This year sees the centenary of the first Labour-led government, and the first government in which a woman – Margaret Bondfield – held any kind of ministerial post, serving as parliamentary secretary to the Minister for Labour. As Labour took office, it was a very different party from that of the pre-1914-18-War years, and one of the main reasons for that was that the majority of its members were now women.

The 1918 Representation of the People Act gave the vote to all men and to women over the age of 30 who met a property qualification, either directly themselves or through their husbands.

As a result, although any woman over the age of 21 could stand for Parliament, about 40 percent could not vote. Thus Ellen Wilkinson, first elected to Parliament in 1924, was unable to vote for herself because she did not meet the property qualification.

In 1914 the Labour Party had been a loose grouping of more-or-less like-minded affiliates, but in 1918 the introduction of individual membership made it a mass membership organisation.

However, although working-class men tended to stick with their affiliated trade unions and exercise their political rights through that route, women, who had much less presence in the trade union movement, joined the Labour Party as individual members very quickly in large numbers. In 1918 there were just 5,000 women members, but within three years this had risen to over 70,000 and continued to grow throughout the decade.

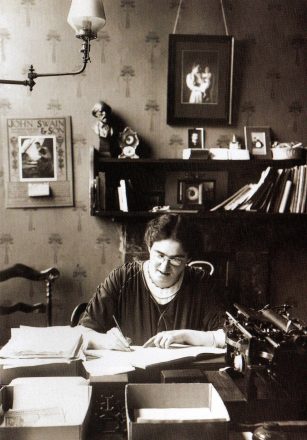

The Women’s Labour League (WLL), an independent organisation of women affiliated to the Party before 1918 (and the last women’s affiliate until Labour Women’s Network affiliated nearly a century later) was absorbed into the Labour Party and its branches became Women’s Sections. As part of the deal, and in the earliest known use of a quota, women were guaranteed four places on the National Executive Committee (NEC). The WLL Secretary, the redoubtable Marion Phillips, became the first National Woman Officer.

To cater for the new women members an entire organisational structure was built to support them. Each region had a Woman Organiser whose job it was to develop women’s sections, provide them with political education and train them for election work. Various bodies were set up to bring women together and to connect them to the mainstream of the movement, and Women’s Conference met annually as a delegate body. Women were also encouraged to stand for public office, although as might have been predicted many found it difficult to find winnable seats.

Perhaps unsurprisingly the sudden arrival of women into the Party with their own structures and conference led to a build-up of tension and disagreement both between women members and the Party leadership, and between women themselves.

Leading men were often alarmed to find that the issues women wanted progressed were not what they thought they ought to be, and that women had demands which were at variance with their traditional roles.

One of the major issues that the new Labour government took on in 1924 was housing. Because poor housing was considered to be (and still is) a major factor in poverty and ill-health, responsibility for it lay with the Minister of Health, John Wheatley, and his Parliamentary Secretary, Arthur Greenwood.

After the War many women had been forced back into their homes by post-war employment policies which had systematically removed them from the workplace in order to accommodate men returning from the trenches.

As talk of ‘homes fit for heroes’ increased, Marion Phillips and Averil Sanderson-Furniss noted in an article in The Labour Woman in 1918 that: ‘The working woman spends most of her time in her home, yet she has nothing to do with its planning. It’s time this state of affairs ended.’

Unfortunately, neither Liberal nor Labour Health Ministers agreed, and Wheatley failed to consult even the most senior Labour women when drawing up his (otherwise rightly praised) Housing Act in 1924. This state of affairs continued for many years; in the 1940s Labour women like Margaret Bondfield were still trying to persuade their colleagues that women might have something significant to say about housing.

A more controversial issue was access to birth control, which many Labour women believed was the key to improving women’s health, decreasing maternal and infant mortality and reducing poverty. However, Wheatley was adamantly opposed to it, even suggesting that if ‘respectable’ women arrived at maternity clinics to find birth control advice on offer they would be put off attending at all.

Both the Parliamentary Party and the NEC backed Wheatley. Marion Phillips was also hostile on the grounds that supporting birth control would be an electoral liability, an early example of the mistaken belief that controversial issues are to be avoided at all costs by parties wishing to be elected.

By the time Labour returned to government in 1929, however, opinion had begun to change. Greenwood became Health Minister with Susan Lawrence as his Parliamentary Secretary and in 1930 local authorities were allowed to offer birth control advice if they wished.

As Keir Hardie had remarked before the War, it was never likely that men would surrender power simply because they were asked. Like many other parts of society, Labour has struggled over the last century to accommodate the full diversity of the electorate it serves.

There is still a long way to go, but the progress the Party has made and is making is at least in part down to the persistence of those first women who joined in 1918 and began to make their voices heard.

This article is part of a series to mark the centenary of the first ever Labour government, guest edited by the Labour MP and writer Jon Cruddas, who has written a new history, ‘A Century of Labour’ (Polity Books).

More from LabourList

‘Someone to bring them together’: The Gorton and Denton by-election campaign from the ground…

Labour ministers, MPs and mayors rally behind PM amid calls for resignation

Scottish Labour leader Anas Sarwar calls on Starmer to resign