The many ways of Essex

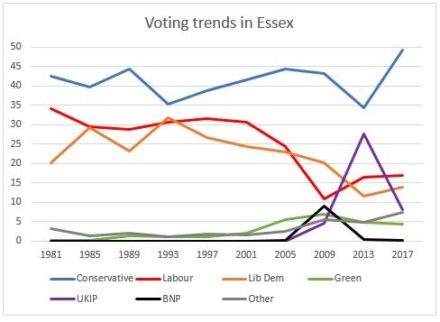

It’s simplistic to say the Tories scored a victory by winning back some of the UKIP vote this year. Not in Essex where the disenchantment with Labour among its traditional supporters began between 2001 and 2005 in Blair’s second term. It’s really a story of Labour’s gradual failure over 15 years. On the upside, it seems to have passed the worst point seen in 2009. However, there is no sign of an imminent return to a 1990s levels of support.

The Conservatives have been consolidating their position in Essex for over 20 years, partly due to gentrification and an ageing population. The Liberal Democrat vote started falling in the mid-1990s, largely to the benefit of the Tories.

The Labour vote started falling after 2001, particularly after the Iraq War which completely gutted some CLPs of membership as activists quit in anger.

In 2009, a tiny proportion of Labour’s traditional voters issued a cry for help by making protest votes for the neo-Nazi BNP – not due to racism, but a deep sense of despair. In 2013, some of those votes went to UKIP, which also ate significantly into the Tory vote. But, with the Tories faring worse from the UKIP challenge, by 2013 Labour was able to regain most of its 2009 losses. The Tories only turned the tide this year due to Brexit, which was supported by around 60 per cent of Essex voters.

The case of Harlow

In 2017, the only change for Labour has been the impact of the UKIP vote going to the Tories in Harlow. But Harlow flips between Labour and Tory all the time. It’s not simply a case of UKIP as a “gateway” to the right for traditional Labour supporters, although the Tory vote is higher than it has ever been in Harlow and Brexit made some difference to its gains – 68 per cent of Harlow voted to leave, which equates to the Conservative and UKIP vote combined.

Harlow is a bellwether for the country as a whole – because it tends to vote for a party that wins the general election – and the Tory vote there was around 50 per cent. With UKIP not standing candidates (due to a clerical error), Greens sitting it out (amid suggestions they were encouraging tactical voting for their 2 per cent) and the Lib Dem campaign non-existent, the Labour vote also increased. In Harlow North, the Tories regained the seat with 50 per cent (up 22 per cent and taking the bulk of UKIP’s 26 per cent of the vote in 2013) while Labour won 41 per cent of the vote (up four per cent). A Labour majority of 9 per cent was turned into a Tory majority of 9 per cent on a higher turnout.

Harlow is likely to remain Tory next month by taking around four in five UKIP votes. However, the constituency didn’t see a collapse of the Labour vote, but a slight increase due to a lack of competition. But Labour has not been wiped out in Essex and is doing a lot better than when Gordon Brown was prime minister. Yet, this isn’t the basis to win a general election. There has to be something new – a New Labour party isn’t what Essex would vote for even if it isn’t convinced by Corbyn.

Rebuilding and recharging

Corbyn’s election has not been a disaster for Labour, but put it on the path to rebuilding. CLPs in Essex are now as big as they were ahead of the 1997 victory, largely due to the enthusiasm for a genuinely alternative agenda and a cleaner politics. A return to the New Labour era would be a disaster, both in snuffing out the enthusiasm for change among the new influx, and among the electorate as a whole, some of whom found Blairism disingenuous.

The rebuilding of CLPs has ensured the Labour vote did not collapse in the local elections. It remains to be seen what will happen in June, but if the pattern of voting is repeated there will not be a collapse – and nor will there be electoral gains.

If Labour is defeated in June and if Corbyn then does the right thing in resigning, the Labour party elite should think long and hard about whether aping the Tories with a neo-liberal austerity agenda would achieve anything. Certainly, campaigning to remain in the EU or holding another referendum would send Labour plummeting. In areas like Essex, there is a groundswell of disillusionment with the status quo that was expressed in the referendum and that has to be acknowledge and respected.

While Corbyn as a leader provokes some doubts, his agenda resonates with many Essex men and women. What does this mean in policy terms? The answers will vary from constituency to constituency, but housing, health and education are significant areas of anxiety.

The self-employed “white van man” and minicab driver will often unwittingly reel out political demands that are indistinct from the Corbyn social agenda, yet will be reluctant to vote Labour because of a leader who cannot command a party in parliament.

In short, Corbyn’s social and economic policy platform and its broad thrust is right for Essex, it is not a turn-off. It just needs a convincing salesman with an Essex accent.

More from LabourList

‘What Batley and Spen taught me about standing up to divisive politics’

‘Security in the 21st century means more than just defence’

‘Better the devil you know’: what Gorton and Denton voters say about by-election