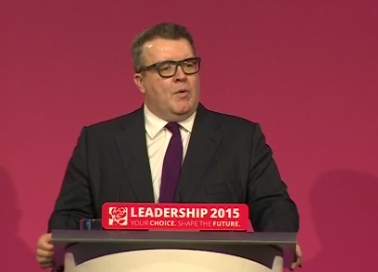

This is the speech on the “future economy” delivered by Tom Watson, Labour’s deputy leader, at the party’s Campaigning to Win event in Weymouth at the weekend.

I’m going to talk today about some of the big challenges we face in our future economy.

Firstly I should explain why Jeremy, Angela and me are actually here today, together.

We have been deeply heartened by the number of people who have become part of the movement in the South West. Our membership has more than doubled in the last 12 months, to over 30,000 members.

And many of our long standing members have been telling us we need to spend more time working with you in this part of the country, to work with you to organise communities and lead the discussion about how we build a fairer society.

And the three of us are totally committed to making your life in the Labour party more welcoming and engaging. And we’re also committed to making significant reforms to our digital platforms and tools to make it easier for you to campaign and debate, engage and organise.

So we’re trying out a few new tech ideas today. We’re live streaming this event to party members. I know for millions of people around the world, this does not seem like a revolutionary act. But for a century old political party, believe me, it is revolutionary. So welcome to you, if you are watching this event at home. Please bare with us, if some of the tech is a bit patchy today. We’re all on a steep learning curve.

But one thing I do know. Over the coming months, the Labour party will be more accessible not just on web platforms but on mobile phones and tablets.

To illustrate why this is our priority, let me ask you all to do something for me. If you have a smartphone please raise it in the air, or put your hand up if you have hidden it away – that’s a lot of smartphones right?

And isn’t it quite something that every one of you hold more computer power in your hands, in that phone, than all of NASA had when it landed two men on the moon.

Think about that for a moment, a hand held piece of kit that we use to check our emails, talk to our friends and families, listen to music and play games now has more computational power than all the machines used for guiding crafts though outer space some 49 years ago.

And we take that computing power for granted because we focus not on its power but on its simplicity. But that simplicity masks huge changes ahead.

We live in an era defined by technology and I believe that for all of us in this room we need to answer a profoundly important question

Do we make technology our ally or our enemy?

The answer is hugely important. Because the digital revolution has already transformed our world. But the automation revolution will turn it upside down.

In the next 25 years nearly everything will be automated. This will be the most profound change in industrial history. How we deal with its impact is down to all of us.

Last month we celebrated the centenary of the birth of Harold Wilson, our most electorally successful Prime Minister. Harold, defined the era of the jet age, forged in the white heat of technology.

Just over two decades ago, I remember applauding Tony Blair when at the Labour conference he told us that every school would be connected to the ‘Information Superhighway’. Today, my children’s generation no longer describe the Internet as ‘new technology’. It isn’t for them. It’s just the internet. The place where a ten year old can download WWE wrestling.

That combination of white heat engineering and massive computational power will make all our machines smarter. We are entering the second machine age, a new era of automation.

It sounds like science fiction. But it’s not the stuff of HG Wells, It’s happening in Tunbridge Wells.

I remember growing up in Kidderminster, in the west Midlands, marvelling that British Leyland had built robots that could assemble a car.

Today robots aren’t just making cars, robots are on the road driving them.

In his Budget last month, the Chancellor announced plans to allow driverless cars and lorries on UK roads.

By 2020, nearly every car manufacturer will be making driverless cars. I was telling Dennis Skinner about this and his response was to say he couldn’t imagine it happening. But then he added, people probably wouldn’t have been able to imagine horseless carriages in 1890.

By the way, whilst we’re on the Budget, John McDonnell has asked me to remind you of something. Can you believe that in the small print of the Budget George Osborne gave a £3,000 capital tax giveaway to 0.3 per cent of the population by trying to take £3,000 from hundreds of thousands of disable people? It’s further proof that Iain Duncan Smith was right for once when he said that Osborne was dividing not uniting society.

