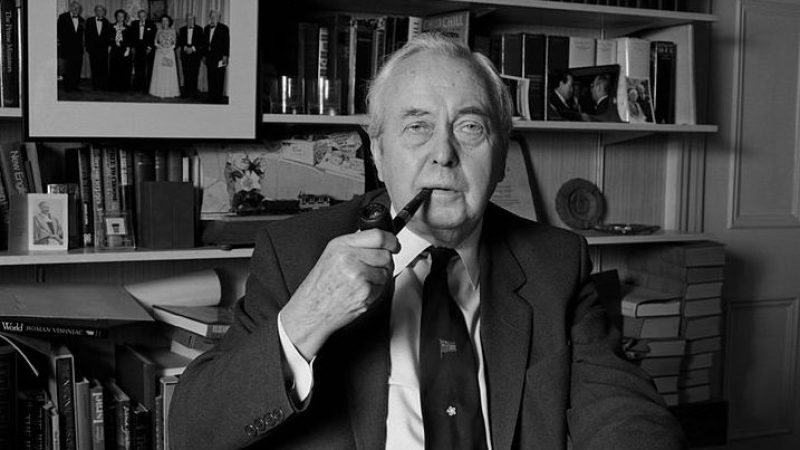

Nick Thomas-Symonds’ new biography of Harold Wilson is titled The Winner, which should give you a fair idea of the author’s thoughts about Labour’s third Prime Minister. He is pro. Thomas-Symonds’ book is a lively account of the life and politics of Wilson, the Yorkshire grammar school boy who won a still unmatched four general elections for Labour in 1964, 1966 and twice in 1974. Wilson was born in 1916, and the book follows him from his childhood in the north of England to his academic success at Oxford, his war years as a civil servant at the National Coal Board, into parliament and up through the ranks to Downing Street.

Thomas-Symonds writes with brio and a clear passion for his subject. He also has a fine eye for the funny, strange details that bring accounts like this to life – from Wilson’s PPS, a former electrician, debugging his room for him on ministerial trips to the Soviet Union, to the then Prime Minister’s insistence on having backbench MP Eric Moonman attend a Downing Street dinner given in honour of NASA’s Apollo 11 crew shortly after the moon landing in 1969.

Despite being the focus of the book, Wilson remains somewhat obscure throughout. Thomas-Symonds describes him as adaptable, ferociously clever and hard working, with a self-awareness rare in politicians, and writes that his politics were much motivated by his early experiences of his father’s periods of unemployment and the precarity that the family faced as a result. The author also makes a convincing case for Wilson as quietly feminist, having many trusted women allies whom he did not view as different to the men around then, and as meaningfully interested in racial equality.

Despite the detailed picture painted, the descriptions never quite cohere into a firm image of the man, and he is harder for the reader to picture than many of the vivid characters who surround him, including his unusually powerful political secretary Marcia Williams and the erratic George Brown, who served as Wilson’s Foreign Secretary. One suspects this has more to do with Wilson’s carefully curated public face than Thomas-Symonds’ skill as a biographer.

Ben Pimlott wrote what is widely regarded as the definitive biography of Wilson in 1992. I think it is safe to say that Thomas-Symonds’ work will not take the place of Pimlott’s as the default text on the subject. That does not mean, however, that it is not a fine book in its own right and one that sets outs its points of differentiation from Pimlott clearly. Thomas-Symonds has, he writes, access to papers that Pimlott did not, and he states that he wishes to counter Pimlott’s views on the later Wilson governments, offering more positive assessments of their achievements. His book – popular in tone, but surprisingly rigorous, particularly given the scale of Thomas-Symonds’ commitments elsewhere – is, I think, able to stand up these counter-assessments. If you are looking for the critical version of the uncritical case for Wilson, this is it.

Thomas-Symonds, in detailing Wilson’s handling of a variety of events, would seem to draw implicit comparison with later politicians fumbling their handling of similar situations. Most notable among these is Wilson’s approach to American pressure on Britain around the Vietnam war and his renegotiation of Britain’s membership of what was then the European Economic Community. Unless you’re a historian of modern Britain, you likely do not think very much about what Wilson did in these instances – but anyone who pays attention to politics knows what Tony Blair did when presented with American pressure to join a foreign war or how David Cameron’s pre-referendum renegotiation of EU membership terms ultimately panned out. The lesson Thomas-Symonds seemingly wants one to draw is: when you do it well, no one notices. You can see why this is a principle he might wish to see applied more broadly.

Of course, people read books by serving politicians to understand the author’s political positions and thinking, as much as they do to learn about the book’s topic. Many regarded Thomas-Symonds’ period as Shadow Home Secretary as something of an enigma. It was unclear whether he was ably subordinating his personal politics to the demands of the leadership or whether they were so perfectly aligned that no tension emerged between the two (or was he, in fact, just busy writing his surprisingly rigorous biography of Harold Wilson, which in being better than it has any right to be does feel a little like the long-form equivalent of posting 40 Instagram stories while on a work Zoom call).

Whatever the case may be, many felt his period in the office to have been politically milquetoast. Thomas-Symonds’ clear admiration for Wilson – for his path through the acrimonious Bevanite/Gaitskellite clashes of the 1950s and for his ability to manage and be in touch with the party (Wilson’s instincts, Thomas-Symonds takes the trouble to cite Michael Foot as noting, were “those of the party rank and file”) – would suggest he at least views himself as decidedly of the (soft) left. There is some space, one feels, between the politics Thomas-Symonds admires, and the politics we have seen him practice. Nonetheless, if the biggest criticism of a political biography one can draw is that it tells you more about its subject than its author, it can hardly be viewed as a failure.

More from LabourList

Almost half of Labour members oppose plans to restrict jury trials, poll finds

‘How Labour can finally fix Britain’s 5G problem’

‘The University of the Air – celebrating 60 years of Harold Wilson and Jennie Lee’s vision’