I suppose the first thing to say about me is that I’m not a Labour Party insider. I’m not a party member and am not offering any partisan insight. I’m best known as a psephologist plying my trade as a pundit in the media and as an academic writing about most aspects of party politics and electoral engagement of hard to reach groups.

The point of this post and Amina Lone’s from earlier in the week is to offer a dual insight, Amina from the frontline relaying experience of everyday politics, knocking on doors and wearing away the shoe leather, and me from a more distant viewpoint trying to analyse where we are in terms of party politics post the 2015 General Election. Our work together will culminate in a call for action, and particularly with a campaign to broaden both the number of voters who actually determine the outcome of Westminster elections, and the range of policies that are offered to them, but for now it’s right to perform a basic stocktake of Labour’s position.

First things first; Labour supporters must face up to the reality of the defeat. Much will be written about the future direction of the party, and as Amina Lone says the ascription of factional labels to everyone involved in the future direction of the party is not always helpful. That said, it is clear that Labour benefitted electorally post-1992 after the Conservatives pulled off a largely unexpected but decisive general election victory. Labour’s leadership had already embarked on what academics at the time had come to call a ‘superclass strategy’ since it was clear to party strategists after 1983 that that section of the electorate on which it had come to rely for its support was demographically insufficient to deliver a parliamentary majority. A change in electoral outlook started by Neil Kinnock, accelerated under John Smith and taken into another gear entirely by Tony Blair took Labour in search of the median voter, and geographically to the places where votes could count the most in forthcoming elections.

Under the leadership of Tony Blair, it became fashionable to talk of a ‘big tent strategy’ driving Labour’s electoral machine. Decisive national victories in 1997 and 2001 might have left many to conclude that the Big Tent was necessary but was it actually sufficient for the party’s future? In fact as early as 1997 it was clear that Labour was actually losing ground in some of its safest seats. This was most obvious in what some called the new sources of abstentionism, as turnout among traditional Labour voters in party strongholds began to decline sharply. By 2001, the fall in turnout to 59% had become the major story in British politics but most of the talk of the democratic deficit missed the point that it was Labour absenteeism that was the most remarkable feature of falling turnout. Of the 100 seats with the lowest turnout in 2001, 96 returned Labour MPs – usually with very comfortable margins. in truth the Big Tent may have not have actually expanded, the canvass was just conveniently moved to a different part of the field.

The point of returning to this after 2015 is that Labour still has difficulty mobilising some of the party’s natural supporters and, as the Conservatives have recovered in many places that turned Labour in 1997, the party has not found it as easy to convert latent support in its heartlands as it might have imagined. Put simply once voters fall into non-voting, they often stay there. Recent recent from the BES team has shown that Labour had a comfortable lead among those voters who were extremely unlikely to actually vote, the Tories enjoyed a 10% lead among those voters who identified themselves as certain to vote.

Moreover, those voters who flirted with other parties when Labour were in the ascendency might not come back. The BNP threat to Labour’s core vote may have been seen off, but the threat of UKIP to Labour in many seats was almost wilfully ignored by a Pollyanna electoral machine which noticed the good news (UKIP’s potential to be a British tea Party dragging the Conservative to the right and possibly weakening their electoral support) and failed to spot the dark clouds (Ukip’s ability to replay some of its campaign themes from the golf clubs into the working men’s clubs) especially if the claim that Labour had for too long taken the disaffected for granted seemed credible). Once credible alternatives to Labour are established the party has to work extremely hard to prevent the movement away from the party.

Nowhere was this clearer in 2015 than in Scotland but Labour should not have been so blindsided by the march of the SNP. Of course the Independence Referendum played a vital part (and the negative themes of the better together campaign may have had a longer term impact on Scottish opinion than was anticipated) but the SNP did not suddenly turn on Scottish Labour in 2014. The signs of atrophing Labour spport were evident in the 2011, and even 2007, Scottish parliament elections. The SNP were by 2015 the credible alternative to Labour and Labour’s performance in Scotland in 2015 was all the more shocking as the party seemed powerless to stop thousands of voters decoupling from the nation’s dominant political force.

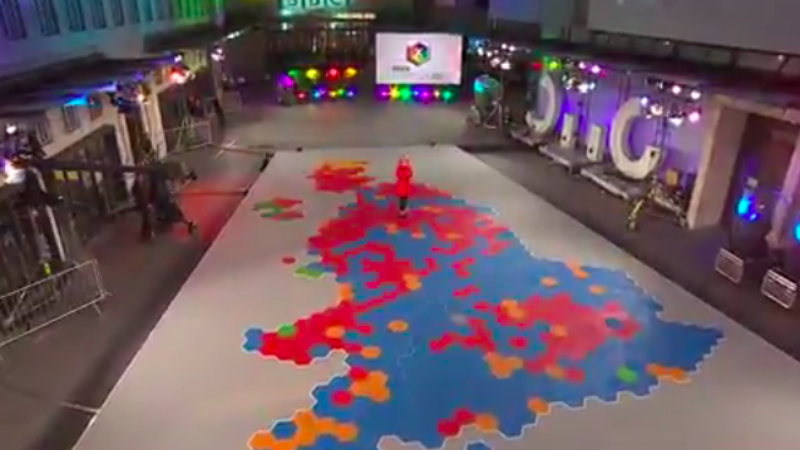

The Pollyanna Tendency persists. Labour supporters often point to the party’s improvement on its standing in 2010. I’ve also been frequently told that Labour received more english votes in 2015 than it did in 2005. these facts are true; but not helpful. Labour’s performance should have improved from 2010 – it’s remarkable that it did not improve more, while the use of 2005 – the least proportionate of all election results – is tantamount to sophistry. Labour received 8.04m votes in England in 2005, and 8.09m a decade later. Even if we ignore the increase in turnout which makes that improvement meaningless (Labour’s share of the vote fell by 3.8%) the performance of the Conservatives is decisive and the electoral geography of Labour’s vote is brutal. The Tories, who were already beating Labour in the popular vote in England in 2005 (but winning 92 fewer seats) improved their vote share by over 5% and put on more than 2.3m votes. While Labour lost 80 English constituencies between 2005 and 2015, the Conservatives won 125 more seats.

Labour’s best result came in London and cities like Manchester but do these actually represent a blueprint for recovery or merely highlight the difference between living in the metropolis and elsewhere? After all you don’t have to travel very far outside these cities to find places that Labour felt it should have won in 2015 but didn’t. Furthermore the importance for Labour of the collapse of the LibDem vote in the south of England seems to have been missed by many in the party that now suddenly finds itself fighting a Conservative party boosted by more than a score of victories from their erstwhile coalition partners in seats where Labour have little hope of winning.

The bad news is there is very little good news. According to Election Surveys, Labour does retain as many partisans, solid supporters, as the Conservatives but that just seems to throw the party’s inability to convert the less attached into stark releif. Moreover, this is an incredibly dangerous place for the Labour Party to be right now. The most compelling comparison is to the Conservatives of 2001. An electorate of the Conservative party choosing between leadership contenders choose decisively the one that seemed the most like them and made the true believers feel best about being Conservative. The choice of Iain Duncan Smith only made sense from this perspective; but at the very moment when the Conservatives needed to think about their appeal outside those that had stuck with the party in dark times it was a disaster. It will be interesting to see how Labour members react in their own version of 2001.

Andrew Russell is a Professor of Politics at the University of Manchester

More from LabourList

‘Tackling poverty should be the legacy of Keir Starmer’s government’

‘The High Court judgment brings more uncertainty for the trans community’

‘There are good and bad businesses. Labour needs to be able to explain the difference’