Below is the full text of Tom Watson’s memorial lecture marking the 25th anniversary of John Smith’s death.

Thank you. Dianne, thank you for that generous introduction. I want to pay tribute to your long service to the Fabian Society, to the Labour Party, and to our work in the House of Lords. Also – to your work as a historian of our movement.

I doubt there’s anyone here who hasn’t read Dianne’s book ‘Fightback’ about how a group of grassroots Labour activists and trade unionists organised to save the Labour Party in the 1980s. But even if you have read it, read it again! Because it reminds of us two important things – one, that the path leading to Labour’s victory in 1997 was very long, and didn’t start in 1994.

And second, the way you win is through organisation as well as ideas. Dianne, there’s a lovely quote in your book: ‘without organisation, politics is pleasant but its only poetry’. I think I agree with most of that – not sure about the ‘pleasant’ part. Dianne – thank you.

Before I start I also want to pay tribute to Baroness Elizabeth Smith, John’s wife, who we are honoured to have here with us tonight. Elizabeth, we owe you a debt of gratitude for your service to the Labour movement and for all you have done to keep John’s legacy alive. And also for the public service you have given over many years, both as a patron of the Arts and as the force behind the John Smith Memorial Trust and Fellowship Programme, which now has a remarkable network over 500 alumni from 20 different countries, most from the former Soviet Union.

I know that as a fluent Russian speaker you have a lifelong interest in the region and the programme is testament to that passion. I hope you know that you, Sarah, Catherine and Jane were all in our thoughts and prayers over this anniversary weekend.

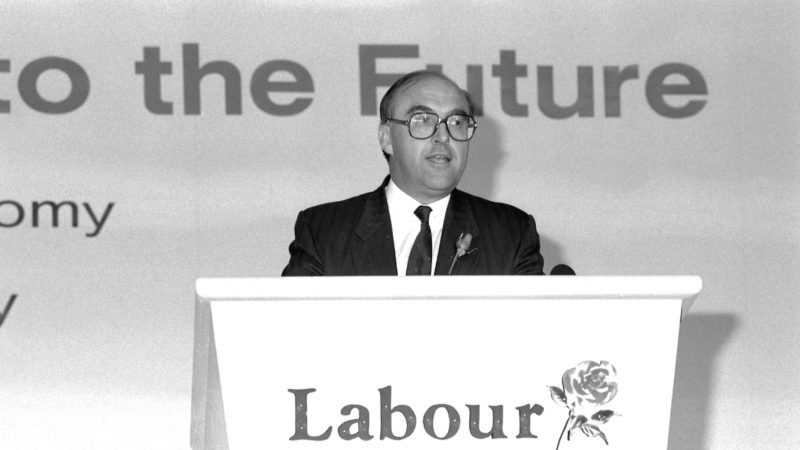

It is a quarter of a century since we lost John Smith, taken at the age of 55, on the brink of bringing Labour into office after nearly 20 years in the wilderness. We have come together this evening to celebrate, to commemorate and to reflect; to see old friends and recall great times. It is a real privilege and a genuine honour to be giving this lecture. I am grateful to Andrew Harrop and the Fabian Society for hosting us.

I was a young man when John Smith died. I knew him, as well as a junior staffer at the party headquarters could know the leader. But ask anyone who worked with him, many of whom are here this evening, and we will tell you the relationship was more than one of dutiful subservience.

We loved him. We had faith in him. We believed in him. Those qualities that the British people so warmed to, and grieved when he died, when strangers wept in the streets, and brought flowers to the steps of 150 Walworth Road, were even more apparent up close. His warmth, his intellect, his humour, his determination and above all his values.

I was there on the night of the European Gala Dinner showing guests to their tables. The now councillor Claire Wilcox and I walked him to his car at the end of the evening and he kindly autographed our programmes. The last line of his speech that night was ringing in our ears –‘please give us the opportunity to serve our country. That is all we ask.’ And that, as we know, was the last speech he made.

Although I cannot claim the close friendship enjoyed by some here tonight, I am going to call him ‘John’ for the rest of my remarks, out of loyalty, love and respect. I want to look at four areas of his life and works this evening, and see what the lessons are for us, 25 years on.

First, I want to look at his moral compass – the things John thought that mattered, the values he espoused, and the strength he drew from them. Second, I want to look at his internationalism. Third, I want to look at his belief in constitutional reform and the devolution of power. Fourth, I want to look at his political method, and the way he conducted his politics.

