Sometimes I wonder at how well Labour is doing despite everything. With growing inequality and despair even among Tories about tiny elites exercising extraordinary power, these should fertile times for left politics. But, ever since the mid-1970s, the Labour party has been unable to craft a clear enough sense of what it is about. Our last truly big theme was Harold Wilson’s white heat of technology the decade before that. There was very little new about new Labour. All Tony Blair did was turn the Labour Party back away from the madness of the early 1980s back to its post-war tradition of social democratic centralism, ironically enough bringing it back into line with the old politics of Labour’s first real moderniser and one-time Minister of Technology, Tony Benn. Blair’s look, all white shirts and rolled sleeves, was straight out of the 1960s. The only novelty was the language of community and stakeholder participation. But signs New Labour would take seriously pressure for greater democracy and accountability were quickly killed in favour of thoroughly modernising technocratic centralism. Blair was out of date even in 1997. And the year Blair was elected leader is now closer to 1974 than our present time.

Ever since Wilson’s rhetoric of technological revolution, nothing has held the Labour movement together other than membership of a common cluster of institutions and a desire to get a Labour government elected. In the Labour Party you can be anti-business and pro-business, fiscally prudent and fiscally profligate, socially conservative and socially radical, for disarmament and for more war, localist, centralist and everything in between. During Labour meetings, I constantly ask myself in surprise, “you can be in the Labour part and think that”. As leader, Ed Miliband’s job was to craft from the shattered pieces of our movement a clear story about what the Labour party was about, to create a sense of what Labour is for which could be communicated on the doorstep. Early signs after 2010 were promising, but the election gets closer, it’s clear he hasn’t done the job. That’s why I’m pessimistic about the outcome in May.

Contrast the state of Labour with the Conservative Party. Their message has been roughly the same since the party was founded in the 1840s. The Tories are there to guarantee order and stability in changing times. They believe in property, decency, hierarchy, a (usually) moderate kind of nationalism and the existing social order. They are good, they tell us, in a crisis. They are brilliant at reinventing themselves and taking on-board enough charge to keep the social hierarchy in place. Their emphasis on stability makes them most easily undone by the appearance of fumbling incompetence – 1964 and 1997. But it also allows them to speak in a way that connects with our everyday lives; security starts at home, and don’t let Labour endanger it they say.

But hold on a minute, what about equality? Labour, surely, does have a core value, creating a more equal society. I’m not convinced. Yes, we all talk the language of equality, but it doesn’t offer a clear guide to what Labour’s about in the way order does for the Tories. Equality is hard to define. What numbers do we use? Do we mean equality of opportunity or outcome? Ultimately it ends up is a way of talking, in a technical and aggregate way about society, not about peoples’ lives. Of course we experience the benefits of equality. More equal income distribution has important consequences. But equality itself can only be measured by a statistician. It isn’t easily translated into feelings – and emotions not statistics win elections.

My argument is that without a sharp enough story about what Labour is for, we fall back on the language of moral outrage. Desperate to agree about something, we blame the Tories for planning the demise of cherished national institutions like the NHS, for privatisations, for cuts which we don’t ourselves rule out, for causing pain and suffering everywhere. As Douglas Alexander argued four years ago, ‘moral outrage is not enough’. Alexander argued then that is no good ‘to bombard the Tories with impassioned and aggressive attacks’ without creating public confidence in our own plans. Yet that is exactly what we, Alexander included, are doing now.

A campaign centred on moral outrage did well in 1987, when Neil Kinnock’s Labour Party saved itself from being pushed into third place by the SDP-Liberal Alliance with a beautifully crafted series of images. I still have posters of the red rose in the broken operating theatre. The slogan was ‘the country’s crying out for a change’, a phrase which has started to reappear in the speeches of leading politicians. The difference in 2014 is that we’re trying to win the support of a majority of electors.

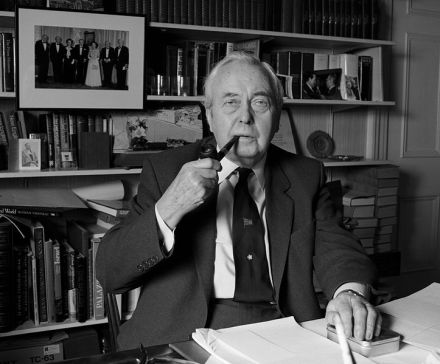

The problem of moral outrage – then as now – is that it has nothing to offer equivocal voters, the kind of people who aren’t sure whether to stick with what they know or switch. It demeans the choice of people who voted Tory in 2010 as not merely the wrong thing to do, but a moment of moral bankruptcy. It ends up as an internal language of self-justification, a way for those of us who truly care to feel good about ourselves. But when we need to reach out beyond our support base it makes Labour seem hysterical, partisan and sectional, in contrast to Conservatives claims to be neutral leaders of the nation. Labour only wins when it offers people reassurance (Wilson’s pipe, Blair’s… everything). At a time when there’s so much rage against big business, reassurance needn’t come at the expense of radicalism. But it doesn’t come with stridency. I think too few of Labour’s leaders get this, because they have been surrounded by Labour people – people who sometimes seem to share little but their own outrage – all their life.

As the German sociologist Max Weber argued, politics needs to be underscored with realistic passion. Politicians must take a stand and lead with rhetorical conviction. But they must do so responsibly, and follow through with concrete plans driven by a sense of proportion about what’s possible. Politics is about real causes. Our danger now is that Labour veers between dead policy speech and vapid moralising. When a government measure is criticised, I want to hear a clear and simple account of what we’ll do instead.

What this government is doing is enough to make us all angry. But rage is cheap, and leadership depends on a clear sense of how we will act collectively to remove its cause. Policy details don’t win elections; victory instead comes to politicians who have a clear approach, and can tell straightforward story about what they’d do in power. Those men and women seem in such short supply in the Labour Party now, not through their personal failings, but because serious conversation about what Labour is for has so long been absent. Whatever happens in May, we’ve got work to do to put our party and our movement back on track.

More from LabourList

‘As metro mayors gain power, Labour must tighten political accountability’

Letters to the Editor – week ending 22 February 2026

‘The coastal towns where young people have been left behind by Whitehall’