It’s widely accepted that General Election activists constantly heard the refrain ‘Labour doesn’t stand for people like me anymore’ . The reasons remain controversial. Post-election analysis suggested that voters who spurned Labour rarely rejected particular policies, or were rejecting the idea that Labour was simply too left-wing per se. Instead it seems that fears about Labour’s economic competence were reinforced by the belief that Labour stood for foreigners, migrants, welfare claimants – “anybody but people like me”.

Recently research into the attitudes of Labour members sheds some intriguing new light on why Labour may seem somewhat apart from the lives of majority of voters. Conducted by Ian Warren of Election Data, the survey asked party members about their sense of national identity.

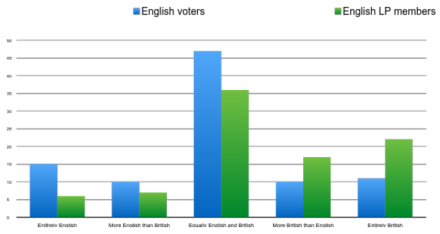

English members were asked to place themselves on a spectrum ranging from entirely British to entirely English. The same questions were put to 20,000 voters by last year’s British Election Study. Even though national identity data tends to vary from survey to survey, by comparing the two we can still get a pretty good idea of how the national identities reported by Labour members compared with those of the English public.

The result is striking. Labour members simply feel much more British and much less English than voters as a whole. Only 6 per cent of party members are ‘’entirely English’; less than half the 15 per cent of voters with the same identity.

In total, just 13 per cent of members are entirely or mostly English, while a quarter of voter prioritise their English identity. Nearly half the wider population are equally British and English, but only 36 per cent of Labour activists. While only 21 per cent of the public are either British or more British than English, 39 per cent of the party has these stronger British identities.

(Source: BES 2015, Ian Warren 2016)

Of course, it would be quite wrong to put all the distance between Labour and its potential voters down to national identity. There are many other issues that are at least equally potent. Yet national identity is, for many people, a deep and profound part of their being. Voters are quick to pick up a myriad clues (let alone tweets) that suggest the person they are talking to has a different view of their nation and identity.

At the very least, the identity gap sheds some light on why so many Labour members struggle to “get England” or the importance of responding to English sensibilities and addressing English issues explicitly and openly.

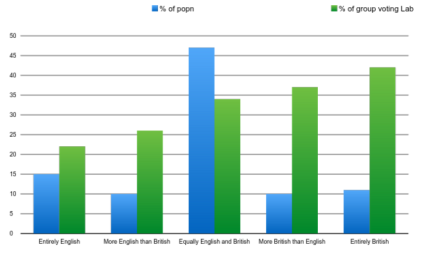

Does this matter? Electorally, Labour can hardly afford to write off voters with a strong sense of English identity, not least because some at least have helped to deliver Labour MPs and Labour majorities in the past. Labour did particularly badly amongst “English identifiers” last year, as the second chart (taken from the BES) shows. Labour received only 22 per cent of the votes of the “entirely English” rising to 42 per cent of the votes of the “entirely British”.

In doing better amongst the voters who feel more British, Labour’s members are reflecting those who currently vote Labour. The problem is that Labour can’t win in England without extending its political appeal to voters who feel their English identity strongly, In addition, the 2015 election showed, for the first time, the emergence of English voters who identified an “English interest” in the election that was distinct from the British interest. This was particularly marked amongst voters who feared the influence of the SNP on a weak Labour government.

This sense of an “English interest” is almost certainly shared much more widely than amongst those with a “English only” sense of identity. It reached into many different constituencies, across social class and ethnic identity. Addressing their concerns will also be important.

Political parties almost always have a membership that is rather different to the public as a whole. The challenge is to understand the gap and to find the ways to bridge them.

(Source: BES 2015)

The analysis of Ian Warren’s recent research has either celebrated a party united behind its leader, or worried about a party very distant from its potential voters. Both, of course, are true. How the Labour Party responds will be key to what happens next.

Prof John Denham is director of the Centre for English Politics and Identity at Winchester University and a former Labour MP.

More from LabourList

‘AI regulation is key to Labour’s climate credibility’

Ben Cooper column: ‘Labour needs to rediscover its own authentic populism’

‘Westminster rethought: a new purpose built site and a museum of democracy’