The Forde Report’s been published, the national executive committee (NEC) ballots are dropping, and Sam Tarry is off the shadow frontbench – factionalism is back baby, and it’s good again (awoo!).

Of course, it never really went away. For as long as there has been a Labour Party, there has been factional infighting within it, and Patrick Diamond and Giles Radice’s new book – Labour’s Civil Wars: How Infighting Has Kept the Left from Power (and what can be done about it) – is here to tell us everything we need to know. It offers a clear and fairly comprehensive rundown of the key factional divides and internal fights that have raged in the party over the last century.

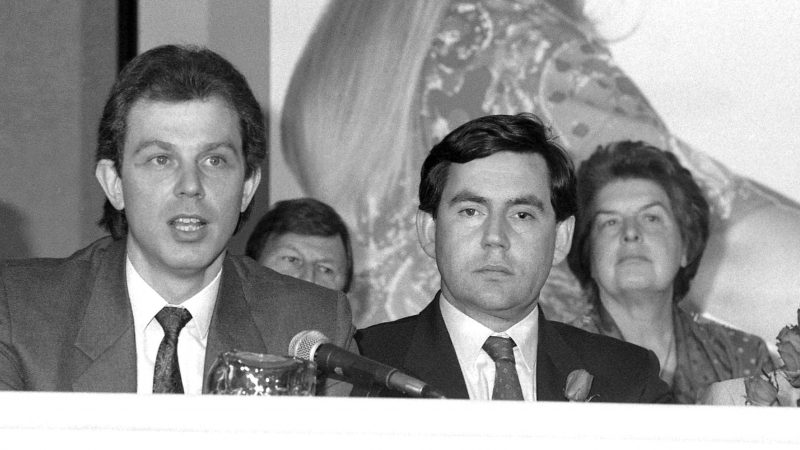

The book kicks off with Ramsay MacDonald, Labour’s first Prime Minister, who was at war with pretty much everyone. We move through Hugh Gaitskell’s acrimonious feud with Aneurin Bevan in the 1950s and on to the multi-fronted clashes of the 1970s, when Tony Benn, Roy Jenkins, Dennis Healey, Michael Foot, Anthony Crosland and James Callaghan vied to lead the party and the country. In the 90s and 00s, we take a look at the fraught and often distrustful partnership between Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, the “rock on which New Labour was built”. The book concludes by taking us up through the internally fractious Jeremy Corbyn years to today.

If you are looking for a primer on who was who (and who they hated and why), this book will provide an able and neatly laid out – if somewhat stylistically flat – guide. What it will not be, however, is an unbiased one.

Patrick Diamond is now director of the Mile End Institute and a politics academic at Queen Mary University of London. Before this, however, he was chair of the National Organisation of Labour Students, director of Progress and latterly a senior advisor to Blair and Brown. Giles Radice was a Labour MP from 1973 to 2001; he is now in the Lords. He is perhaps best known for his 1992 pamphlet Southern Discomfort, which discusses Labour’s need to win in the south of England and how it might do that through a move to a more aspirational politics. Diamond and Radice are both keen and insightful writers on politics; what they write is worth reading. What they are not, however, is unpossessed of politics of their own. They are people of the Labour right, and their book is, basically, a factional history of factionalism.

You can see the worldview of the authors bleeding through at many points. You can see it when they describe Ramsay MacDonald as handsome twice in two pages. You can see it when they talk about how Gaitskell “helped his political cause by coming across as reasonable and courteous”, while asserting that it was “apparent that Bevan and his associates lacked a robust theoretical analysis of economic and social changes in post-war British society”. You can see it when they quote Radice’s “personal diary” from the aftermath of the 1981 deputy leadership race, where he wrote “by beating Benn, however narrowly, Denis Healey has saved the Labour Party”. The book then argues that this was correct, as Healey’s victory “stopped Benn in his tracks”, “broke the hard-left stranglehold on the NEC” and therefore “effectively curtailed” the breakaway to the SDP. “In that sense,” the authors conclude, “Healey really did save the Labour Party.”

You may agree with this, you may not. This isn’t an exact science. There is no way to be axiomatically correct on this topic – your answer probably depends on your politics. There is merit to a factional history of factionalism. I am interested in what Radice was writing in his diaries and interested in what Diamond has to say about it – but there is something frustrating about such an obviously factional account coming with only a quick confirmation in the concluding section that the authors take a “revisionist” perspective. It is worthwhile to know what the revisionist perspective is and how this political tendency views the past. What is on offer, however, is not (as the back cover quote from Dianne Hayter, a telling person to have blurbing your book, would have you believe) a “cool assessment”.

It’s not factionalism when we do it, would seem to be the implication. It is, though, and their book would be a better read and a better tool to understand the party if it were presented as such. The Labour Party has always had factionalism. To a greater or lesser degree, we probably always will. We might as well be honest about it.

More from LabourList

‘What Batley and Spen taught me about standing up to divisive politics’

‘Security in the 21st century means more than just defence’

‘Better the devil you know’: what Gorton and Denton voters say about by-election