On June 24 last year, the day after the EU referendum, I suddenly found myself, along with many others, living in what felt like a different country. I voted remain but, if you did not, then hear me out.

The Belarusian writer Svetlana Alexievich said in a recent interview in the Financial Times, “To be in conflict with the authorities is one thing … but to be in conflict with your own people – that is truly terrible.”

Disagreeing with politicians is perfectly ordinary, if not a democratic duty. But being at odds with the majority – albeit a slight one – of your fellow voters challenges your very sense of self. A year on from the referendum, I am as resolute in my vote as I am sure that many leave voters are. However, I am increasingly convinced that the answer we got had little relation to the question we were asked. Leaving the EU will do little to address the fundamental issue at heart of the result: power, or a lack of it.

I grew up in the post-Thatcher 1990s on small housing estates in villages in north Nottinghamshire and south Yorkshire, areas hollowed of their former industrial economic power. The distribution of defunct coal mines in England is testament to the historical importance of industry to the midlands, Yorkshire, the north west and the north east. In the two decades from 1957, when employment in the coal industry reached a modern peak of 710,000, almost half a million jobs disappeared, disproportionately affecting these areas. This is not to mention the decline of manufacturing and of many other heavy industries.

I am not calling for a return of the coal industry—we should do more to invest the high-tech renewables sector to provide well-paid jobs in industry now—but I believe that both sides of the referendum campaign missed the real cry of the electorate. It was one that had been suppressed for more than three decades.

After the massive spike in unemployment in the early 1980s, the attitude of many people in deindustrialising areas became engrained: take any job, anywhere and be grateful. The scars of mass unemployment run deep and wide, just like the pits themselves. This period had a profound impact on how people calibrated their expectations. No matter the insecurity, inadequate pay, indignity or poor conditions, any job was what mattered. Power, especially economic power—of which these communities had been denuded—came from work, any kind. Although not worthless, people certainly became worth less. The real effect of deindustrialisation was to produce a generation of people suddenly disempowered. Their futures had been decided for them, and it was nothing if not uncertain. But live with insecurity long enough and you no longer feel fearful, but emboldened. The grief of loss hardens into righteous anger.

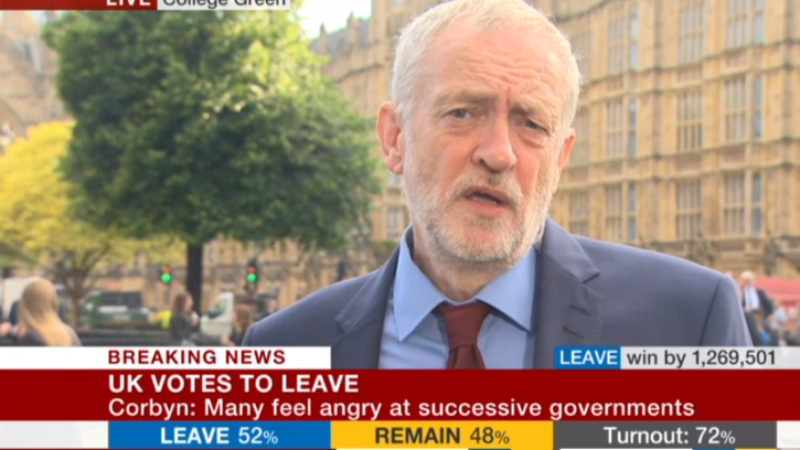

Which brings me back to June 24 2016. It may have seemed on that day that I was in conflict with my people, as Alexievich described, but I was not. Nottinghamshire and South Yorkshire voted predominantly to leave the EU, with Mansfield, Doncaster and Barnsley having some of the strongest leave majorities in the country.

But at core I suspect this was not even mainly about the EU. Most people pay little attention to it, as they do to Westminster, and have little familiarity with it, as they do with Westminster. People saw that their communities were changing fundamentally—mainly because of generational economic changes—or not developing enough, and that once again, as a generation before, they had little say in the matter.

Because every vote mattered, the referendum gave them each a meaningful voice, and they made it heard. I understand why. It was not to do with racism or ignorance, as some have insultingly suggested; it was about having been disempowered again and again, and admirably standing against it. On this point, I am with them wholeheartedly.

The shame is that the vote will do little to empower these communities. Moving legislative authority from Brussels to Westminster brings it hardly any closer to communities in the UK, just from one distant bureaucracy to another. The Leave campaign did not advocate for radical decentralisation that would meaningfully shift the balance of power in favour of marginalised communities, but then again nor did the Remain camp. Both misunderstood, perhaps because both were mainly run by people — the Eton alumni — with no understanding what it is to be disempowered.

It is not about voluntarily sharing power with your allies, with the ability to withdraw at any time. It is about being impotent, involuntarily passive and vulnerable as changes are enacted upon you, just as they were enacted on people in the UK’s former industrial centres. The UK was none of these, but the message certainly resonated because it was so familiar.

Labour must hear the real cry of the referendum vote. It must promote an agenda of radical decentralisation, empowering people as Labour at its best has always done. Labour did better than expected in the 2017 general election, but it did not win back the working-class vote in anywhere near the numbers necessary to win power. In order to do that, it must focus on winning power in order to redistribute it.

More from LabourList

‘A third way approach is needed to protect children online’

‘Lammy’s jury trial cuts risk worsening racial bias in justice system’

‘Is there an ancient right to jury trial?’