John was a Christian. I think it is sometimes hard for people without faith to fully comprehend how important it is for people with it. Faith is the beginning and the end of everything, transcending day-to-day concerns, and providing a set of guiding principles for life.

He said in a speech in 1992, ‘the second commandment calls upon us to love our neighbours as ourselves. It does not expect human frailty to be capable of loving our neighbours more than ourselves – that would be a task of saintly dimension. But I do not believe we can truly follow that great Commandment unless we have a concept of concern for our fellow citizens which is reflected in the organisation of our society.’

That last line provides the bridge between the personal and the political. For John saw in Christ’s teachings an imperative to act, to do, to speak up, to stand up, to serve. He joined the Labour Party in 1955, aged 17. He first stood for Labour in the 1961 by-election in East Fife, coming second to Colonel Sir John Edward Gilmour, the 3rd Baronet, who was – unsurprisingly – the Conservative & Unionist candidate.

John’s Christianity propelled him to Christian Socialism, and as such placed him firmly within the Labour Party’s traditions. Our founder Keir Hardie stated many times that his socialism ‘derived more from the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth than from all other sources combined’. And as the excellent History of Christian Socialism by my colleague Chris Bryant reminds us, Christian Socialism has always been part of Labour’s DNA.

Our socialism, as Harold Wilson famously told the 1962 Labour Party conference, owes more to Methodism than to Marx. Of course, the Labour Party has been home to people of no faith and every faith, and all are welcome regardless. But the role of Christians in Labour has been to create a British version of socialism, rooted in values and ethics, not ideology and dogma. We have dodged the mirage of Marxism, but also the false prospectus of ideology-lite centrism.

John’s concern for the poor and vulnerable, his hatred of oppression and injustice, his vision of fairness and equality, these flames burnt no less fiercely in his breast than the self-styled revolutionaries and purists. The difference was his inspiration was practical not academic, socialism as a lived experience not a theoretical construct.

He believed, in his great phrase, in the extraordinary potential of ordinary people. His values drove him, and he saw elected office as the means to put values into action. That’s why the John Smith Centre set up in his memory, which promotes trust in politics and public service, is such a fitting tribute to him.

The research and advocacy work the centre does encourages the next generation of representatives and champions the highest standards in public life. Although based at the University of Glasgow, the centre aims to be UK wide, just as John was a truly UK wide politician. I was delighted to hear Kezia Dugdale, former Scottish Labour leader – who is here tonight – will be taking the helm as Director later this year. I know she will be fantastic guardian of the centre and of John’s legacy.

In December 1992, John established the Social Justice Commission under the chair Sir Gordon Borrie to map out a socialist policy for the country. It reported after his death, and formed the bedrock for the radicalism of the first Labour term after 1997.

The report stated ‘the UK need not be tired, resentful, divided and failing country it is today’ and set out social and economic policies to spread opportunities and life chances, to end poverty and disadvantage, and to create an economy working for every citizen in every community in every part of the country.The cornerstone was the national minimum wage, the fairest, simplest and most equitable way to lift millions out of poverty.

As with most progressive reforms, it is hard, looking back, to imagine the controversy surrounding the national minimum wage. Not just the economically-illiterate Conservative frontbench claiming it would cost millions of jobs, but also from large sections of the trade unions who felt it would undermine collective bargaining, and drag wages downwards, with the exception of the much-missed Rodney Bickerstaffe and NUPE.

John saw that the national minimum wage would be fair and efficient, and that a Low Pay Commission would take the day-to-day politics out of it, and of course history has proved him right. John always believed that economic strength and social justice were not enemies but go hand in hand. He set this out in the John Mackintosh Memorial lecture he gave on May Day 1987, saying:

“Prosperity, broadly defined as a steadily increased standard of living in an efficient and productive economy, is not only consistent with a socially just and caring society, but that in an intelligently organised community, prosperity and social justice mutually reinforce each other.”

When we look more broadly at the achievements of the Labour governments elected in 1997, we can see more continuity with the politics of John Smith than might be thought at first glance. Let me take the issue of child poverty – something close to John’s heart and close to all our hearts. New research published a few months ago by the Resolution Foundation, shows that the Labour government was much more redistributional and had a far bigger impact on child poverty than most people realise.

