A Labour Party in civil war. Militancy. Entryism. Racially-motivated murders. Strikes in the public sector. The rise of nationalism. Phoney empire wars. Riots on the streets and a quasi para-military police force. Eighties Britain was a battleground for the very future of the Labour Party. There had been two humiliating electoral defeats. Britain’s first woman Prime Minister was triumphant. David Owen and Shirley Williams were being spoken of as the future of opposition politics; and Labour was in desperate need of modernisation. Enter Billy Bragg, Paul Weller and a brigade of chart-topping pop stars.

Red Wedge – a cultural force “for” but not “of” the Labour Party – entered Walworth Road in the summer of 1985 and set up next door to Peter Mandelson’s press office, offering national tours in return for party policy input.

Neil Kinnock welcomed the artist collective with open arms. In the two years since becoming party leader, he had made little progress in policy momentum. The miners’ strike of 1984-5 had consumed the party – but many still asked: where was Labour – and with a general election predicted for 1987, Kinnock needed all the help he could get. The fact he had once been honorary president of the Gene Vincent Fan Club impressed the hell out of radical songwriter Billy Bragg but it was not going to help overturn fierce Conservative majorities in the south of England.

Yet, despite protestations from within parliament of pop stars, and their wacky haircuts, parading down the corridors of Westminster, Red Wedge soon became a significant factor in the rebranding of the Labour party. Successive music and comedy tours had been hugely popular, and the joint Red Wedge-Labour Listens initiative and ground-breaking Day Events – reaching out to huge audiences of disenfranchised unregistered youth – had brought local, national and shadow cabinet MPs face-to-face with the realities of neglected communities across the length and breadth of the country. A generation on from punk rock, and its requisite anti-establishment posture, the marriage of pop and politics in the mid-eighties was at the vanguard of nursing disparate social and community groups neglected by the onslaught of Thatcherism.

By 1992, Red Wedge’s trust of Kinnock’s leadership had been vindicated within the papers drawn up for an anticipated electoral victory; expressly the inclusion of a minister for arts; gay rights firmly on the agenda; green issues, blank tape levies and free museum entry all being championed. Even the shadow Trade and Industry spokesman, Gordon Brown, issued a document, Music: Our Cultural Future representing “the first time a major political party in Britain had published a serious policy for the music industry”. The great Red Wedge experiment was vindicated. In fact, in the 1987 general election there had been a 7 per cent swing to Labour by 18-to-24-year-olds. With six million young people not registered to vote – a statistic still compatible with 2016 – Red Wedge’s campaign “Don’t Get Mad. Get Organised” gave sobering credence to the alliance between pop and mainstream politics.

My Walls Come Tumbling Down book charts this explosive era of political and cultural activism through the voices of over 100 contributors including Kinnock, Tom Watson, Angela Eagle and Peter Hain. The narrative’s starting point is the infamous outburst by a drunk Eric Clapton, at the Birmingham Odeon in 1976, when he praised Enoch Powell.

In response, counter-cultural grassroots activism calling “for a rank and file movement against the racist poison in rock music” built under the banner Rock Against Racism and with the mechanical support of the newly formed Anti-Nazi League soon became a national, and later international, cultural phenomenon. Radicalised punk rockers and first generation black reggae artists united on stages, at carnivals – 50,000 in Manchester, 80,000 in Victoria Park, Hackney, 150,000 in Brockwell Park, Brixton – and on the streets to confront the emergent fascist organisation, the National Front. There were street confrontations in many cities across the UK but more often it was the power of music galvanising and bringing people together under a common cause for good. By 1979, as an electoral force, the National Front was crushed. And yet, a new right wing rhetoric emerged – “we are in danger of being swamped by an alien culture” – and a Thatcher government bent on class war and the annihilation of socialism.

This extraordinary and pivotal period of British social history, in which the roots of New Labour are clearly visible and, with startling prescience, mirrors the state and demands of the current political landscape, will be discussed at the party conference. It promises to be an incredible and critical debate around racism, gender inequality and social and class divisions.

Walls Come Tumbling Down: the music and politics of Rock Against Racism, 2 Tone and Red Wedge is published by Picador.

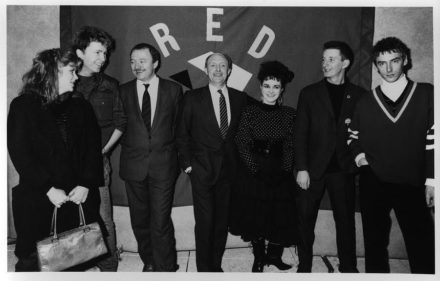

Daniel Rachel, Tom Watson, Labour deputy leader, Annajoy David, co-founder and political co-ordinator of Red Wedge and Peter Jenner, music industry manager and record label owner will appear at Walls Come Tumbling Down: A politics and music fringe event covering Labour, Red Wedge and the need for a new cultural alliance at Room 11A, ACC Liverpool on Tuesday 27 September at 7pm.

Picture: Steve Rapport.

More from LabourList

‘Is there an ancient right to jury trial?’

‘To tackle the housing crisis, the Treasury must rethink how it values social housing investment’

‘Labour action on extreme poverty can stop voters going Green’