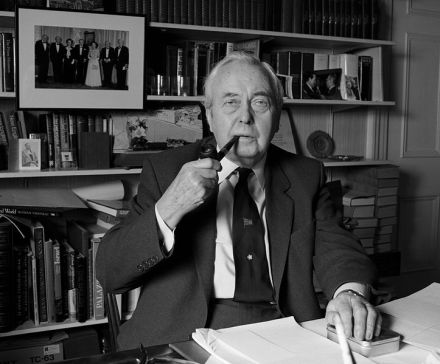

Harold Wilson is Labour’s most successful leader. This has long since been forgotten, but the House of Lords put him back in the spotlight on March 6th when two politicians who served under him, Bernard Donoughue and Giles Radice, gave lectures remembering him as Prime Minister.

Lord Donoughue drew on inside knowledge – he was one of Wilson’s ‘kitchen cabinet’ after the first 1974 election and set up the Number 10 policy unit. Although the term ‘soft left’ had not yet been coined, Donoughue sees Wilson in that tradition. This partly explains why the Blairites – deliberately – and the Corbynites – accidentally – have forgotten Wilson.

The basis of Wilson’s claim to success is his achievement in winning four of the five elections he fought. As Donoughue notes, this is unprecedented. Attlee won one and a half: 1945, followed by the narrow victory of 1950, when the writing was on the wall. Blair won two and a half: the landslide of 1997 repeated in 2001, followed by the narrow victory of 2005, when the writing was on the wall. Labour has not won an election since.

What did Wilson have going for him and what lessons can he teach us today? Donoughue touches on his being adored by Labour voters and “hated by the Daily Mail, itself a proof of his great qualities”. The route to being hated by the venemous Mail was his skill in leading the Labour Party, divided as always between the hard left and the hard right, though Wilson himself was fond of quoting the maxim “if you cannot ride three horses at the same time, you should not be in the circus”. (The Independent Labour Party always said this was invented by their 1930s leader Jimmy Maxton.)

The divisions were not yet toxic. Wilson came from the soft left, which Donoughue defines as “the familiar left-wing Tribunite ladder” up which Wilson climbed. But under Wilson, the left-right split did not become critical, though the social democratic right that was to later form the Social Democrat Party in the 1980s was already visible.

For Donoughue, Wilson’s “most valuable leadership quality was in understanding that the Labour movement has always contained a coalition of two distinct traditions”. He defines these as the liberal progressive intellectual elite on the one hand, and “the rank and file Blue Labour, including trade unions… concerned with the problems facing ordinary working people in everyday life” on the other. It is a simple sketch that needs more work, but Donoughue is right to see that bridging divides in the party was Wilson’s critical task. The peer’s comment that “neither side should… dominate and neglect the other, this time the Blue Labour core, with dire results in the referendum” makes sense.

The New Labour attitude to working people was toxic, but it would be sensible to note that Wilson’s attitude to what became the hard left was dismissive. Wilson had no time for Tony Benn, who like Wilson and Callaghan has largely vanished from public gaze. But that is partly due to New Labour, and Donoughue is right to suggest that the priority of Wilson as “improving the daily lives of working people from whatever class” seemed to New Labour utterly irrelevant, and this was the root of the rise of UKIP. Working people had been rejected by New Labour and the referendum of 2016 was payback time, largely in the old mining areas Thatcher once decimated.

Wilson healed the Labour split of 1972 over Europe with a referendum that he used in 1975 to unite rather than divide. The first referendum was a massive success, achieving a two-thirds majority against leaving the EU after the Tories had taken the UK into the European Community in 1972. It was the behaviour of the Blair-Cameron elite, dangerously out of touch with small town Britain, which allowed that consensus to be broken. And the first EU referendum has been forgotten: there cannot be another second EU referendum because the 2016 vote was the second.

Wilson alas no longer figures in a history written by the victors, namely the Blair New Labourites of the 1990s. However, as Donoughue says, their day is over, although they show no signs of understanding that the circus has moved on. They patronised the old Labour right wing, the unions and the anti-capitalist and pro-public service core of the party.

Donoughue argues that “it may be time to move Labour’s policies, as we did in the last election, towards the soft left”. This is the way to move, and in doing so it is vital to understand the legacy of Harold Wilson. We wait for Giles Radice to put his lecture into the public arena, but the recovery of Wilson’s remarkable career surely cannot be long delayed.

The full lecture can be found at Lord Speaker’s lectures: Harold Wilson: A Flawed Political Genius?

Trevor Fisher is a Labour member and a former member of the Labour Co-Ordinating Committee (LCC) executive, the Compass executive and the Rank and File Mobilising Committee (RFMC).

More from LabourList

Joani Reid resigns Labour Party whip after husband accused of spying

‘Labour won’t win back left defectors with squeeze messaging alone’

‘Help shape the next stage of Labour’s national renewal through the 2026 NPF consultation’