Our relationship with tax has changed. For decades tax was simply the means of paying for the spending that growth permitted within our economy. Labour or Conservative, but most especially under Labour, current tax income pretty much balanced current tax spending over time and government borrowing was used to pay for investment in our schools, hospitals and other infrastructure. That was, pretty much, the political consensus on tax whatever the appearance might have been.

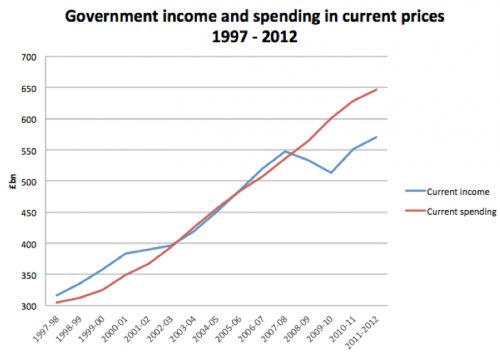

The following graph of current income and spending since 1997 shows this:

Source: HM Treasury budget data 1998 – 2012

As the graph shows, until 2007 Labour ran a surplus on tax income over current government spending. More importantly though, the graph shows that when the crash happened it was not because of overspending, but because tax income collapsed. That happened because the banks collapsed, and with them activity in the economy at large also collapsed, so less tax was paid. That’s why we got a recession.

But that is also why our relationship with tax has changed: the tax equation that once pretty much balanced doesn’t anymore and there’s not a person in the UK who cannot have noticed the impact. Whether directly or indirectly it’s a lack of tax revenue that is at the heart of much of our political debate now, including that on austerity.

That’s also why tax is a One Nation issue. What the graph shows is something that’s undeniable, which is that the government now has a deficit. No one denies that this is an issue that must be addressed, but how it is addressed is now creating real difference on the subject of tax. That in turn highlights different attitudes towards this country and its people from different political parties.

The Conservatives have decided that the deficit must largely be cleared by austerity, which impacts the poorest hardest. Those tax rises they have imposed have also hit the poorest hardest: the increase in VAT to 20% is the surest sign of this. At the very same time the Conservatives have cut income tax for the richest in the UK from 50% to 45% and cut the tax rates on large companies (but not small ones) by more than 20% whilst they have also made it much easier for companies to shift their profits to tax havens.

The results have been all too obvious. At least in part because of the government’s tax policies the gap between rich and poor in the UK, whether measured in terms of income or wealth, has been getting much bigger whilst stories about corporate tax scandals are now an almost daily occurrence.

This need not be the case. A party committed to One Nation, working together to build widespread prosperity, would not say it has to cut taxes for the rich because it could not beat their tax abuse; it would set out as Labour did to close the loopholes in our laws to make sure everyone pays what is expected of them.

Likewise, a party committed to One Nation would not say to multinational companies, as the Conservatives have done, that we will from now one leave all the profits they earn outside the UK out of tax and then at the same time open the door for them to shift their profits to tax havens. It would, instead, as Labour did defend our right to tax all UK profits here, in this country.

And nor would Labour have increased VAT, hitting the poorest, and even those who don’t pay income tax, especially hard. It has said it would instead, as Labour did in 2008, have reduced VAT if recession had returned, as happened in 2011.

There is good reason for all this on Labour’s part. A One Nation tax policy recognises that tax is not just about raising money for the government, as important as that is. It is also about making sure that tax is paid by those who can best afford to pay it, which is inevitably the best off in society. And a One Nation tax policy also require that those companies who are making the most in this country should be made to pay the government for that privilege rather than paying lawyers and accountants to find ways to get round tax law, so avoiding their obligations to society as well as their tax bill.

All that’s because a One Nation tax policy is built on three ideas.

The first is that the law is upheld so that everyone, whatever their wealth, pays the right amount of tax in the right place (which means the UK) at the right time if the law requires it.

Second, it means that those with the greatest capacity to pay must pay most, not just absolutely but as a proportion of their income or wealth.

And last, tax law must reflect social policy so that if Labour thinks that markets can sometimes deliver injustice, including too little reward for some and excess reward for others, then it must be willing to change that situation to create a fairer, more equal but also more vibrant economy with opportunity for all by use of tax policy.

Tax can do that for One Nation, working together. Nothing else can do it as well. Which is why fair tax has to be at the heart of Labour’s policy for a One Nation future.

Richard Murphy is an adviser to the Tax Justice Network and the TUC on taxation and economic issues.

This piece forms part of Jon Cruddas’s Guest Edit of LabourList

More from LabourList

‘Dunblane’s legacy: how grief, courage and a community’s campaign helped ban handguns’

‘While the right panics on Iran, Britain needs clean power, not chaos’

Delivering in Government: your weekly round up of good news Labour stories