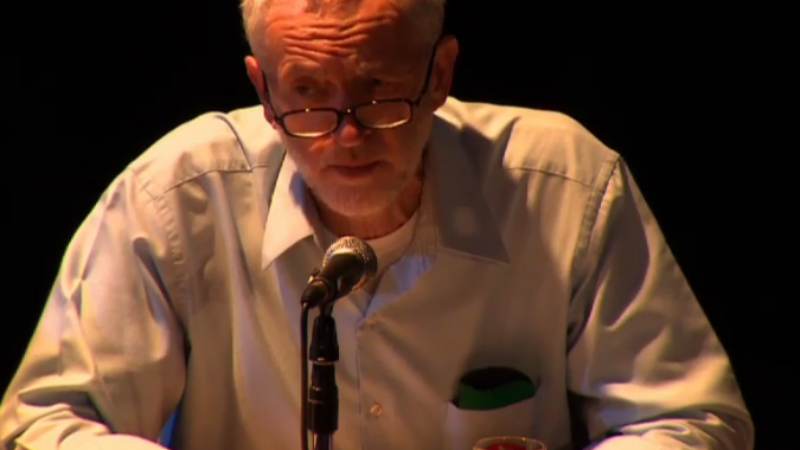

“Can Jeremy Corbyn actually win?”

It’s the question I’m asked with increasing frequency these days. “No” is my honest answer. But then, no, I didn’t think Corbyn would make the ballot, and no, I didn’t think the Tories would win a majority. So: no, don’t take my word for it.

One factor that appears to be giving the Corbyn campaign momentum is their social media presence. However, the word “appears” does an important job in that sentence: if politics could be accurately tracked by Facebook likes, September would have seen Scotland choose to leave the UK, and Britain First would have romped to a landslide victory in May.

Corbyn has not, at any point, looked like he is particularly passionate about becoming Labour leader. The reason he is there, by his own argument, is to widen the debate.

Also, his candidacy was announced late, following failed attempts by the left to convince Ian Lavery, Jon Trickett, and even Lisa Nandy to run. Corbyn ended up putting his name forward largely down to the fact he wanted someone on the left to vote for. Considering it is this wing of the party that rally to the cry of “Don’t mourn, organise!” after every defeat, they found it remarkably difficult to get their act together in the post-election vacuum.

Age and experience is part of the problem for Labour’s parliamentary left. While they had an impressive new intake at this election (Louise Haigh, Cat Smith and Clive Lewis to name a few), it would be a big ask for any of them to go for the top job straight away. Then there are those who have been around a while: Corbyn, Trickett, McDonnell, Meacher and Skinner being the most obvious.

But there are very few in between. Most notable of the 2010 intake are 53 year old Lavery, and the more moderate Nandy, who is even younger than Chuka Umunna. Both are backing Andy Burnham.

Of all those names, only Jon Trickett and Michael Meacher have Shadow Cabinet experience.

If Jeremy Corbyn fights the next election as Labour leader, he would go into it hoping to become the oldest person to become British prime minister for the first time. This is no bad things in itself – people are staying healthier much longer, and the bicycling Islington MP seems in perfectly fit.

However, whether he wants to be prime minister is another matter. A lot can be achieved in five years as Labour leader, and it could be that it is not Corbyn’s plan to lead the party into May 2020. What, then, would happen if Jeremy Corbyn won?

While it seems clear he would immediately set out Labour’s opposition to almost all spending cuts (I reckon he might find some in the defence budget), Corbyn would probably give back a lot of policy power back to conference delegates. We could potentially see the return of PLP elections for Shadow Cabinet places, but as he would struggle to fill the roles with his MP supporters anyway, this would not hurt him particularly. He would, presumably, be generous with junior frontbench roles to those on the left though.

Here’s the important bit: he would give himself a get-out clause. At the Newsnight hustings last month, he pledged to introduce a system where the leader would need to be voted for by members every year. This would provide Corbyn an annual opportunity to stand aside with minimum fuss. If he were to promote some of the PLP left to high-profile positions, and bring through a flurry of party reforms, handing greater power to conference and trade union delegates, he could be in a good position to stand down in 2018 with someone willing to continue his agenda ready to take over.

More from LabourList

Letters to the Editor – week ending 15th February 2026

‘Labour council candidates – it’s tough, but all is not lost’

‘Labour won’t stop the far right by changing leaders — only by proving what the left can deliver’