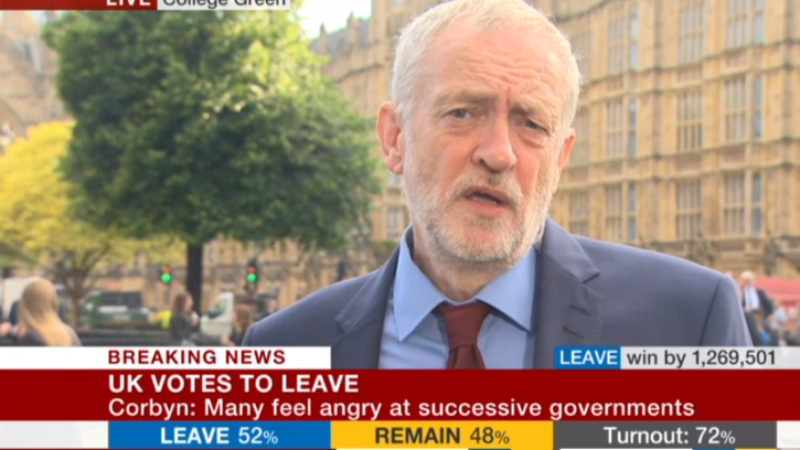

After two years of criticising Jeremy Corbyn and one spent trying to depose him, Labour MPs witnessed a massive increase in the Labour vote this June, with the party winning seats against all expectations.

Many on the left and those in Momentum see this as the perfect opportunity to bring in new party legislation to make it considerably easier to deselect rebellious Labour MPs. Chris Williamson, a key Corbyn ally and a supporter of introducing mandatory re-selection, said, “No MP should be guaranteed a job for life and it’s crucial that we all get with the times… Yes Labour is a big church, but we currently have a large bulk of MPs who represent one relatively small tendency in the congregation. To keep Labour fresh and updated we need MPs who can win the support of the mass membership.”

This development is hardly surprising considering the methods used by many Labour MPs in the aftermath of the EU referendum and the antipathy shown towards a leader elected by a huge margin the previous year. Those on the right of the party are emphatically opposed to mandatory re-selection, but why shouldn’t the majority in local party constituencies be able to deselect MPs who acted completely in opposition to their wishes, especially if there is little prospect of Labour electoral defeat?

Despite this legitimate anger, introducing mandatory reselection would be bad not only for the Labour Party, but the country too. For evidence of the unintended consequences of mandatory reselection, we should look to the US. Just like in Britain, US elections operate on a first-past-the-post system that means that many members of congress are extremely safe in their positions. Gerrymandering, restrictive voter ID laws and limited voting access have further exacerbated this.

Furthermore, there are occasionally challenges to the incumbent politician, with an election to decide who the party candidate will be in a forthcoming national election. The consequence of this is that members of congress in safe seats have become more accountable to their local parties than to the people who elected them. They become beholden to specific interest groups who do not represent a majority within the constituency, or maybe even in their own local party, but do represent a majority of the few who bother to vote in re-selection elections.

Arguably the most notable of these groups is the gun lobby, who consistently manage to successfully lobby against gun control, even though the majority of the population are in favour of greater restrictions.

Do we really want politicians who represent Labour to be captured by a pressure group in this manner and be tempted to put their interests ahead of those of the party or country? Furthermore, those backed and elected by special interest groups tend to be chosen for their dogma on specific issues, rather than their political abilities.

Existing politicians may be reluctant to take actions for fear of facing local challenges, even if such actions are either necessary or good. The Republican politicians chosen by this system are unable to enact new policies, despite having control of both the house and the senate, as they cannot agree the compromises often essential to enacting policies in as large and diverse country as the US.

Whilst I would not expect Labour to operate in as dysfunctional a manner as the Republicans, we should question whether introducing a party process which encourages ineffectiveness and dogmatism would be conducive in building a Labour Party which can achieve its goals.

Labour is – by electoral necessity – a broad church, where different sides of the party need to work together. Nothing epitomises this better than the recent general election, as members from the hard-left to the centre have campaigned tirelessly to get Labour MPs elected, even if that MP did not share many of their political views.

If we introduce policies that undermine and divide our broad church, then we not only diminish our ability to work together to change this country for the better, but also threaten our chances of winning elections by electing politicians overtly concerned with relatively minor issues, rather than the policy proposals that the public are most concerned with.

Labour did much better than expected in the general election because Corbyn put to one side the policies which had divided the party, such as Trident renewal, and concentrated on the common ground that all ends of our party agree on – properly funded public services, affordable housing and greater investment in our economy. The point of the Labour Party is to govern; if we create an internal party system which makes that less likely then clearly the party system is inappropriate.

Despite rejecting mandatory re-selection, things must not continue in the manner of the last two years. It is time for Labour MPs to start acting and speaking responsibly. They must acknowledge and respect the broad church nature of the party, the necessity of taking actions which maintain it and the compromises that many on the left made under the Blair leadership.

It is unacceptable for MPs to orchestrate staggered resignations in an attempt to get rid of a democratically elected leader, just as it is unacceptable for the shadow chancellor to call those said MPs “useless” (I have missed out a few words). Only with a united, responsible party will we achieve the Labour government that we so passionately desire.

James Greenwood is a Labour activist in East Ham in London.

More from LabourList

‘A third way approach is needed to protect children online’

‘Lammy’s jury trial cuts risk worsening racial bias in justice system’

‘Is there an ancient right to jury trial?’