Jeremy Corbyn’s announcement that a future Labour government would no longer pursue social mobility, but would focus instead on social justice for all, was met with a far bigger storm than his team likely imagined. A commitment to replace the Social Mobility Commission with a Social Justice Commission, which in some ways merely represents an evolution in thinking, targets and remit, should have been reasonably uncontroversial, at least within Labour circles.

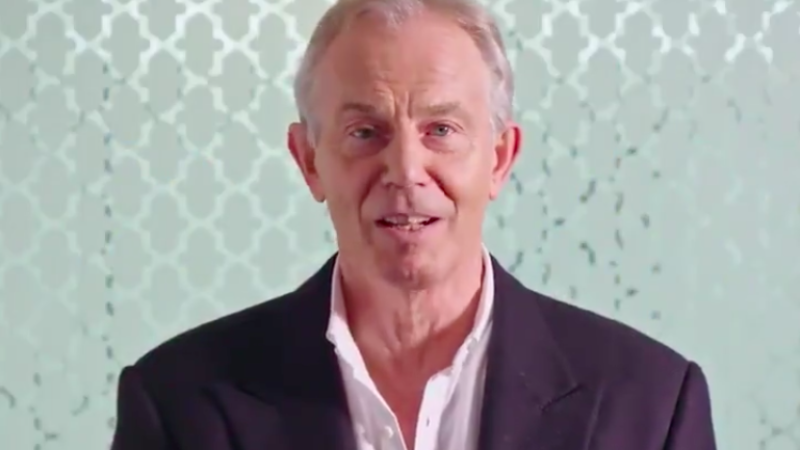

Not so. Corbyn’s apparent elision of New Labour with Margaret Thatcher did not go down well – not least with Tony Blair himself, who shared a robust video defence of his record via his think-tank’s Twitter account. One particular line in Corbyn’s speech about a long-term lack of interest in inequality seemed to touch a nerve.

Tellingly, for the inevitable exchange of partisan absolutes that followed, Blair’s video largely failed to address inequality, conflating it with social mobility and shifting attention to New Labour’s undeniably positive record of investment in public services. However justified Blair and his supporters may be in mounting a defence of New Labour on those grounds, this misses the point at hand.

It’s a matter of recorded fact that overall income inequality grew under New Labour. In the video, Blair prayed in aid the “respected Institute for Fiscal Studies”, but it was the same IFS that reported the increased gap between rich and poor in the period 1997-2010. A 2013 report went further, suggesting it was “much less clear that Labour took a strong view on the appropriate level of inequality within the top half of the income distribution”, going on to cite Peter Mandelson’s infamous “intensely relaxed” line.

Such criticisms are nothing new, either – Ed Miliband spent several years as leader saying similar things about inequality. So while it’s entirely understandable for New Labour figures, as well as sympathetic members and supporters, to want to defend the record of those years in office, there needs to be greater willingness to accept criticism where it is justified.

This is not to say – and crucially Corbyn and others haven’t said – that everything those Labour governments achieved doesn’t matter. As Blair rightly points out, during New Labour’s term in office over a million children and pensioners were lifted out of poverty, investment in public services was at record levels, and, according to an OECD report that he cites, the UK experienced the largest rise in social mobility of any wealthy nation. These are no small achievements. I’ll let Gordon Brown take it from here.

When people say there is no difference between a Labour Government and a Conservative one… pic.twitter.com/wBMSyP2DrR

— Tides Of History (@labour_history) August 7, 2018

This is where Momentum got it wrong. The Corbynite organisation claimed, in response to Blair’s video, that the legacy of the former Prime Minister would ultimately be austerity. Even if light-touch regulation of the financial sector exacerbated the UK’s vulnerability to the financial crash of 2008, and even if Blair himself was quick to endorse the coalition’s programme of deficit reduction, austerity was not the inevitable consequence of New Labour’s policies – it was a political choice by the Tory-Lib Dem coalition.

It is – or should be – possible to be both complimentary of New Labour’s successes and reflective on its shortcomings. To watch Blair’s video and be proud, as Labour people, of all those governments achieved for working people. And to hear Corbyn and Miliband rightly stress the need for a much-increased focus on inequality without becoming overly defensive. It’s a shame that so much effort has gone into trying to make this a binary issue.

More from LabourList

‘As metro mayors gain power, Labour must tighten political accountability’

Letters to the Editor – week ending 22 February 2026

‘The coastal towns where young people have been left behind by Whitehall’