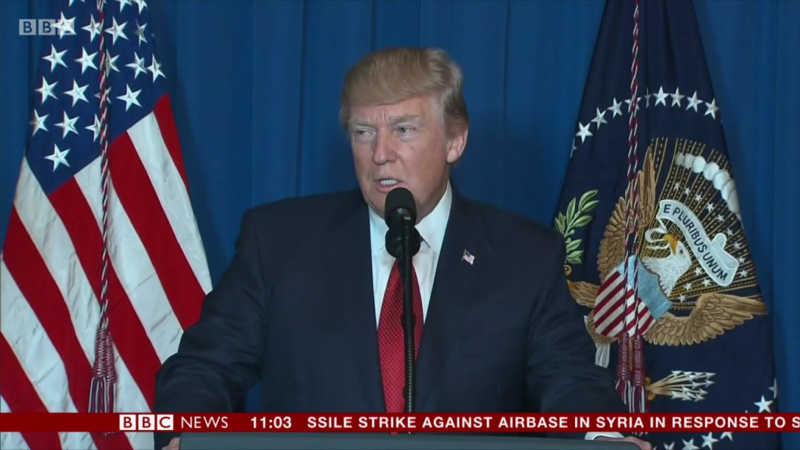

In the wake of last week’s US intervention in Syria the European left needs to decide how to respond to president Trump and the erratic, nationalist foreign policy he has brought to the White House.

The answer cannot be to disengage. The US is our most important and powerful partner: we share values, we trade together, we love each other’s cultures, and our security interests are intertwined. These deep transatlantic bonds will outlive the term of office of a single man.

But the answer cannot be business as usual either. The question is not only how close does Trump want to be to us, but “how close do we want to be to him?”, as Labour’s shadow foreign secretary, Emily Thornberry, writes in a new Fabian Society pamphlet published today.

In the democracies of Europe, mainstream political parties, governments and the EU institutions all have a fundamental commitment to human rights and international law. President Trump does not, whatever the motivations that lay behind his action in Syria.

He is the first American president to explicitly renounce past-1945 provisions such as the prohibition on torture or the pillage of conquered nations. His predecessors may have breached rules covertly or sought to blur their boundaries, but Trump’s open rejection of global standards is different. It must be publicly contested, no matter how awkward or inconvenient that may be.

But this is not the only way in which relations with the US will need to change. The US may use its military muscle when it chooses, but under Trump it will engage and lead less often, for “America First” implies a new isolationism alongside a new nationalism.

Where the US refuses to tread, Europe will need to step up, not to compete with American but to fill the vacuum. Once this might have been impossible, but the world is now multi-polar and Europeans can work with other powers while the US stands by, on issues such as trade, international development and climate change.

The values and leadership of the European left will be essential. The aim must be to prove that multilateral institutions and high global standards can be to everyone’s advantage, working with strong democracies in every region of the world. We can also forge partnerships with progressive forces within the US who share our goals: responsible businesses, charitable foundations, cities and states. And where our interests align, European democracies must have the confidence to work positively with China, even if US-China relationships turn sour.

On security, relations between the US and Europe must remain strong of necessity. European nations must raise their game and prove their commitment to their region’s defence. But they must also insist on America’s commitment to the principle of mutual security as well as the reality that this can only be achieved through international law and a strident challenge to those who breach it, including Russia. This is a lesson that the leadership of the Labour party may be in danger of forgetting.

By championing the rules-based, multilateral liberal order, rich democracies beyond the US can earn renewed global respect and build soft power. This will matter if the US refuses to take steps to prevent and tackle tensions and conflicts. For example, while the US may be robust in using military force against Isis or Assad, it is likely to do far less now to address the causes of terrorism and civil war. Europe must build the trust it will need to lead in this domain.

Europe also needs to decide how to respond to the wild unpredictability of the Trump administration, which seems to be half-temperament, half-tactic. The new president may believe uncertainty brings strategic advantage but, really, erratic brinkmanship only heightens international tensions.

In response, Europe should explicitly set out to de-risk global relationships, by creating room for dialogue and co-operation even where the US has chosen a different path. This approach is particularly important with respect to nuclear weapons, where president Trump seems unaware of the dangers that his overturning of US policy and doctrine could bring.

In all of this, we write as if the nations of Europe share a common view and policy. But, of course, Donald Trump’s term of office will coincide with the UK’s departure from the EU. There is a grave risk that, in dealing with Trump, the government will choose to stand apart from its European allies, even though our interests are aligned.

It would be a huge mistake for the UK to deepen its foreign policy ties with the US under Trump, just because it has chosen to weaken its European partnerships. We have already seen the danger, when Theresa May initially refused to condemn President Trump’s “Muslim ban”, for fear of derailing future talks on trade.

Populists and neo-conservatives will try to use Trump’s presidency to wedge apart UK and EU diplomacy. Progressives in the UK and the rest of Europe must not let that happen. We must undermine Europe’s homegrown nationalists and protectionists, by tainting them by association with the Trump regime. And we must make the case for intensive joint action by the UK and EU that strengthens multilateralism and the application of our shared values.

The way that the UK and the EU work together to respond to Trump can set the tone for a foreign policy partnership between Britain and the European Union for decades to come.

Andrew Harrop is general secretary of the Fabian Society and Ersnt Stetter is secretary the Foundation for European Progressive Studies. Together they have written a contribution for the Fabian Society pamphlet, The Age of Trump: Foreign policy challenges for the left, published today.

Want to support LabourList’s dedicated coverage of the party? Click here.

More from LabourList

‘Labour’s problem isn’t the Green Party – it’s complacency’

‘Ministers have vowed to protect women, but aid cuts will abandon them’

‘Farage lost and blamed Muslims. The data doesn’t support his suspicion’