Listening last week to our Shadow Employment Rights Secretary, Andy McDonald, setting out the party’s vision on workers’ rights was a rare, unifying moment for Labour: “A Labour government that will restore to every working man and woman the dignity, the respect, and the rights to which they are entitled. Our charter of employment rights will give all working people basic rights that will come into force from the first day of their employment. We will give the same legal rights to every worker, part-time or full-time, temporary or permanent.”

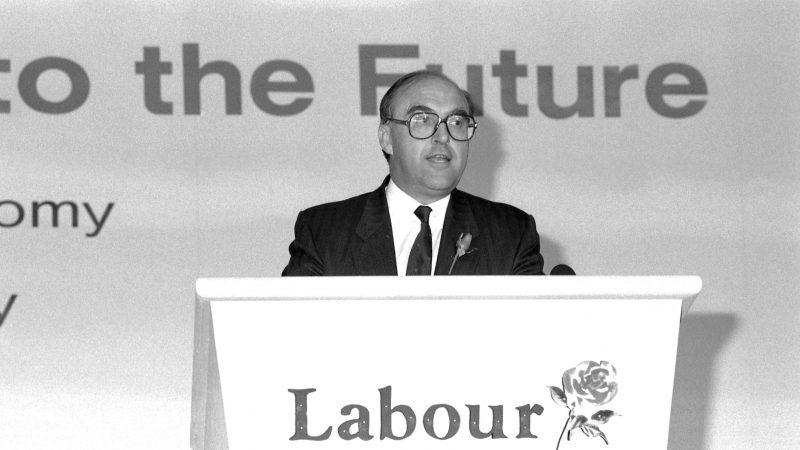

The words above aren’t McDonald’s but those of Labour leader John Smith nearly 30 years ago, giving what would tragically be his final party conference speech. But when McDonald pledged that “Labour will end the bogus system of different employment statuses to give all workers full rights and protections from day one”, the echoes of Smith were clear. When Smith died eight months later from a heart attack, Labour was 21 points ahead in the polls, and the country was deprived of a great Labour Prime Minister. Sadly his successor dumped the charter of employment rights, along with Smith’s commitments to public ownership of the railways and the restoration of the pensions-earnings link.

Smith was not on the party’s left, but neither was he ‘New Labour’. “I joined the Labour party because of its values: the values of democratic socialism,” Smith once said. In that final conference speech, he implored delegates at conference: “We, as democratic socialists, have always believed, that it is the duty of government to match unmet needs with unused resources.” There is much for Labour to learn from Labour’s lost Prime Minister. Smith was criticised by some on the party’s right for not going far enough (he rejected calls to re-write Clause IV) and was condemned by some on the left for his move to one-member-one-vote (OMOV) in party voting (though most on the left now embrace this change).

Speak to those around at the time, and while some decisions were criticised, he had most people’s respect. He made an effort to maintain cordial relations with both the left and right of the party. I recall discussing him with then leader Jeremy Corbyn. When the then backbencher met with Smith to discuss restoring devolution in London, “yes” replied the leader with a smile – “but Scotland first”. It is worth remembering how much of the New Labour agenda that was universally regarded as positive was John Smith’s – not just devolution, but the minimum wage too.

When Starmer, like Smith an ex-lawyer, won the Labour leadership promising unity on a social democratic policy platform, few drew the parallels. It is a symptom perhaps of the party’s lack of political education, and the turnover in its membership, that this wasn’t more discussed. As Starmer has strayed from his winning mandate, so his leadership has faltered. It is clear from back issues of Socialist Alternative that Starmer disliked Neil Kinnock’s leadership, but sadly no readily available record exists of his views on Smith.

Smith had a shadow cabinet that embraced all wings of the party, from Michael Meacher, who had challenged Kinnock alongside Tony Benn only a few years before, to Tony Blair. All of Labour’s most successful leaders have recognised the need for a broad-church approach: Clement Attlee, Harold Wilson, and Smith. If it wasn’t for a heart attack robbing the country of the latter, they would have been the Labour Prime Ministers of the post-war period. Each of those leaders recognised that unity required hard graft to coalesce Labour’s disparate traditions behind a shared project. Wilson’s dictum is apposite here: “The Labour Party is like a stagecoach. If you rattle along at great speed everybody is too exhilarated or seasick to cause any trouble. But if you stop everybody gets out and argues about where to go next.”

28 years on, and after 13 years of Labour government, it is tragic that Smith’s charter for employment rights is even more necessary today than it was when first proposed. But there is more to learn from Smith than that one policy. If Starmer wants to be Prime Minister, he needs to replicate more than Smith’s policy on workers’ rights. He needs to emulate an approach that picked up the party after four general election defeats and genuinely put the party 20 points ahead in the polls.

More from LabourList

‘Are slates helping or harming Labour’s internal elections?’

EXCLUSIVE: Usdaw General Secretary writes to PM ‘frustrated’ regarding changes to Employment Rights Act

Think tanks and MPs call for targeted response as Iran war impacts cost of living