their preferred university, gives students the first sense of certainty as to where they will be living for the next three years. It is only a month from the beginning of term, when young people move to a new town or city, with few friends, and little time, giving students a very narrow opportunity to organise a home in the private rented sector, which may be of a lower cost.

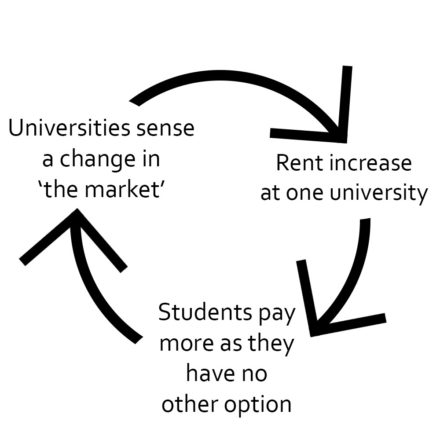

These monopolies operate like small cartels, using “market changes” to justify further price increases in something I like the call, “the rent cycle’ (pictured below). One set of accommodation increases price, which is paid because of the lack of options, so providers seize the opportunity to raise their prices, repeat ad nauseam.

The truth is that there is no market, just small monopolies independently raising their prices and making the position of students increasingly precarious, especially those whose parents cannot financially support them.

While students and students’ unions are doing their best to negotiate a better deal, there’s only so much they can do, considering that universities hold the balance of power in these negotiations. Labour need to step in and make the changes in government to rectify this injustice.

The answer is relatively simple: put strict controls on university-run accommodation. These controls should be tied to the level of maintenance loan (or loan plus grant, if Labour’s manifesto pledge is fulfilled) available. Pledging to make university life more affordable for a wider number of students will widen support amongst two key demographics. It is certain to shore up Labour’s base amongst young voters, but it will also break through to their parents, who are likely to be in their 40s and 50s, and who often struggle to support their children through university.

Appealing to these two key voter demographics could push youth turnout to parity with the rest of the population, and win over key Conservative-voting parents, whose likelihood of voting Labour is currently significantly lower than their children, at around 50 per cent. This policy could place Labour in a strong position to get into government in the not-too-distant future.

Labour needs to focus on more than student debt and making university life affordable for all students.

Oliver Price is a Labour activist in Hertfordshire.

More from LabourList

‘What Batley and Spen taught me about standing up to divisive politics’

‘Security in the 21st century means more than just defence’

‘Better the devil you know’: what Gorton and Denton voters say about by-election