In 1998, as a new minister, I took on responsibility for the New Deal for disabled people. We knew that the great majority of people out of work on health grounds would like to have a job. For the first time, government committed seriously to new ideas to help. Many were experimental. But, as the New Deal developed, there was steady progress in reducing the disability employment gap – that is, the difference between the employment rates of disabled and non-disabled people.

In 2011, the coalition scrapped the New Deal and introduced its work programme. The coalition’s programme dealt with all jobseekers, whether available for work and claiming jobseekers allowance (JSA) or out of work on health grounds and claiming employment and support allowance (ESA). Progress in reducing the disability employment gap came to a halt.

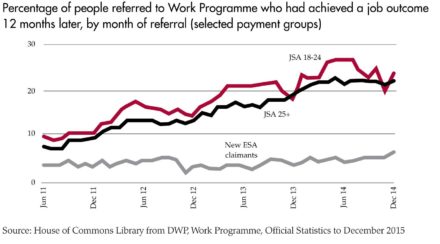

House of Commons library analysis shows how badly ESA claimants fared:

The government’s invitation to tender for the work programme said in 2010 that, if there was no programme at all, 5 per cent of new ESA claimants would find a job within twelve months. For most of its life – as the graph shows – the work programme was worse than doing nothing.

The National Council of Voluntary Organisations commented in July that the work programme: “has largely failed those with more complex needs or barriers to employment. For many charities, it has provided an abject lesson in how not to outsource public services, particularly for vulnerable people.”

The Conservatives’ 2015 election manifesto adopted the target – proposed by Scope in 2014 – of halving the disability employment gap. There is, however, no sign of measures to deliver so ambitious an aim. Further proposals are expected before the end of 2016. They will be keenly scrutinised to see if they can meet the challenge.

I believe four steps are needed:

Firstly, dedicated employment support for people claiming employment and support allowance (ESA) should be introduced. Labour’s 2015 election manifesto proposed “specialist support … to ensure that disabled people who can work get more tailored help.” Supporting JSA and ESA claimants in the same programme has failed.

Evidence from Australia suggests that programmes which focus purely on disabled people do better for disabled people than those which try and support everyone. The access to work scheme funds workplace adaptations for disabled people, and has been run down since 2010. It should be expanded.

Secondly, commissioning should be localised, bringing together Jobcentre Plus, councils and the NHS. Huge regional work programme contracts have squeezed out good, local organisations with specialist expertise. Contracting and, progressively, commissioning should instead be carried out locally. Local authorities, colleges, local employers and the NHS – the only provider of integrated placement and support services which have proved very effective in supporting people with mental health problems back in to employment – should be round the table. That kind of integration is feasible in a city region. It isn’t feasible in Whitehall.

Thirdly, in two years’ time, we will have had ten years’ experience of employment and support allowance. It will be time for a thorough review of the benefit, and in particular to consider whether major changes should be made to the work capability assessment.

Contributory ESA is paid – irrespective of other household income – to claimants who have been in recent paid work. The coalition introduced a twelve month time limit. Beyond that, ESA is now reduced pound-for-pound for other income. After a lifetime of work, someone out of work on health grounds who has a spouse with a very modest income is now entitled to no benefit support at all after twelve months.

This is unfair, and penalises work. Contributory ESA should be payable for at least two years.

Fourthly, direct support should be given to employers of people with health impairments, including consideration of new subsidies. Labour’s 2015 election manifesto proposed that for JSA claimants there should be “a guaranteed, paid job for all young people who have been out of work for one year, and for all those over 25 years old and out of work for two years”. The proposal was inspired by the success of the job guarantee offered to young people in Labour’s future jobs fund in 2009-10. A six months wage subsidy ensured sufficient jobs were available for the target group.

A similar initiative could increase the jobs available to ESA claimants. An incoming government should pilot a variety of approaches. It may well be most effective to subsidise employer support, rather than wages

Stephen Timms is the Labour MP for East Ham and was shadow minister for employment 2010-2015.

More from LabourList

EXCLUSIVE: Usdaw General Secretary writes to PM ‘frustrated’ regarding changes to Employment Rights Act

Think tanks and MPs call for targeted response as Iran war impacts cost of living

‘This Labour Government needs to fix the Tory student loan fiasco’