Anyway, back to the implications of driverless cars. They’re likely to lead to greater efficiency on our existing road networks, a reduction in road deaths, improvements to delivery times in the freight sector, increased competition in the rail sector. But also, massive displacement of transport jobs. The policy outputs are endless.

But it’s jobs I want us to focus on today.

Management consultants Deloitte say up to 11million UK jobs are highly likely to disappear when the machines of tomorrow carry out the work done by humans today.

Last year the Bank of America predicted that nearly half of all manufacturing jobs would be lost to automation, at a staggering saving of $9 trillion in labour costs.

And unlike the past, this wave of industrial change, will not just will not just affect the sectors traditionally held by skilled workers working with their hands.

The professions will be hit just as hard as traditional manufacturing jobs.

Richard and Daniel Susskind argue that it’s the traditional professions that will bear the immediate impact of the rise of automated systems.

Doctors, lawyers, pharmacists, engineers, academics and managers.

Why pay an accountant when computer software can do your tax return quickly and more cheaply?

The Financial Times recently reported that around 100,000 legal jobs will disappear as similar technology is introduced in the legal industry.

And to understand the scale of change to come, we must learn from our history.

When the industrial revolution unleashed the stunning power of capitalism, with the sheer productive force of industrialisation, society was changed forever.

The industrial revolution shaped our country – from the railways that brought people closer together.

To our great cities, with their town halls, libraries, galleries, museums and statues.

That wave of industrialisation created great wealth, great philanthropy, and great advances in the human condition.

But it also created huge upheaval, vast misery.

Child Labour. Infectious disease. Industrial injury. Fetid slums. Infant mortality. Children grew up without seeing the sun. You can still see it now in the streets of cities in Vietnam and Brazil.

It took an amalgam of municipal leadership, business philanthropy and the collective strength of workers to civilise the new economic landscape, shaped by technological advance.

Those forces were instrumental in the development of our trade unions and, at the turn of the century, our own party – created to represent the interests of working people.

As a country, we will need to forge a similar alliance to address some of the inequalities digitisation and automation is already creating.

We need government, workers, employers and enlightened entrepreneurs to work in partnership to ensure everyone gains from the benefits these changes will bring.

And that’s why despite these powerful forces baring down on us, and all the media attacks, I am optimistic for our party.

History shows that only the Labour party can bring people through these difficult times. Because only the Labour party believes in harnessing the power of the enabling state.

In the world of Sajid Javid and George Osborne, government is an impediment to market perfection. Their ideology dictates that the market alone must decide who wins and who loses.

That is not the Labour way. We are all here because we believe that work should be rewarded.

Unlike the Tories, we believe there is a distinction between the interests of Business and the interests of Capital.

Enterprise and hard work grow business that become employers, and contribute to the fabric of society in many ways, social and cultural, as well as through taxation.

Why we all joined the Labour party was because we think that government should work to support businesses and workers that create prosperity that can be shared by the many.

Capital is a necessary element in economic activity but slavish devotion to the re-creation of money for money’s sake will lead to a very dislocated and dysfunctional society when automated systems are doing much more of the work and creating much more wealth.

Our challenge in the next decades of automation will be to work out how we continue to grow our economy but ensure that the value created and time saved by automated systems is shared more fairly, and not used to further enrich an already wealthy and powerful elite.

When you are faced with such stark inequality, surely, we can’t leave the future economy to fate.

That’s what Sajid Javid wants to do with the steel industry. It’s not sensible. It’s not fair. It’s not in our country’s interest to do that.

Sajid Javid would like steel workers to think that he is powerless to act. He wraps his powerlessness up in and economic and political libertarianism, and hopes for the best.

His Tory colleagues eschew any role for government, reject any notion of an industrial strategy that might get a strategically vital industry through tough times.

Well Angela and John McDonnell have a different plan for the Steel industry.

And if we don’t act to shape our future economy, the graphs showing how much wealth is in the hands of so few will just continue to grow.

Just take a look at the tech companies.

Their success has been to concentrate greater wealth in fewer hands. And although the benefits they bring to consumers are enormous – the social dividend we receive from many of these firms is not as great as it should be.

