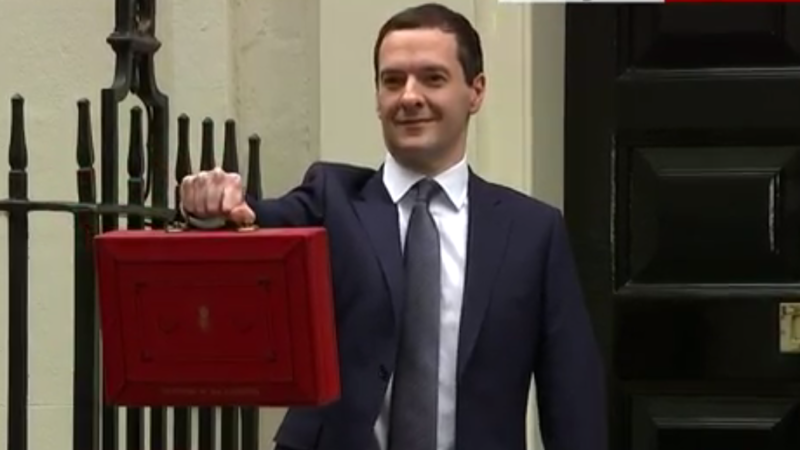

I have been worried about the impact of George Osborne’s fiscal charter since it was floated last summer, which is why as a member of the Treasury Select Committee I asked questions of the economists who came to give evidence last July.

We found no one, not even the Governor of the Bank of England, who would endorse George Osborne’s latest proposal. This was not just criticism from left wing economists. The Thatcherite professor who now runs the Institute for Economic Affairs, described it as a “very, very, very bad choice”. It is because no serious economist supports it that I believe this is a political gimmick by George Osborne. He wants to pose as fiscally austere irrespective of the consequences for growth and jobs.

A permanent government surplus would take money out of the economy, raising indebtedness in the household and business sector. Personal indebtedness is already running at 145% of disposable household income, a total of £1.7trillion and there is a clear case for pulling this back. The economists also said it was too clunky to enable the government to stabilise the economy when need be. In other words, this is a proposal to return to pre-Keynesian economics.

A really big weakness in George Osborne’s proposal is that he is saying there should be a permanent budget surplus, not just for current spending but for capital. No one thinks it is wise to max out the credit card to pay for the weekly grocery bill, but just as families have a mortgage to pay for their home, so it makes sense to borrow for the infrastructure – like broadband, transport, scientific facilities for universities – which will increase our economic productivity and growth.

When he spoke at Party conference, John McDonnell was quite explicit about the need to invest for growth. At that stage, the government had not published the final version of their fiscal charter or set out the parliamentary process they wanted to follow, so it was assumed that we would be able to amend the fiscal charter in Parliament. George Osborne arrogantly decided on Monday to give the House of Commons a take-it-or-leave-it deal. The Parliamentary process he has chosen to follow means there is no scope to amend the charter. Furthermore, we will only get 90 minutes for a debate on this really fundamental long term economic policy framework.

None of this makes Labour deficit deniers. We want to get debt as a proportion of GDP down. George Osborne failed spectacularly in the last Parliament – the debt went up by £200bn. Tackling the deficit involves sensible management of the public finances, such as cutting housing benefit fraud by £1bn and not giving the richest 60,000 families a further inheritance tax cut. It also means strengthening the economy’s capacity to grow, and that is why investments in infrastructure to modernise the British economy are so important.

Let us look at this historically – in 1948 national debt was 217% of GDP. In only eight years between 1955 and 2015 has the government run a surplus (incidentally, these were mainly in years when Labour was in power).

And this was because the – perfectly sensible – object of cutting the debt-to-GDP ratio was pursued largely through pursuing growth. I believe that was then, and would now, be a better strategy.

More from LabourList

Starmer the class warrior? PM pivots focus towards ‘class divide’

FBU launches ballot on strike action in Oxfordshire over cuts to fire service

Lord Doyle has whip suspended over links to sex offender