The leadership of the German SPD can breathe easy again: in the end, they won a two-thirds majority in the membership ballot on entering a third grand coalition as the junior partner to Angela Merkel’s CDU.

For many, this result means one thing above all – ‘stability’. Germany will continue with the same government and the same raft of policies — including no new taxes for the rich and no new net public debt — despite combined losses of 13.7 per cent for the CDU & SPD in the last election.

But at what price comes this ‘stability’? Time and again, centrist governments unwilling to tackle inequality have driven the growth of the far right and weakened the left. So it was with the two previous Merkel-led grand coalitions. This time, though, it’s worse – the far-right, openly racistAlternative für Deutschland (AfD) will now lead the opposition.

Already, the AfD’s toxic agenda is infecting public discourse, with the poorest Germans currently being encouraged to blame refugees for using ‘their’ food banks. The 45 richest Germans now own as much as the bottom 50 per cent. In Europe’s richest country, 1.5 million people – including over 300,000 children – regularly rely on handouts of food that has passed its sell-by date. Rather than scandalise the failure to make Germany’s top 0.1 per cent to pay their fair share, the weakest in society are being grotesquely played off against each other.

For so many lower-paid Germans, the SPD is the party of pushovers who’ve betrayed their interests. The last grand coalition at least introduced a minimum wage – but that still wasn’t enough to stop the SPD crashing to its worst-ever post-war result. This time around, the coalition agreement foresees no such stand-out left-wing project. What can the SPD offer voters at the next federal elections in 2021?

And why on earth did SPD members vote for another grand coalition at all?

There are two obvious answers:

Firstly, the lack of a level playing field. Having promised a “particularly fair” debate, the SPD leadership delivered exactly the opposite. On social media, the NoGroKo campaign won by a country mile – but half of SPD’s 460,000-strong membership is over 63, and the majority of these members cannot be reached by Facebook and Twitter. Opponents of the grand coalition, or GroKo, were prohibited from making their arguments in party publications, whether in print or online.

‘Dialogue Events’ were held in which opponents were not allowed to address the hall. Members were bombarded with pro-GroKo mails from party headquarters while opponents were given no access to the membership database. And in a move that gave succour to ballot-rigging autocrats the world over, the 463,000 postal ballots were accompanied by a 3-page letter from the leadership telling members to vote yes. Counter-arguments were not included.

Secondly, fear. The latest polls put the SPD as low as 15.5 per cent. With the party leadership insisting that voting down the GroKo would inevitably force new elections (which wasn’t true – minority government was also a possibility), many members understandably took fright.

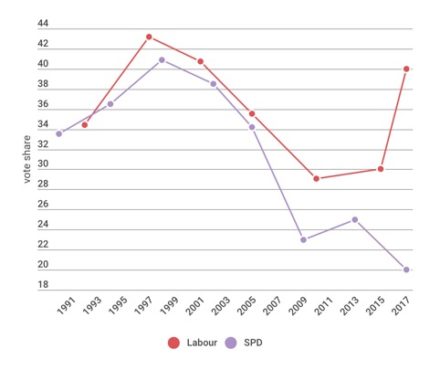

But the news isn’t all negative. Younger members were overwhelmingly against the GroKo. Given the party’s top-heavy age structure, demographic change is coming to the SPD sooner or later, whether it likes or not. These younger members are looking more and more to Labour under Jeremy Corbyn, and specifically to Momentum, as a model for genuine and credible political renewal. It’s not hard to see why: Labour’s electoral fortunes can be mapped almost exactly onto the SPD’s since the ’90s – until the 2017 election, when Labour shot up to 40 per cent and the SPD crashed to its lowest-ever post-war result. (The comparison raises serious questions as to how Labour would have done if Corbyn had not made it onto the 2015 ballot.)

And in spite of the result, a seismic shift has already taken place within the SPD. Traditionally, SPD leaders have been picked in back-room deals, then elected unopposed at conference. Two weeks ago, the attempt to pre-emptively install Andrea Nahles as the successor to the hapless Martin Schulz led to a grassroots outcry and a humiliating climb-down within 24 hours.

As leader of the parliamentary group, responsible for pushing through GroKo policy, and a former labour minister who pushed through a raft of exceptions to the minimum wage, Nahles is powerful. But she is widely disliked and seen as particularly unsuitable to lead the SPD through any kind of renewal.

Having been given a taste of member-led democracy in the coalition vote, a petition has been started asking for the whole party to be given a vote on the leadership, rather than just conference delegates. With mainstream social democratic parties crashing to oblivion all around Europe, Labour’s member-led democracy is the only viable model out there for genuine renewal.

Steve Hudson is a Momentum activist and a member of Labour and the SPD.

More from LabourList

‘Help shape the next stage of Labour’s national renewal through the 2026 NPF consultation’

‘AI regulation is key to Labour’s climate credibility’

Ben Cooper column: ‘Labour needs to rediscover its own authentic populism’