Not only is the coming election shaping up to be one of the most difficult to predict, but it is also likely to be the first in which devolution is an issue across the whole of the UK. Last week the Tories put forward their solution to the West Lothian Question – English votes for English laws – and you can be sure that they will be pushing this policy hard over the next few months in the hope of winning votes from UKIP.

Labour’s promise of a constitutional convention to look at this issue is simply not going to resonate on the doorstep in the same way. Gordon Brown’s intervention in the Scottish referendum debate shows that when people are offered a mechanism for genuine change and a timetable for its delivery, they will come out and vote.

By making lukewarm noises about devolution, Labour is in danger of ceding the devolution debate to the right, while at the same time allowing the LibDems, the SNP and the Greens to pick up votes with demands for reform at Westminster. If it hopes to make the running on this issue, the party needs to come up with a comprehensive plan for UK wide devolution that can be implemented in time for the 2020 election.

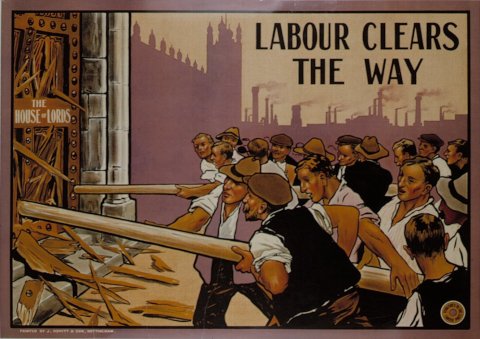

Labour has a proud tradition of devolving power away from Westminster and the framework of further reform can already be seen in Ed Miliband’s commitment to scrap the House of Lords and create an elected Senate of Nations and Regions. It’s a genuinely radical idea that would both inspire our activists and give the party ownership of the devolution debate.

The only thing that stopped this policy announcement grabbing the headlines it deserved in October was the lack of a clear explanation of the mechanism involved in creating such a second chamber and a firm commitment to a timetable for delivery.

Over the past decade, we’ve witnessed a loss of faith in participatory democracy. Many voters feel that their voice is not heard in Westminster, an attitude underlined by the fact that the vast majority of us live in safe seats where one party remains in power for generations. What’s the point of bothering to go down to the polling station if you know your vote is going to end up in the bin?

Labour could directly address this issue by distributing the seats in the newly created Senate of Nations and Regions in direct proportion to all of the votes cast in the general election. This form of indirect election – known as the secondary mandate system – would create an upper house with much greater legitimacy than the House of Lords, yet its members would not be so legitimate as to challenge the primacy of the Commons.

On election night, all votes cast would be tallied on a regional level and members of the senate would be elected from party lists. 25 members from each nation and region would produce a senate of 300, a 65% reduction on the current membership of the Lords.

If this mechanism were coupled with a firm commitment to implementation by the 2020 election, I believe that such a policy would allow activists to engage on the doorstep with voters of all parties and none, giving them the chance to gain a hearing for Labour’s other important policies.

Yes the economy will be the biggest issue at the next election, but we can’t hope to have an economy that works for everyone unless we first create a democracy that works for everyone.

The lack of trust between the people and their representatives in Westminster is going to be the elephant in the room during the election campaign. This policy goes to the heart of that issue by allowing Labour to say, to supporters of all parties, we trust you to use your vote wisely – trust us to make that vote count by 2020.

By utilising the mechanism of the secondary mandate, coupled with a timetable for its introduction, Labour can take control of the devolution agenda once again and use it to start the process of rebuilding trust.

More from LabourList

‘Be real Labour’: Unite cuts Labour affiliation fee by 40% and hits out at government

The Iran war underlines the need for Labour’s net zero commitment

‘Labour’s next big win is children’s health – but only if it acts now’