The Chancellor didn’t say a word about the rising level of homelessness in his budget delivered on Monday. I’m not just talking about the 169% increase of rough sleepers since 2010, visible on our streets across our towns and cities up and down the country, but of families living in temporary accommodation or people sofa surfing as they aren’t deemed a housing priority need. To this government’s shame, statutory homelessness has quadrupled to 18,000 a year over the period. This epitomises the neglect of too many of our citizens and reflects not just the Tory failure to ensure there are enough homes for us all, with social and affordable homes as part of that mix, but also of ill-conceived social security policies including their flagship programme, Universal Credit, which is contributing to this homelessness. One homeless shelter has said that the benefit reform is the reason a third of their residents are there.

Universal Credit may be based on principles that many supported at the start, including reducing child poverty and creating a simplified system, but concerns were raised very early on about its design failings. This was swiftly followed by cuts to UC in the infamous 2015 summer budget, which made it much less generous than legacy benefits. The Child Poverty Action Group and Institute of Fiscal Studies, amongst others, predicted that these social security cuts would increase child poverty to over a million by 2020, reversing all the gains that Labour had made.

Based on data of existing social security claimants, Policy in Practice analysed the number of people who will be affected by the UC roll-out and how much money they were set to lose. Before the budget, they estimated that approximately 3.2 million people would be worse off with UC roll-out, with disabled people and the self-employed losing out the most.

Policy in Practice redid their analysis based on the Chancellor’s announcement that UC would get £1bn for transitional protection over the next five years and an increase in work allowances of £1.7bn in 2023-24. They found that a significant number of claimants would still be worse off under UC: 2.8 million households by, on average, £58.75 a week or £3,055 a year. They also found that the increase in work allowances was particularly benefiting those who were already better off under UC.

Sick and disabled people who are in work are still worse off with UC, with the provisions made in the Autumn Budget having little to no impact in the majority of cases. These households (about 13% low income disabled households) will receive about £28 a week or £1,456 a year less, compared to legacy benefits. I cannot fathom the decision-making that concludes this is acceptable.

The second group that loses out are the self-employed. The transition to UC from legacy benefits was bad enough, but after the budget, self-employed people are set to lose £50.86 a week – the equivalent of £2,645 a year. The Minimum Income Floor, where the self-employed are assessed as working full-time at national minimum wage after 12 months, just doesn’t reflect the reality of these young businesses. These new entrepreneurs need to be encouraged to thrive, not penalised.

The analysis shows that these marginal changes to UC are not nearly enough given that since 2010, we’ve seen social security spending cut by nearly £40bn. As Labour pledged in last year’s manifesto, we need changes to economic policy to address the unfair tax burden and poverty pay. But we also need to radically transform our social security system. We cannot expect people who are living in such hardship and poverty to wait years for a Real Living Wage to kick in. And what about ill and disabled people who can’t work?

The Brexit deal we end up with is another factor. All the scenarios for the economy look pretty bleak, and it’s important we get a good deal. But whatever the outcome, those who have been suffering for years cannot be expected to wait possibly decades until the economy picks up before they are lifted out of poverty.

The 1942 Beveridge Report was the basis for a new welfare state set up after the Second World War, when the debt to GDP ratio was over 250% (it’s currently 90%). Under Beveridge, we established the NHS in 1948, expanded social security and our education system. It was heralded as a revolutionary system that would provide “income security” for citizens “as part of a comprehensive policy of social progress”.

Since then, society has changed. The pressures from globalisation, automation and an ageing society means that we need to develop a new, sustainable social security system that we can be proud of. Now is the time to draw up a new Beveridge report for the 21st century, defining a new social contract with the British people, addressing the poverty, inequalities and indignity that millions are enduring. Let’s bring hope to a new generation, as we did 76 years ago.

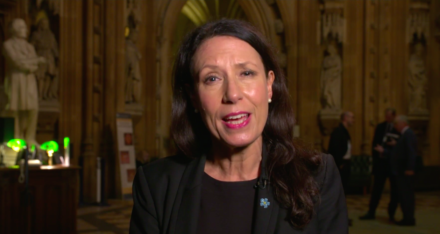

Debbie Abrahams is MP for Oldham East and Saddleworth.

More from LabourList

‘A third way approach is needed to protect children online’

‘Lammy’s jury trial cuts risk worsening racial bias in justice system’

‘Is there an ancient right to jury trial?’