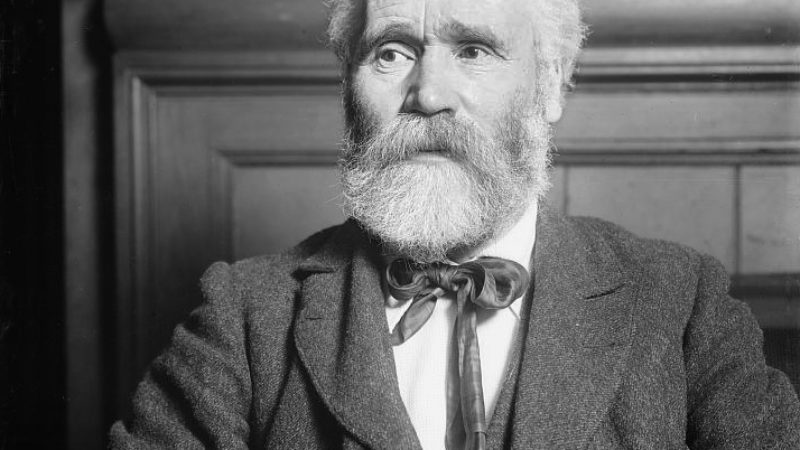

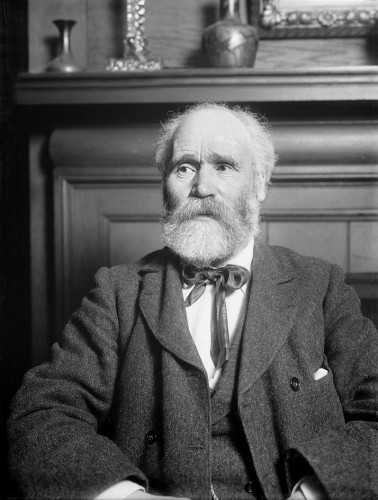

Writing in 1895, Keir Hardie protested that the Liberal Party of the era was too obsessed with electoral reform. Though he said that universal suffrage was a cause “dear to the heart” of the Labour movement, he feared that its immediate implementation would merely depose the aristocrat in favour of the plutocrat. For Hardie, it would take decades of social reform before it would be appropriate to widen the franchise. He saw the Labour movement’s role as being to facilitate the empowerment and education of working people so that they could one day take up their rightful place as active citizens in an equitable, democratic polity.

Though much has changed in the 119 years since Hardie outlined his pragmatic objections to an enlarged franchise, in many ways much has not. Our institutions remain fundamentally unaltered since those days; the establishment of universal suffrage and other democratic reforms did not create a new political process, but sought to bring the mass electorate into a democratic system never designed to represent them.

The rise of UKIP is being heralded in the media and by the political class as a symptom of broken politics in this country; a kind of 21st century equivalent to the peasantry revolting against the gentry. We are told UKIP voters are angry and discontented because politicians have become remote, distant and out of touch. Within our party, this has prompted a debate on what we do about policy: should we tack to the right on immigration for instance, or perhaps we should consider offering a more traditionally socialist economic programme?

This is perhaps an important debate worth having but one that rather misses the point. It is not just that our politics is broken; rather, our democracy itself is sick.

As several commentators and political scientists have observed, UKIP’s rise is largely attributable to the fact that it is breaking out of its traditional ex-Tory base and appealing on a significant scale to millions of disaffected, marginalised working and lower middle-class people. Yet we also see that there is a fundamental disconnect between what most UKIP voters think they are voting for and what they are actually voting for.

As The Independent humorously noted last year, research has demonstrated that the “British public are wrong about nearly everything”. According to Ipsos-MORI, people perceive that the recent immigrant population is more than double its actual size; one in four think foreign aid is one of the most expensive parts of the government’s budget. Parties like UKIP exploit this to further their own regressive ideological interests. They focus on misconceptions about issues like immigration to justify or conceal their agenda for the wholesale decimation of public services and welfare.

Policy shifts may hold UKIP back but they will not solve the underlying problem. To fight right-wing political insurgency, Labour needs to recall our own heritage as a radical insurgent party of the left – a party that exists to challenge, not uphold, traditional politics. Labour will need to find a way to modernise our democratic process in such a way that will in the long term create an informed, politically educated and socially engaged electorate. It is not enough to have a democratic process that is there for those who want it; Labour needs to finish the task it began over a century ago find a way to build a new democratic polity that is aggressively inclusive, empowering and accessible to all.

To do so may require reforms that are politically inconvenient in the immediate term. But if we do not take action, then there will come a day when UKIP or a party like it may well win government – and if that day comes, then all we have achieved in government may well be lost for a generation or more.

More from LabourList

‘Tackling poverty should be the legacy of Keir Starmer’s government’

‘The High Court judgment brings more uncertainty for the trans community’

‘There are good and bad businesses. Labour needs to be able to explain the difference’