Last week I looked at the detail behind the General Election results to see what the lessons were for Labour in terms of differential performance by region or demographic group:

This week I wanted to take a more detailed look at the seats Labour needs to gain to form an overall majority.

This list comes with the caveat that assuming the boundary changes go through (with greater equalisation of electorate size and a reduction in the number of MPs to 600), there will be wholesale changes that will make the challenge even harder for Labour (e.g. Wales will lose a disproportionate number of seats because its current seats have fewer voters).

But, for now, this list gives us some the broad picture.

Here’s the whole list, courtesy of @AndyJSajs.

A Labour overall majority requires 94 gains and a swing of 8.7% i.e. overcoming seats with Tory majorities of up to 10,000. By contrast, at this last General Election a Labour overall majority would have required only 68 gains and a swing of 6.5%.

The list goes beyond 94 gains to 114 to show the next 10 seats that would give Labour some kind of working majority (and to allow for some misses earlier down the list).

It would be difficult for Labour to be able to target as many as 114 seats – we were spread too thin going for 106 key seats this time round – but the ones we do go after will need to be from this list unless there is a massive turnaround and collapse in SNP support in Scotland.

Taking these 114 seats as a whole, let’s look first at who holds them. There are 3 remaining Lib Dem seats (Leeds NW, Sheffield Hallam, Southport), as we already cleared up almost all of those; the single Green seat in Brighton Pavilion, 16 SNP seats, and two Plaid Cymru ones. So the vast majority, 92, are seats Labour has to gain from the Tories. With a couple of exceptions such as Watford, there is virtually no Lib Dem vote left to squeeze, so the only route to victory is to get voters to switch in these seats direct from the Tories or to get a disproportionate share of the UKIP vote, which the Tories will also be squeezing.

In five of the seats Labour starts in third place.

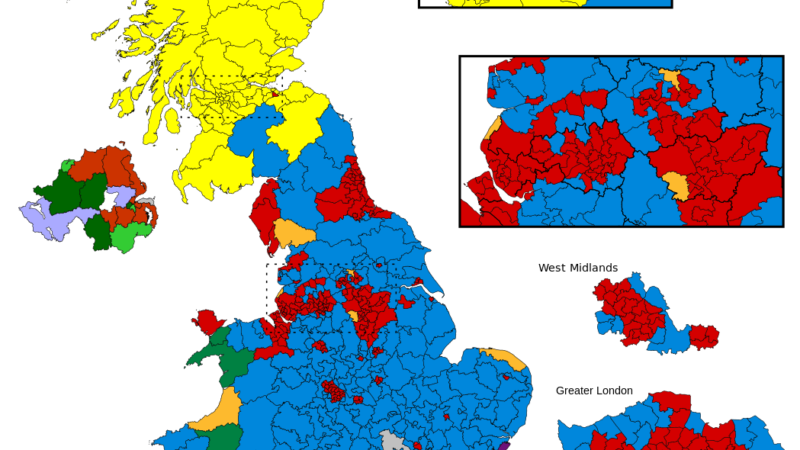

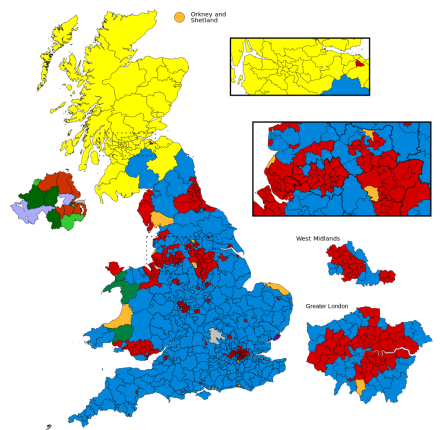

Where they are?

Scotland 16

South East 14

North West 13

West Midlands 12

East 11

East Midlands 11

Yorkshire & Humber 10

Wales 10

London 8

South West 8

North East 1

The first thing to note is that we will need an appeal that is truly national as the spread of marginal seats is far more even around the regions than in previous elections (a typical pattern in the 1980s and 1990s would have seen a greater clustering of target seats in London, the West Midlands and the North West) .

