In his last budget before the general election, chancellor Jeremy Hunt proved the rule that this grandstand “fiscal event” is less about economic policy and more about politics. His goals were to improve the Conservatives’ electoral prospects and tie the hands of a future Labour government rather than delivering a long-term plan for the British economy.

One of the key problems for the British economy is short-termism of this kind – and the annual budget is a major culprit in the politicisation of economic decision making.

Conservatives attempting to frame Labour as the party of tax rises

The politics of Hunt’s budget are double layered. Policies such as the 2p cut to national insurance and continued freeze on fuel duty are obvious sweeteners to voters. Abolishing “non-dom” tax status undercuts Labour and seeks to position the Conservatives on the side of ordinary voters. The contents of Hunt’s self-proclaimed “tax cutting budget” was widely anticipated and, predictably, framed in contrast to Labour – a party of “tax risers”.

The tax cuts offered are clearly also designed with the election in mind. They are a short-term boost to some – and probably those voters the Conservatives most want to target – but do little to tackle concerns about the doom loop – failing public services alongside increases to the cost of living.

The scorched earth tactic here is to delay expensive investment. Sticking with a 1% real-term increase in spending on public services is part of the politics. But it has drawn criticism as being a “work of fiction”. The reality is increases in spending on health, defence and childcare mean that wide-ranging cuts to other public services are inevitable.

Not enough focus on public service funding

Hunt’s plan to improve productivity in the public sector is important, but hardly novel. The devil is in the detail.

Crucially, prioritising cash-releasing savings with an inadequate focus on the outcomes of public services – the part that voters experience in their own lives – will reassure few.

This is all a considerable conundrum for a prospective Labour government. A combination of future projected spending cuts and Labour’s own political drive to demonstrate that it is not the party of tax and spend means it has become highly constrained in what it can do.

As far back as 1992, former chancellor Gordon Brown developed a set of fiscal rules to show the party could be trusted with the public finances. These rules governing tax and spend commitments were introduced by the Labour government in 1997 and have subsequently become a firmly embedded Treasury tool. Yet the rules are neither fixed (we are currently on the ninth version) nor immune to political manipulation.

The government is close to breaking its own fiscal rules

We now have a “headroom fallacy” focused on what the government can spend before it breaks its own fiscal rules. The benefits of longer-term investment and economic competence are sidelined in this political game.

Like her predecessors, Rachel Reeves, the Shadow Chancellor, appears cornered by the twin effects of that 1992 budget. She is reluctant to commit Labour to any notable tax and spend policies and is, at the same time, scaling back on any macroeconomic grand strategy because of her commitment to a restrictive set of fiscal rules that Labour regards as electorally so important.

Where then, does this leave Labour given the Hunt budget and the public’s views on the current state of public services?

Labour will face an uphill battle in commitment to cut debt

Labour’s problem is that it is committed to a set of fiscal rules that severely constrain its options. Reeves has said that Labour is committed to reducing debt over the medium term. Government debt is now at the highest level in 40 years and projected to fall by the Office for Budget Responsibility “as a share of GDP in 2028-29 by a historically modest margin of £8.9 billion”.

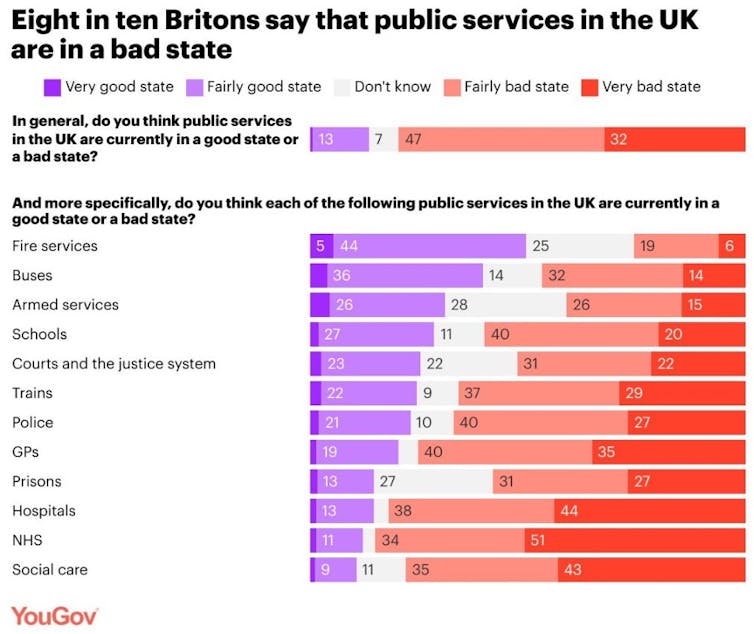

Economic growth projections are fragile. The public spending round estimates cuts in spending for 2025, at the same time a recent YouGov poll suggests 79% of voters believe that public services are in a poor state.

It is difficult to see how Labour can meet voters’ expectations of improvements in public services and, perhaps even more problematically, public sector pay increases, when Labour is committed to fiscal rules which, while politically expedient, make no economic sense. If Labour is to reduce borrowing and not increase taxes, the prospects of increased public spending are limited.

It’s unclear what the Tories think will drive growth

Starmer proclaims the only option for a future Labour government is to improve productivity and grow the economy (echoing both Liz Truss and Rishi Sunak). Yet, like the Conservatives, it is not clear what the driver for growth will be. Overwhelmed by the fear of the charge of profligacy, Labour has scrapped its £28 billion green investment plan, which had the potential of driving an economic renaissance.

In terms of productivity, Britain has fallen behind both its US and European counterparts for nearly 20 years. Its record on research and development investment is poor. Resisting calls to re-join the EU or make any major changes in industrial policy, Labour’s plan seems to be a vague hope that growth will return in its own time. The worry is short-termism and muddling through will once again repeat themselves after the election.

This article first appeared on The Conversation.

More from LabourList

Delivering in Government: your weekly round up of good news Labour stories

‘Outflanked on both sides: why Labour is losing touch with the economy’

‘Labour’s lesson from Denmark: immigration alone won’t save you’