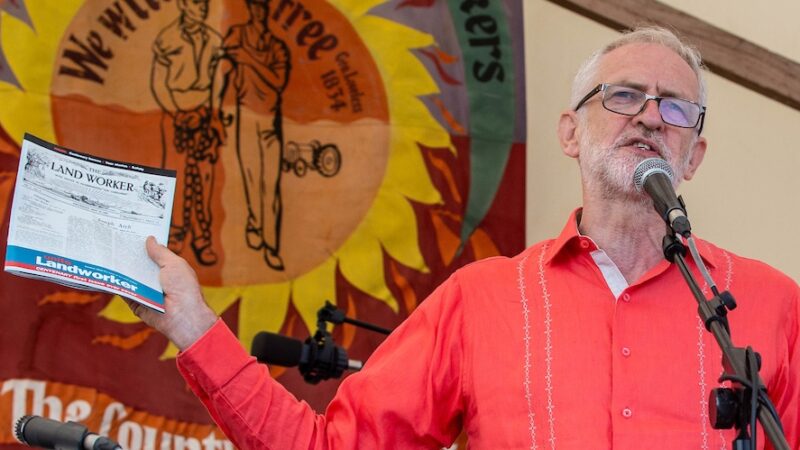

The trade union movement is known for what some might see as a rosy, nostalgic view of our past. But the stories of those who have worked on the land are far from nostalgic, as trade unionists earlier this week discovered at a packed fringe meeting to celebrate 100 years of The Landworker journal.

Rural and agricultural workers are an often overlooked and undervalued part of our trade union family. Many still face the same issues of low pay, job and housing insecurity as they did a century ago. The battles for justice, fairness and equality still rage on.

“The Landworker represents the outward and visible sign of the political and spiritual strength of the British agricultural labourer: it is the birth of a new power; the creation of a mighty potential force,” its opening editorial reads.

“Liberty, equality and fraternity”, “peace, retrenchment and reform,” “justice, unity and goodwill”. These are the forces; this is the faith which will be the guiding principle of this newspaper. That carried to their logical conclusion they mean revolution, we do not hesitate to say.”

Revolution indeed, nothing less. These inspiring words are from the man that founded the Eastern Counties Agricultural Labourers & Small Holders Union in 1906, later known as the National Union of Agricultural Workers, and now part of Unite the Union. That was George Edwards, a farm labourer’s son, whose vision brought about The Landworker.

At the beginning of the war, the union had 2,583 members. By 1919, as the soldiers returned from Flanders Fields to the fields of home and hope, membership topped 170,000 – the result of constant union campaigning for higher wages and better conditions during the war years.

Many returning were lonely, disillusioned and irreversibly traumatised – lost in a world that had little understanding of what they had suffered. So it was time to join the union, and they did so in their droves, demanding a better life after years of wartime sacrifice. And into this new world, with 152 days lost to strikes, Landworker was born, supporting activism, supporting rural workers.

Landworker captured the radicalism at home and abroad during this period and tempered it with realistic and peaceful goals. ‘Revolution’ meant “the revolution of mind, not brute force; of the saving of men’s lives, not of the bloody slaughter of their bodies; of economic, national, and international goodwill”.

Landworker continues: “That a man has a right to live, not only decently, but with leisure to cultivate the powers of his body, mind and soul, equally with others of whatever class; that the land was made for all, and not for the few; that essential industries shall be worked for the good of all; that the aged and infirm shall be cared for by the State; that women are to be placed on an equality with men.” Surely this is the very revolution that 100 years on we are still fighting today.

Over the last century, Landworker has indeed been part of this revolution – sometimes quietly, sometimes roaring like a lion – always fighting for the rights of workers many take for granted. But what of the situation facing our members today? Landworker has just reported on the impact a no deal Brexit will have on our food industry – it’s nothing short of a complete farmageddon.

If no deal isn’t taken off the table, then the tables of this nation will be empty: food rotting unpicked in fields or aboard lorries not going anywhere, while livestock farmers facing impossible tariffs protest by blockading roads with their sheep and cattle. Industry specialists warn that half of all farms could fail, with overall profits for the sector sliding by 18%, or £850m a year.

At best, we only have seven months’ worth of UK-produced food before we have to rely entirely on imports. Currently the average shopping basket will go up by 7%. And for any farmers wishing to sell their produce overseas, they are looking at paying extortionate WTO tariffs, like skimmed milk at 74% and beef carcasses at a whopping 92%. Who can afford to run a business like that?

Britain’s food industry employs 450,000 people, with over four million more working in the food supply chain. It’s 17% of all UK manufacturing. Everyone needs food, right? So why is the true situation in food production and farming such a secret?

Farmers employed thousands of EU seasonal and migrant workers to pick their produce – often paying them as little as possible, working them in long shifts and housing them in trailers and sheds.

Who will pick our food now? Scientists have developed a new ‘Robocrop’ fruit picking robot – but unfortunately it takes over 20 minutes to pick one raspberry and any crushing avoidance can’t be guaranteed. Some clever farmers have come up with a really progressive idea: make Universal Credit claimants and disabled people pick food. It’s an idea some are taking seriously.

Where are the young farm workers? Where are the young people willing to work in field and forest? Where are their incentives? When the Tories took away the Agricultural Wages Board in England, they abolished the skills-related bands and reduced the lowest down to the national minimum wage. Long hours, hard work, low wages, no guarantees. What young person wants to go into that? And they don’t.

What can be done? In the short term at least, the answer is simple. We need a Labour government. But to win, Labour also needs to secure the votes of those living in rural communities, who by and large believe that Labour does not represent their interests.

In 1945, Labour won its first majority government – by a landslide – and this was in no small part down to Labour connecting with rural workers. We need Labour to do this again – to ensure rural workers have a government that speaks for them too.

George Edwards gave us a ‘revolution’ – he gave us The Landworker – a journal for members which has lasted 100 years. And it’s still going strong. So let us all join the revolution he spoke of 100 years ago, of “justice, unity and goodwill”.

“Rejoice in the great reforms which loyalty to the workers has made possible. Go on still further in the path of human progress and social betterment. The accomplishment of still greater things depends upon you. Be faithful, be comrades to each other, be courageous.”

More from LabourList

Government announce SEND reform in schools white paper

SPONSORED: ‘Industrial hemp and the challenge of turning Labour’s priorities into practice’

‘A day is a long time in politics, so we need ‘action this day’’