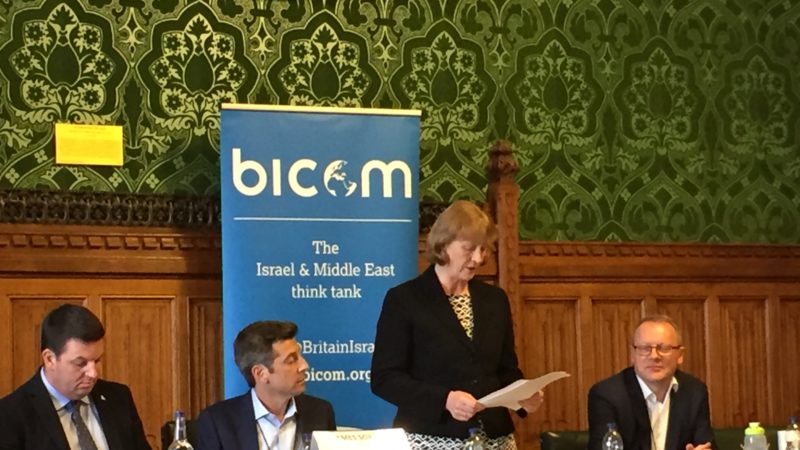

I introduced a cross-party bill in support of the International Fund for Israeli-Palestinian Peace in January and I have also spent time in Washington working with The Alliance for Middle East Peace (ALLMEP) to help garner support for the Fund on Capitol Hill. The great value of a new report published by BICOM and written by Ned Lazarus, ‘A future for Israeli-Palestinian peacebuilding’ is that it addresses three of the main objections privately presented by DfiD to funding people-to-people work.

1) That Palestinians do not want to take part as they see such projects as entrenching the status quo;

2) That it’s hard to reach the communities who are most likely to reject peace through these projects;

3) That it is hard to demonstrate a macro-level impact on policy or development objectives even where projects do alter individual perspectives.

That’s why I have put down a written question to the Secretary of State for International Development asking her department to urgently assess the findings of the report, which I believe has three great strengths.

First, the report shows that people-to-people work is not a fluffy afterthought when it comes to moving the peace process forward. The reports assessment of peacebuilding is hard-headed. It tells us that the civil society dimension of peacebuilding is about very practical politics. It’s about how to garner the necessary public support for any future agreement and how to ensure that that agreement can weather the challenges it will inevitably face in the medium to long-term. Peacebuilding works: it creates constituencies for peace, changes attitudes, humanises the other, builds trust and empathy, improves quality of life on the ground and, as Lazarus shows, can even change government policy.

Peacebuilding is essential for peacemaking. Lazarus notes the large majorities which backed the Good Friday Agreement in the referendum, and points out that these were in part the result of the groundwork laid by the International Fund for Ireland. We need to remember, too, that support for that agreement was sustained through some attempts to destroy it, most notably at Omagh.

The second strength of the report is its demonstration that those working in this field are creatively rethinking how to build broad and enduring constituencies for peace.

Within Israel, the effort to build constituencies for peace beyond the secular, urban and educated groups that have long been the mainstays of the “peace camp” shows a new realism about the need to increase legitimacy for peacebuilding. We see that in both the recognition of the need to understand Israel’s legitimate security concerns and the attempt to reach out to politically and religiously conservative communities. Indeed, I know that the British Embassy in Tel Aviv has been part of this effort in terms of some of the work it has been supporting with Haredi women.

The “anti-normalisation” rhetoric of the BDS movement provides an enormous challenge to peacebuilding work in Palestine. However, the Women Wage Peace marches – bringing together Palestinian women and women from religious and Arab communities in Israel – showed what can be done. I know from my discussions with ALLMEP that when programmes offer real wins for the community, do intra-group work, and integrate alumni into the core of their programme, they meet with success.

The Olive Oil Without Borders program in Nablus is a great example, with thousands of farmers wanting to participate. Indeed, the biggest problem many groups have found is that demand has outstripped supply. Kids4Peace have five (mainly Arab) families for each spot they offer.

The third great value of this report is that it provides us with a much-needed evidence base, built upon robust evaluations, which should give us the confidence to challenge policymakers who dismiss the idea that people-to-people projects actually produce results.

Ned Lazarus’s own activism at the Seeds of Peace project not only provides us with the crucial statistics, but also some truly inspiring stories about the paths its alumni have taken later in life.

We now have important evidence about what works, in particular the need for coexistence work to offer sustained engagement, bringing people back together at different stages of their lives.

Examining both cross-border and shared society peacebuilding initiatives, the report shows examples of real change on the ground: the growth of integrated bilingual schools within Israel and the placing of hundreds of Arab teachers in Jewish schools; the Israeli government’s decision to equalise resource allocation in terms of Arab Israelis; and the breakthroughs engineered by EcoPeace to ensure Palestine and Jordan receive the water resources they need.

The report makes a plea for more funding for peacemaking from the International community and the UK government. These are not party political points: Conservative Friends of Israel has worked closely with Labour Friends of Israel on the need for greater coexistence funding and I was pleased to have the support of a number of its parliamentarians for my 10 minute rule bill.

The government has admitted that its already pitiful support for coexistence work – 150,000 in 2015/16 – was eliminated altogether in 2016/17. The report refers to the claim that the Government spends £400,000 on coexistence work. However, the government not only refuses to provide further details of what this sum is being spent on (beyond vague references to building constituencies for peace within Israel), it does not itself class the sum as coexistence spending.

We have been told repeatedly that DfiD is planning a new package of support for coexistence work and that this would be up and running for the new financial year, but we are now one-third of the way through that year. Insecure funding is particularly harmful for work which requires sustained, long-term support.

In conclusion, I have a simple question for those in DfiD and the FCO who are resisting both increasing coexistence funding and providing any form of support – even rhetorical – to the International Fund: can you point to anything in your current funding that has moved the conflict closer to resolution? Because I believe, and this report demonstrates, that people-to-people work, supported over the long-term and operating at scale, can help to do so.

BICOM’s study “A future for Israeli-Palestinian peacebuilding” is the most comprehensive review of peacebuilding programmes ever conducted. It is based on 20 years of evaluation data and extensive field work, and proves that peacebuilding programmes work. It can be read in full here.

More from LabourList

‘A third way approach is needed to protect children online’

‘Lammy’s jury trial cuts risk worsening racial bias in justice system’

‘Is there an ancient right to jury trial?’