Taking account of past under-reporting of benefit expenditure and fiscal transfers to the poorest families, the Resolution Foundation now estimates that the Labour government’s target of reducing child poverty by a quarter by 2004 was met and not missed, as was assumed at the time. They also estimate that the target of halving child poverty by 2010 was almost reached, despite the financial crisis, and not missed by a wide margin as has been assumed up until now.

These findings show that the achievements of the Labour government were greater than we first thought and that they are rooted in the Labour tradition that went before, epitomised by the words, deeds and values of John. I’d go further – and say that Labour’s proud record on redistribution is a direct consequence of John’s decision to establish the Commission on Social Justice in 1992.

This was John’s socialism – practical, rational, radical but real. And more – socialist values are not the preserve of some select group of true believers, they belong in the hearts of everyone across our broad church. No-one has the monopoly on social justice.

Secondly, I want to look at John’s internationalism. Because of his values, John believed in solidarity and cooperation not only within the nation, but between nations. And like so many of his generation, brought up in the aftermath of the war, he placed great store in the mighty institutions that Labour helped to create from the ashes of World War Two, particularly NATO and the United Nations.

John supported Britain’s independent nuclear deterrent, and was always prepared to argue, politely but with great conviction, against those arguing for unilateralism. He began his 1993 conference speech as leader with a condemnation of apartheid and a message of support to Nelson Mandela, joining the millions across the political spectrum who opposed apartheid and helped to bring it down.

But on Europe, he was at his most passionate and committed. He saw our future as part of a European project, and famously was prepared to rebel against the party leadership to demonstrate his commitment, alongside 68 others in October 1971. It is worth reflecting that John had been a Member of Parliament for a matter of months, but was unafraid to blot his copy book with the Labour whips so soon into his career.

In a speech in July 1971, he told the House ‘as a democratic socialist I believe … that economic forces must somehow be brought under popular control and be fashioned towards social and political ends which the people determine. If we do not enter Europe we shall not be in a position to control them…’

His pro-Europeanism shone like a beacon for the rest of his life, even until the European gala dinner when he appeared for the last time together with the guest of Honour Michel Rocard, former French Prime Minister and Leader of the French Socialist Party. He was proudly European, and led a party fully committed to the social chapter of workers’ rights, and the single market for goods and services.

As Shadow Chancellor, and as leader, John saw the Tories’ disarray over the Exchange Rate Mechanism and the Maastricht Treaty, and their growing Eurosceptic rebellion, as the opportunity to go onto the attack – highlighting divisions within government, dislocating the Tories from their reputation for economic competence, and at the same time shoring up Labour’s pro-European position, arguing for the progressive benefits of the Social Chapter.

Were he leader today, I have no doubt he would have forensically deconstructed the government’s position, whilst conceding no ground to the nationalist ‘Leave’ argument. He saw anti-EU sentiment, whether of the right-wing independent trading nation variety, or the left-wing ‘socialism in one country’ variety, as equally wrong-headed.

And had John still been with us he would have provided a strong counter narrative to the anti-EU sentiment that set in and festered for the two decades leading up to the 2016 referendum. And I think that were he here now, to witness the great damage this process is wreaking on our country and our public debate, he would have taken a stand very similar to that of his Deputy, Margaret Beckett, and backed a People’s Vote as a way out of this destructive mess.

What can we learn from John’s internationalism? I suppose the importance of strong international alliances, trading blocs, and global institutions as a counterweight to rapacious globalisation. And in a world with growing numbers and strong-armed populist leaders he would have restated the case for international diplomacy in its classic sense.

John exemplified the difference between patriotism and nationalism. He was proud to be Scottish, but never fell into divisive, narrow nationalism. He wanted devolution but never separation. That narrow nationalism he abhorred is set to dominate these upcoming EU elections.

Farage and his far right contemporary, Stephen Yaxley-Lennon, are trying to speak for Britain and define our country. John would have seen this plastic patriotism for what it was and exposed them for what they are – base nationalists of the nastiest kind, the ultimate cynics, playing on fears and lies.

We must not let this corrosive far right sentiment, posing as patriotism, win. I know many Labour supporters are not happy with the position we have taken on Brexit. But I urge those wavering to think about what is at stake here. There are only two forces that can triumph – that nasty nationalism of the Farage Brexit Party, or the tolerant, compassionate, internationalist, outward looking patriotism of the Labour Party.

