Transitions from one governing party to another are rare in recent British history, with power changing hands just twice in the last 40 years. If Labour wins the next general election, 85% of its shadow ministerial team will have never served in government before and the party will not have managed a transition for over 27 years.

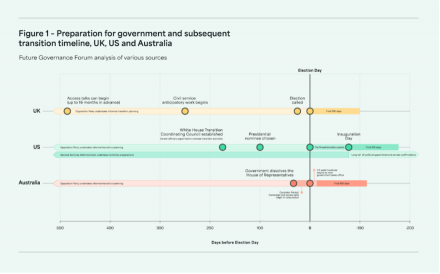

That daunting task is made more challenging still by the overnight nature of UK transitions, in stark contrast to many other democracies. As soon as the votes have been counted, if there is a clear winner then the new prime minister enters Downing Street and starts governing immediately. There is no US-style 11-week gap between election and inauguration.

There are international examples of conservative-to-progressive transitions

Yet a well-managed transition can mean the difference between a new government delivering on its election promises straight away, building momentum behind its programme, or having to spend months recovering from a shaky start.

The stakes are always high at such moments, but are even more so right now given Keir Starmer’s ambition not just to implement a different policy agenda to the Conservatives but to embed a fundamentally different, mission-driven approach to governing into the British system.

That’s why The Future Governance Forum (FGF), a new progressive think tank focused on fixing Britain’s broken system of government, has been speaking to senior figures in the US Democrats and Australian Labor to determine principles and recommendations for an effective conservative-to-progressive transition.

Published today, FGF’s latest report Into Power 01: Lessons from Australia and the United States calls on Labour to look to its progressive sister parties for insights into how to set up an incoming progressive administration to govern well.

Transition is political , so set a clear direction and tone

Transition is not an administrative task with a political flavour; it is an inherently political task. Should Labour win in 2024, its move into power will be a ‘Starmerite’ transition, whether intentionally so or not, because it is being undertaken by this leader and this top team.

This is something Australian Labor strategists sought to make a virtue of by being explicit about it: posing challenging questions to party leader Anthony Albanese about the kind of prime minister he wanted to be, the way he wanted to govern and what a successful first term would look like.

UK Labour should be asking itself those same questions today, so that everyone involved in transition planning knows they are delivering on a clear vision set at the very top. Taking the time to do this now will pay dividends later: as attention and resources are (rightly) pulled more and more into the campaign, it is vital that the transition team can be confident it is delivering on the leader’s wishes and with his authority.

Think first 96 hours as well as first 100 days

Launched today – #IntoPower 01: Lessons from Australia and the United States 🇦🇺🇺🇸🇬🇧

What can UK opposition parties learn from the Biden and Albanese transitions to government ahead of the next election?

⬇️ Read the new report from FGF, or read on… 🧵https://t.co/AMxuUc1ofQ pic.twitter.com/STzj6LGW0K

— The Future Governance Forum (@FutureGovForum) February 28, 2024

Ever since Franklin D Roosevelt established the term almost a century ago, politicians and journalists have fixated on what a new government can achieve in its first 100 days.

That remains a vital milestone, and a transition must include a plan for it, including staffing all departments, policy announcements, major set pieces, overseas trips and media interventions.

But some of those days are more important than others. Members of Albanese’s transition team told us the importance of an almost hour-by-hour plan for the first 96 hours – the “high-risk time”, as one of our interviewees put it – when the new government has maximum political capital but is also at its most inexperienced.

Pick the best people – and establish a ‘beachhead’?

An incoming government has hundreds of roles to fill, and yet in the UK this process is often opaque and informal. This risks an administration that is not representative of the people it has been elected to serve and that cannot identify and hire the very best people it needs to govern well.

In 2020, then president-elect Joe Biden told his transition team he wanted his administration to “look like America”, and they delivered.

While the UK may be some way off having the scale of a US transition operation – including the establishment of ‘talent banks’ on which an incoming government can draw when recruiting – Labour should embed the principles of open, transparent recruitment and ensuring diversity of background and experience when making appointments.

Another lesson from American recruitment that Labour should consider is the establishment of ‘beachhead’ teams: temporary hires who enable a new government to start delivering from the word go and lay the foundations while permanent appointees are being put in place. This could be particularly beneficial given the UK system’s near-instantaneous handover of power.

It is vital Labour thinks about winning power, but also how it would exercise that power

As we inch closer to the next general election, it is vital Labour thinks not just about winning power, but how it would exercise that power in office. The recent experiences of Biden’s Democrats and Albanese’s Labor Party offer valuable lessons for their counterparts here in the UK as they prepare for the possibility of office.

How well Labour handles this crucial pre-election period will determine whether a future government can begin delivering quickly on its election promises, whether it can govern well and effectively, and ultimately whether it can change life for people in this country for the better. Getting it right matters for everyone.

More from LabourList

Antonia Romeo appointed to lead civil service as new Cabinet Secretary

‘If Labour is serious about upskilling Britain, it must mobilise local businesses’

Stella Tsantekidou column: ‘What are we to make of the Labour Together scandal?’