There is an emerging view on the left that if Jeremy Corbyn is able to strike a Brexit deal with Theresa May, the national conversation will refocus on domestic concerns such as the NHS, child poverty, and the housing crisis. As the architect of Labour’s Brexit plan — it was picked up by the party from a 2017 paper called ‘the shared market‘ that I wrote with my colleagues at IPPR — it is worth setting out why that probably won’t be the case.

The shared market plan has three foundational assumptions. First, that a close result was a mandate to continue our economic partnership on a new political basis, with a compromise on freedom of movement that would preserve but modify it. Second, that 46 years of economic integration could not be unwound in the space of two years, even if that was thought to be desirable (it isn’t). And third, that ordinary people’s livelihoods and living standards should not be sacrificed to delusions of grandeur about the future or misty-eyed nostalgia for the past.

As a result, the ‘shared market’ approach focused on how the new relationship should be structured. First, we proposed a customs union where a set of safeguards would be negotiated to ensure that the UK was not unfairly exposed in trade negotiations, including consultative mechanisms and volume of trade thresholds. Second, we argued that rather than being permanently locked into the single market without a role in decision-making, the UK should be outside the single market but aligned to it. This would be dynamic, constantly updated to avoid a gap opening up as regulation advances. The UK would retain the sovereign right to diverge if there was future regulation that it found intolerable — with clear and proportionate consequences for preferential trade arrangements — thus addressing a key concern of Leave supporters while not attempting ‘have your cake and eat it’. Third, enforcement and adjudication would be carried out by a new UK supervision authority and UK Court of Justice, which would include representatives from both the UK and the EU.

The plan also proposes a compromise on free movement that would preserve but modify it, just as the EU has done with other third countries. This would involve better enforcement of existing rules and the adoption of the Swiss local-labour market preference system (agreed between the EU and Switzerland following a referendum in 2016). The latter means that in selected regions and sectors where there is high structural unemployment, residents are given priority in job applications over other EEA citizens. In the UK, this might mean that local residents would be given priority for manufacturing jobs in the North and Midlands where deindustrialisation in the 1980s and 1990s resulted in high structural unemployment to this day. The EU says this does not violate the principle of free movement.

Sounds like a deal that works for everyone? When the plan was first published, it was positively reported by the Remain-backing Financial Times as well as the Leave-supporting Daily Express (‘Has this lefty think tank found a real solution for Britain?’, they asked). Our own view is that it represents the least-worst version of Brexit, but it is unquestionably inferior to membership. Retaining the right to diverge is no match for making the original decisions. It bakes in uncertainty as to whether the UK would diverge in future that makes this country a less attractive destination for investment. The rest of the world thinks our current deal — in the EU, out the Eurozone, and exempt from Schengen — is unbeatable.

Neither should anyone be under any illusions that it would be easy to negotiate. Lining up the benefits and burdens, the rights and obligations would be incredibly complex. Sophisticated mechanisms will need to be created. At every stage, the EU will have a strategic imperative to ensure that the UK does not have a better arrangement outside the EU than in it. Given the Brexiteers’ belief that they can have their cake and eat it, it would face continuous accusations of being tantamount to ‘punishment’ and betrayal.

The new arrangements would also require new institutions such as a UK Court of Justice and a UK supervision authority. As an international agreement, these would, of course, need to be multilateral with representatives from the UK, EU and neutral countries. The relationship with the European Court of Justice and the EFTA Court would need to be sorted out too. As a result, such new institutions would be heavily contested by Brexiteers who would claim that they were somehow membership of the EU by stealth or a ‘backdoor’ role for the European Court.

All of this would require a busy legislative programme that goes beyond the withdrawal implementation bill. The ERG would fight it every step of the way. So Labour would need to decide whether it would support the legislative programme brought about by its own soft Brexit deal. Bizarrely, that might mean the locus of opposition to Brexit shifting from the opposition benches to the government’s own side.

Moreover, given the enormous complexity of the negotiating task, there is no way that it could be concluded by the end of 2020, just 18 months after the government says it wants to leave the EU at the end of June 2019. So in autumn next year, parliament will need to decide whether to extend the transition (at the cost of around £1bn a month) or to enter the backstop (cue total meltdown on the government benches). It will be a mammoth political fight.

That’s why it is delusional to think that the national conversation will ‘move on’ to the NHS, child poverty, or housing anytime soon. Quite aside from the fact that leaving the EU is bad for Britain, the key assumption of such a political strategy — do a deal with May, stop talking about Brexit — is hopelessly unrealistic. The next three to five years of British politics will be dominated by Brexit no matter what. Everyone needs to adjust to that reality and stop kidding themselves it will be otherwise. With a possible recession on the horizon, the battle over Brexit will only intensify — with Remainers saying it is a consequence of leaving the EU and Brexiteers claiming it is because of the nature of the deal.

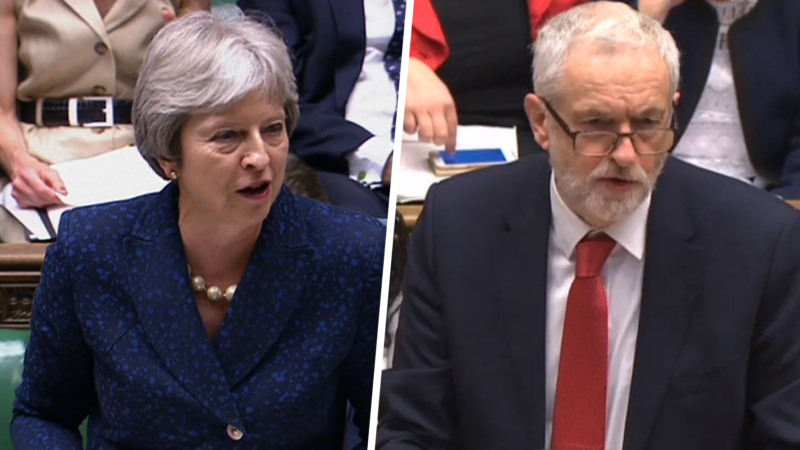

This may all be a moot point. It appears highly unlikely that a compromise agreement can be reached between the government and the opposition. Last night it emerged that the government was unwilling to make any changes to the political declaration, thus rendering the whole process a colossal waste of time. It looks more and more like a ruse to spread the blame around and to try to convince the EU that the government had a plan that would enable a further extension to the Article 50 negotiating period.

The strategic intent of the government’s deal is economic divergence. The strategic intent of Labour’s plan is economic partnership. It is ludicrous to think that the fundamentals of these positions can ever be properly reconciled. Indeed, the government’s acceptance of a customs union through the backstop (ignore the name, in the absence of a known solution to the Irish border, it’s the default not an insurance policy) already illustrates what a dog’s breakfast the current deal is. A customs union must be joined with regulatory alignment to achieve frictionless trade. At that point, leaving the EU becomes largely pointless. So this only answer to ‘why are we doing this?’ will be because we had a vote in the summer of 2016. With Theresa May having already agreed to step down this summer, if a deal can be reached, the only leader defending it at the time of the next general election will be Jeremy Corbyn.

More from LabourList

‘Ukraine is Europe’s frontier – and Labour must stay resolute in its defence’

Vast majority of Labour members back defence spending boost and NATO membership – poll

‘Bold action, not piecemeal fixes, is the answer to Britain’s housing shortage’