That’s who we as a party were under John Smith and it’s who we are now. So I ask all Labour supporters, please: don’t stay at home. Don’t put that cross elsewhere. Don’t let them win. We’ve got a week and a half to defeat the intolerance and fear of the far right in the immediate battle facing us. But we also need to think about how to do it in the long term.

So thirdly, I want to talk about John’s belief in constitutional reform that paved the way for huge changes under New Labour that redistributed power away from Westminster. In his famous 1993 Charter 88 lecture he promised a “new constitutional settlement, a new deal between the people and the state that puts the citizen centre stage”. It was that speech that set Labour on a course to create the Human Rights Act, the Freedom of Information Act and Devolution.

John was right that Scottish devolution was unfinished business, and the creation of the Scottish Parliament and Welsh Assembly was his legacy. He also said English devolution was unfinished business – it still is. Finishing that work is part of defeating the forces of Farage and Tommy Robinson.

The longer term struggle to win back the hearts and minds of people in England, who feel left behind and ignored, can only be achieved through a radical shift in power and returning control over their own lives. It’s not good enough for Theresa May to talk of taking back the power from unelected bureaucrats in Brussels only to return it to unelected Bureaucrats in Whitehall.

It is my strong view that John would have understood that for the English Midlands, and the English North, regional devolution would be the only way that the people in those areas can control their destinies.

The fourth thing I want to talk about this evening is John’s political method, how we conducted himself, how he did his politics. He left behind scores of friends and admirers and even the group “the radical ramblers”, who used to walk with John up the Scottish Munros, and who have met for a John Smith memorial walk each year since his death.

If you read the Benn Diaries, or any other memoir of the period, you will have to look very hard to find a contemporary willing to denigrate John. John worked closely with Tony Benn when they were both ministers, and they got on well despite political differences.

And not just Benn. John Smith sought out common ground, believed in dialogue, listening and learning from others. Sometimes, as John Major recalled, these meetings were conducted over tea – sometimes not tea. But he was respected by all, and his decency in his political dealings shone through.

That is not to say he was a soft touch, nor did he let up on his attacks on the Tories. He deployed that cheeky grin, the waspish, witty, forensic skills developed at the Glasgow University debating society, and at the Bar, to wonderful effect in the Chamber.

Many of us here tonight will remember his brutal rendition of the Neighbours theme tune in attacking Nigel Lawson who was being undermined by Alan Walters, Thatcher’s chief economist. Or when he cut down John Major’s premiership saying “as the man with the non-Midas touch is in charge. It is no wonder that we live in a country where the Grand National does not start and hotels fall into the sea…”.

John believed in Parliament as the place to effect change. He was at ease at the Despatch Box, preferring it to the soap box. When his time came to stand for Leader of the Labour Party in 1992, the scale of his triumph reflected the warmth and esteem in which he was held.

John was elected Leader of the Labour Party with the biggest mandate of any Labour leader – 77% of Labour MPs, 96% of the affiliated unions, and 98% of party members, making an overall total of 91%. (the second biggest, of course, was Neil Kinnock’s victory over Tony Benn in 1988, when Neil secured 88.6% overall.)

As Leader, with Margaret Beckett as his able deputy, John began the process of policy-making and reform. He was lucky to have an elected shadow cabinet, chosen by the most sophisticated electorate in the world, the Parliamentary Labour Party. In the 1992 shadow cabinet elections, the top ten included Gordon Brown, Tony Blair, Robin Cook, Mo Mowlam, and Chris Smith.

In the 1980s, the narrative had taken hold that Labour was compassionate but incompetent, and the Tories were cold-hearted, but efficient, and John’s triumph was to dismantle the Tories’ claim to competence, and at the same time re-establish Labour’s credibility on the economy – that’s what the ‘prawn cocktail offensive’ was all about, and the iron law that spending pledges should not be showered around like confetti, without the demonstrable means to fund them.

This economic credibility, painstakingly constructed, was the foundation of Labour’s landslide in 1997, and John was the central figure in building those foundations. In his 1993 conference speech, John framed the political argument as a ‘choice between Labour’s high skill, high tech, high wage economy, and John Major’s dead-beat, sweatshop, bargain basement Britain.’ True then, still true today.

I’ve mentioned the Social Justice Commission as the bedrock of New Labour. John’s other landmark as Leader was the introduction of OMOV, empowering tens of thousands of party members to choose their candidates for the first time.

