Last weekend saw four fantastic Labour women selected to fight for parliamentary seats at the next General Election. Since 1997, Labour has led the drive to see more women in Parliament, creating a politics that looks and sounds more like the country it represents. What was true under Tony Blair and Gordon Brown is still true under Ed Miliband and his words about creating a better politics are backed by more women entering representative politics through our party.

Yet it wasn’t always so promising.

In 1888, the relationship between women and politics was radically different. Despite often being subject to horrendous conditions – from the home to the workplace – women were effectively excluded from public life.

The one hope most ordinary women had was their own ability to organise. And on this very day 125 years ago, a small group of women got organised and changed the face of industrial and political history.

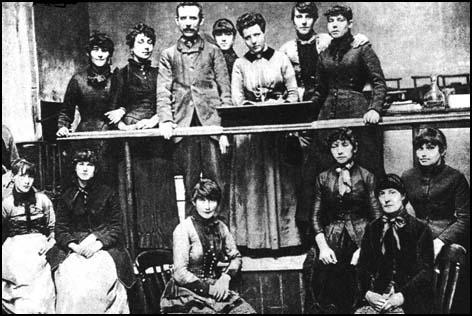

It started in an unremarkable match factory in London. While the profits of the Bryant & May match-making company grew, the wages of its largely female factory workforce shrank. The women who worked in the factory (somewhat condescendingly known as “the Matchgirls), were routinely assaulted by foremen, sometimes sexually. And “Phossy Jaw”, a disease that led to the slow rotting away of the jaw, caused by ingesting white phosphorous from the matches, was a constant threat.

Despite the appalling conditions, the women still maintained a spirit of community and camaraderie on the factory floor. They were well known in the local community as colourful characters who wore bright feathers in their hats. But it turned out they had a fuse.

With the help of Annie Besant, a middle-class journalist, the workers started to publicise stories of their experiences and treatment. The factory owner, annoyed at the negative exposure, insisted the women sign a declaration saying that the stories were false. When they refused, the owner sacked one of the women in an attempt to make an example and quell the stirring rebellion.

It was one humiliation too far.

The women, buoyed by growing momentum, downed tools and went on strike. The factory fell idle. The owner, sensing his hand was forced, offered to reinstate the sacked worker. But it was too late.

Despite lacking support from any trade union, the women organised to elect a Strike Committee and lay out further demands.

Now they had the power, and their power had been recognised. They demanded, along with the reinstatement of their fellow worker, an end to unfair fines, along with the provision of a dining hall so that they wouldn’t have to eat at their work stations and risk contracting the dreaded “Phossy Jaw”.

After a few unsuccessful negotiations, a lot of media coverage, and with steadfast determination to win, the owner caved. Every one of the women’s demands were accepted and the strike ended. Through this victory, the women created the largest union of female workers in the country and helped to lay the foundations upon which our Labour Movement was built.

Today, it is worth commemorating that victory. But it is also worth learning from it.

Just like “the Matchgirls”, women today need to act in order to effect collective change. To change a society that still has too few female political representatives, an economy that still pays women less than men and a world that still stands by as women are used as weapons of war. This means getting organised.

Like the refugee women from across London, brought together by Women for Refugee Women and co-trained by Movement for Change to found London’s first ever women’s refugee forum.

Or the group of young mums in Bonymaen, Swansea, getting organised to end the harassment they face daily from doorstep lenders, as part of the national campaign that is fighting to cap the cost of credit.

Or the team of activists in Brixton who, after speaking to women across the area, decided it was time to take action on the insecurity that women felt at night. They organised to change the way clubs treat harassment in their venues and to change the conditions under which the Council hands out licences to bars and clubs.

Today, let’s remember the bright feathers of the women from Bryant & May. May their memory be a call to action, for the next generation of Labour leaders.

Kathryn Perera is the Chief Executive of Movement for Change

More from LabourList

Starmer the class warrior? PM pivots focus towards ‘class divide’

FBU launches ballot on strike action in Oxfordshire over cuts to fire service

Lord Doyle has whip suspended over links to sex offender