When Instagram was sold to Facebook for $1 billion, it was reported that it only employed 13 people

Twitter has a global workforce of around 4,000 in 35 offices around the world – and a market value of $10bn.

Ford is worth $50bn. But it employs 200,000 people worldwide. It makes jobs as well as cars.

When Tony Blair made those predictions twenty years ago we couldn’t possible begin to imagine the impact of the information superhighway. Yet the golden age of the knowledge economy has not yielded all that it promised.

The effect of those big tech platforms has not just been to take out many jobs from the economy.

We have seen huge amounts of cash going on the balance sheets of the big tech companies, with very little investment in social infrastructure, education, skills and health.

Incidentally, if you want another argument for staying in the European Union then look at Google. When the European Commission took them on for abusing their dominant market position Google had to change what it did. When they’re pulling in $19 billion a quarter, even the finest UK Treasury lawyers would find it hard to take on the might of this transnational gorilla alone.

And as these digital industries dissect jobs into their task based elements, no wonder Hilary Clinton has warned of the threat of the ‘gig economy’

Just look at the Uber effect in London.

Uber have a technology platform that makes it simple to book a cab. It’s cheaper. But they have done this by delegating risks and driving down pay of drivers, who are poorly unionised and dependent on being allowed to remain on the Uber platform for their livelihoods.

Our colleagues in the trade union movement are taking steps to address that.

But the rise of the so-called ‘gig economy’ will create armies of new workers, and none of them will have the collective bargaining power that previous generations of workers fought so hard to win.

That has huge implications for our economy and our movement.

Uber, Facebook, Google and the other successful tech platforms have brought immense gains to the lives of millions of people, but they are part of an emerging ‘winner takes all’ economy.

And if you don’t believe me, take a look at the recent words of the most famous investment manager in the world, Warren Buffet.

“Productivity gains achieved in recent years have largely benefited the wealthy. [those] gains frequently cause upheaval. Both capital and labor pay a terrible price when innovation or new efficiencies upend their world’

In his recent letter to investors Mr Buffet says

“The solution…. is a variety of safety nets aimed at providing a decent life for those who are willing to work but find their specific talents judged of small value because of market forces.”

His point is that the wealthy can absorb the changes innovation brings but those at the bottom of the income scale rarely can. They need governments to help them.

And that why Scott Courtney is here today and will be talking to us about the magnificent campaign he is running in the States for a $15 minimum wage.

We already live in a world in which a greater proportion of wealth is held by a smaller number of people than at any time since the 1920s.

Automation will exacerbate that trend.

The forces of globalisation and automation are leaving our society’s Labour market looking increasing like an hour glass, with room at the top with those with existing wealth or access to capital and a widening glad base of lower paid jobs that cannot be automated. And a hollowing out in the middle, the jobs in retail or high street banking for example.

Do we really want a society of affluent leaders, struggling workers with little room in the middle and fewer chances for movement?

No wonder someone said to me that when we have our debate on the European referendum we should say to those people that are worried about immigration that it is not the Romanians taking your jobs you should fear, but the robots.

Before you think I’m being anti-technology, I’m not. What not to like about books, food to clothes delivered to your door. Or getting access to every piece of music and film ever recorded, available to stream into your living room?

Or our kids having the most comprehensive encyclopedia that’s ever existed at their fingertips.

When Harold Wilson gave a second educational chance to workers through the creation of the Open University, he wasn’t to know he would change the lives of millions.

Yet last year alone it is estimated that 35 million people signed up for one of the many Massive Online Open Courses available online.

It goes to show that if we make technology our ally, we can change the life chances of millions.

Aiko the robot receptionist shows how much our world is about to change.

Only our party, with our belief in partnership and the enabling state can forge a new industrial strategy, fit for the age of automation, fit for the epoch of drones, robots and automated systems.

We’re going to have to take head on the hour-glass economy, the future of work and the need to spread prosperity and not concentrate it in fewer hands.

And that’s why we’re here today. To shape the future.

Enjoy your day.

More from LabourList

‘Labour is being badly misled on housing’

Reeves bets on patience over populism

‘Energy efficiency changes must work for older private renters’