But within this pattern we need an ability to make the most widespread gains simultaneously in some of the most ideologically leftwing terrain (Scotland, Wales) and the most ideologically rightwing regions (South East, Eastern), as well as in the traditional swing regions (North West, East Midlands, West Midlands).

London is suddenly less significant because we have already done so well there this time, Wales and Scotland much more because we did so badly there.

How much work has been done in these seats?

73 of the 114 seats were in the list of 106 Key Seats targeted in 2015 so presumably start from a reasonable level of organisation and canvassing data.

However, the remaining 41 were not, and on the whole (with some notable exceptions like Southampton Itchen and Sheffield Hallam) are likely to be starting from a lower baseline, consisting of:

- 8 seats lost by Labour to the Tories

- 16 seats lost by Labour to the SNP

- 17 seats in England and Wales that had not been considered worth targeting in 2015 but are now part of the battlefield as they are either trending towards Labour or because we did so badly in Scotland

The first two categories will be slightly less winnable than they look on paper as they will benefit from a “double incumbency” factor – the boost first term MPs get because of the profile they get and casework they do at the same time that these advantages are removed from their opponents.

The third category includes seats from the Blair landslides that were lost in 2005 (e.g. Enfield Southgate, Gravesham, Reading East, Shipley, Shrewsbury & Atcham), and seats that have never been won by Labour (Canterbury, Chingford & Woodford Green, Chipping Barnet, Portsmouth South, Sheffield Hallam, Southport).

It’s possible to see a rough breakdown by type of seat too:

Midlands towns (each small enough to cover a maximum of two seats; NB manufacturing is still economically important in many of these): 22

Coastal towns (of which five are in Wales and three are economically dependent on the Navy, many of them have serious structural economic problems): 20

Pennine towns (each small enough to cover a maximum of two seats; NB there are particularly high levels of owner-occupation in these seats for historic reasons): 13

Southern towns (each small enough to cover a maximum of two seats; NB several of these have high levels of manufacturing and hi-tech industry): 10

Previously safe-Labour Scottish Central Belt seats: 8

London outer suburbs (of which 4 have very large Jewish communities): 7

New Towns: 6

Scottish seats with a traditional high vote for other unionist parties: 6

Three-way Kent & Essex fights with UKIP: 3

Traditional Lab vs SNP marginals: 2

That only leaves a scattering of other seats that don’t fall into these categories, for instance there is only one inner London target seat (Battersea) and only four others in big cities as Labour is already so dominant in urban areas.

The predominance of middle-sized towns as marginals (the kind of town that has one or at most two parliamentary seats) is a standard feature of the way the First-Past-the-Post system works in the UK: if a town is the right size to be self-contained in a single constituency it is likely to have the mixture of both middle and working class districts and voters that will make it follow the national swing reasonably closely, whereas bigger towns can often be divided into, for example, a Tory seat and a couple of Labour ones.

Anyone with a cursory knowledge of Chipping Barnet or Canterbury (where I grew up) will know that Labour will have to make some dramatic changes if it is going to entice the type of seats towards the end of the list back into its column. My sense though is that in doing so we may also bring back into play a swathe of seats which no longer even appear in this list but were, until as recently as 2010, Labour-held. What appeals to the listed Canterbury, Dover, Gravesham and Thanet South is likely to also work in the other off-the-list five former Kent Labour seats, and what works in Portsmouth South is likely to work in the previously more winnable Portsmouth North. Whether we can do this at the same time as winning back the 24 Scottish seats that were Labour until 7th May and are now not even in this rather long target list is an even greater strategic dilemma.

More from LabourList

Letters to the Editor – week ending 15th February 2026

‘Labour council candidates – it’s tough, but all is not lost’

‘Labour won’t stop the far right by changing leaders — only by proving what the left can deliver’