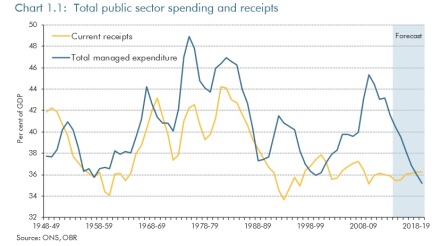

A single graph in a turgid economic document has provided an opening that could enable Labour to change the terms of the political debate. The Office for Budgetary Responsibility’s ‘graph of doom’ shows that George Osborne’s plans for eliminating the deficit will leave Government at its smallest size for 80 years by 2019. The IFS described the planned level of cuts as ‘colossal’. This is not a consequence of austerity. It’s a consequence of George Osborne’s ideology. The graph, in case you haven’t seen it, is below:

There has been little debate about what this level of state shrinkage might mean for the well-being of British society, its social and economic future, or of any of the serious downsides of this approach. The focus has instead been on austerity. This is confusing two debates. There is a different approach to eliminating the deficit in terms of timing, impact on growth, mix of tax increases and spending cuts, and distribution of burden. In the last year or two Labour has moved onto this more realistic territory (‘no cuts’ is just as potentially harmful as ‘nothing but cuts’). This debate over ‘austerity or not’ is rightly being left behind and the focus is now on how and when.

And so the real debate is now upon us: what sort of state do we want and need in order to safeguard the future? We are into the territory of stark choices. George Osborne’s vision, despite the fairly empty rhetoric of ‘long-term economic plan’, is a minimal state focused mainly on welfare spending of various different types. There is an available alternative. That is a state that is there to create long-term social and economic prosperity. This empowering state means that we will collectively have to pay more taxes but it will be better for all our long-term futures. This is a clear ideological divide.

To win this battle Labour can’t simply argue for a bigger state. It will lose that debate. It must argue for a reformed and more effective state (albeit one that will be bigger than the Osborne vision). This different type of state would be 4d: devolved, distributed, digital, and developmental.

It would take a devolution agenda as advanced in Labour’s policy review and give it rocket boosters. To do this it would create two new constitutional innovations. Firstly, it would introduce an act to commit itself to a large-scale transfer of resources (and tax-raising powers) to institutions that are fully locally accountable. The target might be, say, five percent of all Government expenditure to be devolved within five years and ten percent within ten years.

A demand pull mechanism is needed also. Local authorities, groups of local authorities and other locally accountable public bodies could be granted the right to demand full and flexible control of state resources expended locally subject to two light-touch safeguards. These would be top level outcome commitments (eg to increase the skills levels of the area over and above trend) and having clear local accountability measures in place.

Next, Labour should then seek to distribute power differently. Resources and power would be put directly in the hands of citizens. A citizen’s resource would be passed to those who are disabled, have long-term conditions, who access welfare and skills systems. For those who need care, the current system of personal budgets would be greatly expanded.

A new layer of advisers, brokers, co-operative organisations and social enterprises would be supported through devolved institutions to help people make best use of this citizen’s resource. Communities would be able to insist on resources to look after their own environment (including community safety measures) in the same ways that groups of local authorities will be able to demand the same from Whitehall. This distribution agenda is a natural fit for Ed Miliband’s wish to give greater powers and support to people in the workplace.

The increasingly ubiquitous spread of digital technologies makes the sort of support mechanisms needed to spread power in this way possible. These technologies can bring people together so that they can share information and co-operate on a local level. They enable, with proper open data, better accountability of providers for the services they offer. It creates a better platform for interfacing between services and the citizen. It can provide better ways of supporting people with new services – and this is essential to make the spread of citizen’s resource result in better life outcomes for people who rely on services. Devolution, distribution and digital all go together.

Finally, there is gearing the state towards a development focus. This means directing state support to a significant spread of new skills throughout the workforce, new entrepreneurs, investing through devolved financial institutions in high growth potential businesses, and supporting a world-leading science and higher education base. It also means building houses – essential for economic stability and social well-being.

This is what a long-term economic plan looks like. It’s also what a long-term social plan looks like. If Labour’s message going into the election is what we are about is spreading wealth and power, a focus on an empowering state and a less unequal society that is a pretty powerful and compelling vision. It certainly provides a strong alternative to the shrunken welfare-focused state that George Osborne envisages. All of this can be achieved within the envelope of Labour’s current fiscal plans.

It should make a virtue of the difference between the future it would offer and the Conservative vision. There’s no need to be defensive. Ultimately, if people choose the Osborne way or want to focus on immigration then at least the choices have been laid clearly before them. A plan for Government secured upon devolution, distribution, digital, and development together mark a different national future. Trust the people and they might just trust you back.

More from LabourList

‘Ukraine is Europe’s frontier – and Labour must stay resolute in its defence’

Vast majority of Labour members back defence spending boost and NATO membership – poll

‘Bold action, not piecemeal fixes, is the answer to Britain’s housing shortage’