John Prescott’s speech gets some of the attention in histories of this momentous conference decision. But of course, speeches don’t win conference. It comes down to mathematics. Behind the scenes, John’s supporters such as Hilary Armstrong were strong-arming the union delegations, in the end persuading nine unions from the AEEU to the RMT to back the Labour leader.

The crucial decision was by the MSF delegation to abstain – by 19 votes to 17 – a few hours before the vote. And I wielded my own block vote at that conference, casting 8,000 votes for OMOV as the Chair of the National Organisation of Labour Students.

After John’s success, the Leader of the T&G Bill Morris said ‘we won the argument’. But John had won the votes. As LBJ famously said, the first rule of politics is being able to count.

OMOV triumphed because John was trusted as a supporter of the unions and working people. When so many of his friends defected in 1980 to the SDP, John stayed, like Roy Hattersley, one of the very best of my predecessors as Deputy Leader, and other members of the social democratic and democratic socialist wing of the party. John said at the time it was because he was comfortable with the unions, and Owen and the rest were not.

It reminds us that the revival in Labour’s electoral fortunes, leading to the 1997 landslide, did not begin with advent of New Labour. Labour’s landslide did not come out of a clear sky, the foundations were laid in the 1980s and the 1990s, and John Smith should rightly be credited for his central part, and the formative role he played in the careers and political development of the leaders that came after him.

And once Labour was elected, rather than being a break with the Labour tradition as perhaps some of its more zealous advocates claimed, and its critics have been only to eager to claim, the many achievements of the Government from 1997 to 2010 place it firmly within the Labour tradition and were based on policy commitments made during John’s leadership.

John’s method, then, was conciliatory and respectful, but unwavering on points of principle, and courageous in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds. Above all, it was decent, and his decency shone through in all his dealings. John belonged to a Labour tradition, rooted in the trade unions and the churches, in ethical values, rooted in communities.

When former colleagues left the Labour Party in 1980 to form the Social Democratic Party, he didn’t waver for a moment. These were the people closest to his views on Europe, on NATO, on the economy, and yet his loyalty to the Labour Party and its people transcended the lure of the SDP and its glitzy image. John later said in a newspaper interview ‘I was scandalised by their behaviour – dreadful and disloyal.’

In his biography, Andy McSmith makes another important point – the SDP, like the Bennite Left, was an English phenomenon. The politics of Scottish Labour, of Airdrie and Coatbridge, were distinctly different from Hampstead, Holland Park or Limehouse. John was unbothered with scrapping Clause IV when some suggested it because the theology of the words didn’t concern him. What mattered was the deeds that are needed to transform society.

Despite OMOV some criticised John for not going far enough with modernising the Labour Party. Wherever you stand on that modernisation debate of the time, few people do not believe that a John Smith-led Labour Party would have won the 1997 general election with anything other than a good working majority. The path to victory would have looked and sounded different, but the end destination – Number Ten – would have been the same.

So much has happened in 25 years. Three terms of Labour government have come and gone. Labour has elected four Leaders since John’s death. We’ve seen great changes to our economy and society, with a technological transformation changing all around us. We’re struggling with the crisis over Brexit.

Some of our newer members may find it easy to forget John Smith, after all he was Leader for only two years. But to do so would be a huge mistake. Because if we forget our past, and the heroes who shaped it, we lose our own ability to shape our own destinies. If we fail to learn from past lives – the values, the words and the deeds – of those who came before us – we are doomed to repeat the mistakes of the past.

My plea today is that the values John Smith embodied should not be remembered simply with nostalgia, but as a lodestar for how all of us now in public life should conduct ourselves and approach the new challenges we face.

These values stand as an affront to the intolerance, sectarianism and prejudice poisoning so much of our contemporary politics. It is the job of all of us – especially those of us granted custody of the Labour Party today – to ensure this ugliness does not prevail.

So it is right that we should celebrate the life of John Smith on the 25th anniversary of his death. But more – we should remember his decency and courage, his warmth and his wit, his conviction and his values – at other times too; when we are tested, when we are tired, when we doubt ourselves, when we lack inspiration.

John is with us, speaks to us, guides us, inspires us, and reminds us that the highest and most noble ambition is to serve the people. The opportunity to serve – that is all we ask.

More from LabourList

‘A third way approach is needed to protect children online’

‘Lammy’s jury trial cuts risk worsening racial bias in justice system’

‘Is there an ancient right to jury trial?’