I read Arnie Graf’s piece for LabourList yesterday with some interest. I have to say it struck me as a fairly restrained summation of conditions on the ground but left me a little underwhelmed as to the recommendations. Why? Because I don’t think they go far enough.

My story is somewhat different to Arnie’s. For the last dozen or so years I’ve made a living predicting elections. Over many years it became a requirement of my predictions to anticipate price movements, but also to predict the political weather. One develops a ‘feel’ for these things; I can’t explain it, I just learned what was important and what wasn’t, and how it might affect the future prices on the markets.

After President Obama’s election in 2012 I had the resources to take a break and ponder what I wanted next. I had been asked on many occasions by different people to write a blog on what I did. After some thought I took a punt and wrote a fairly simple blog about data. Boom. I was inundated almost immediately by journalists, academics and political parties interested in my work.

So I was taking on work for representatives of all the political parties. There is only one party I have not had any association with, and that’s the SNP. Somewhat remarkably I was consulted by UKIP for the Heywood & Middleton and Rochester & Strood by-elections. Some months later I found myself on the other side of the fence trying to fend off their challenge in one of those same seats. I’m not betraying confidences here; Labour were fully aware of my work for UKIP.

In November 2014 I was brought into Labour to help in any way I could. I have a wide range of skills I hoped the party might use, and I believed (and still believe) the party could use them. As some of you may remember, I was one of the more vocal critics of the party’s response to UKIP last year; in particular of the view that UKIP were “more of a problem for the Conservatives”. I now know that there were many within the party who not only agreed with me but fought that precise point but failed to make headway.

Those discussions are for another time. I wanted to describe my background a little before describing what I believe is a fundamental problem the party needs to face down. Recently I have been asked on numerous occasions “what happened in May?”. It’s a dumb-ass question from a bygone age. What, you expect me to encapsulate what happened in a couple of glib one-liners? Get with the programme, politics hasn’t been like that for years.

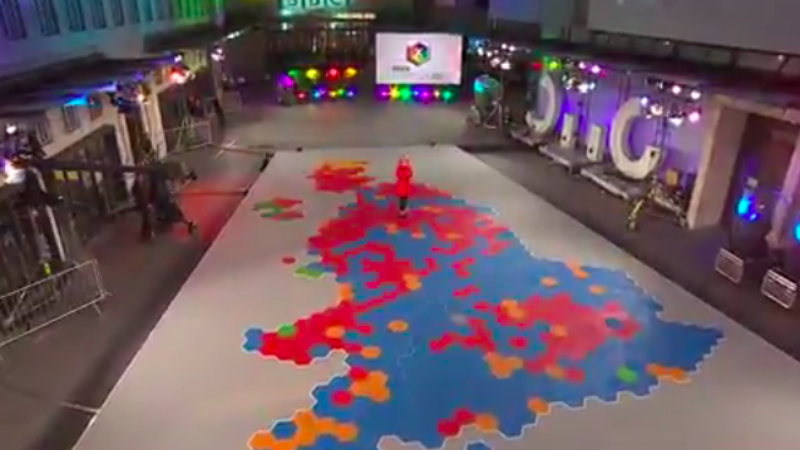

We have 650 individual elections every five years. Anyone who has followed my Twitter feed will have noticed I make that point a lot. The point I am making is that these are 650 unique contexts, with 650 incumbents, 650 sets of candidates, 650 political histories, 650 demographic contexts, 650 different sets of local stories.

Trying to encapsulate the complexity of our elections in a few bullet points is an idiotic way of describing what happened. Unfortunately there are plenty at it. I reject the exercise itself. I reject the underlying assumptions it places on the analysis I might carry out. I reject the view that complexity can or should be explained away under a few convenient headings. Instead I start in each constituency and seek to explain what happened there. It’s an approach I have taken, I’m happy to disagree with others about it, but I might be asked about them a year before the next election!

The way you conceive of politics must change. It is no longer practicable to believe that what happened nationally is either quantifiable or applicable in equal measure in each constituency. In fact, even trying to do so fails to inform a response which can be applied in the future. Imagine the numerous reviews which the party is undertaking come up with broad explanations for what went wrong in May. The first question any review should answer is “How will it win constituency x in 2020?” If the review doesn’t a) describe what went wrong in constituency x, and b) lay out how that can be changed between 2015 and 2020 then it’s useless. Literally useless – i.e. it can’t be used.

Which brings me to Arnie’s piece in LabourList. Arnie makes four recommendations:

1. “More meetings between national, regional and the organisers in the field.” Laudable, couldn’t hurt but too little. How about destroying central administration except for a skeleton staff and becoming a truly devolved institution? One of my frustrations is that Labour talks and sometimes acts a good game re: devolution but has failed to devolve itself! It can prove its capacity in this regard now. It doesn’t need to wait to be elected.

2. “End the dichotomy between the national leadership and staff in the field.” Again, laudable but Arnie doesn’t make any concrete suggestions as to how to do so other than the other recommendations so I’m not sure it should even be a recommendation.

3. “Free up organiser time to spend building relationships with communities.” Amen to that with bells on. Of course many local councillors do a fantastic job in this regard. An addition to this may be to ensure that councillors and MPs work together much more closely. Too often I have seen them, erm, not. Being fit-for-purpose at the local level is paramount.

4. “Training sessions to build capacity.” Again, agreed 100%, and we might add that it depends on who is delivering the training and how. There is also a significant need for better recruitment and training of new and existing members with regard to canvassing on doorsteps and community organising. Arnie would be well placed to help with this of course.

My own views on the party are predicated on the belief that the organisation must fit the environment in which it works. A mechanistic top-down super-state is no longer fit for purpose.

If you’re trying to win an election with a mechanistic and centralized organisational structure your machine is going to need three conditions to work well:

1. A straightforward task to perform.

2. A stable environment in which to operate.

3. Compliant human beings which behave as they are instructed.

I don’t think anyone in any political campaign would believe those conditions exist.

“A straightforward task to perform?” Running any campaign is anything but a straightforward task. Just ask Nigel Farage’s campaign team how easy it was to organise a humble town hall meeting. Or ask a comms team how easy it is to design a leaflet. Or tell a candidate which streets to work. Or issue a seemingly simple press release. Or effect a media strategy in the East Midlands. Or… well, you get the point. The complexity of any election campaign is quite enormous. Expecting any central machine to be able to handle such complexity is to place undue faith in its design.

“A stable environment?” I am firmly of the belief that the current political landscape in the UK is the most volatile it has ever been. Two-party or three-party politics is dead. Turnout is down, traditional alignments are looser than ever, more seats are changing hands than ever before, party loyalties are less and less important, party membership is still low and these factors show little sign of returning to their previous more stable and reliable levels. No matter how well a central machine is designed it is unrealistic to expect it to be able to ride this volatility. Au contraire, it may foolishly attempt to model it out. Wiser in my opinion to come to peace with it and adapt.

“Compliant human beings which behave as instructed?” Do I even need to expand on this? Why would we expect candidates, activists or MPs to obediently comply with diktat from on high when it is their necks on the line? I know of at least a dozen examples from all political parties where candidates on the ground either openly defied their own party or worked to rule. This shouldn’t surprise anybody. Many candidates put their lives on hold, sacrifice crucial family time and often underwrite their ambitions with the deeds of their house. I certainly wouldn’t be obediently towing the line if I were in their position.

Both the main political parties use this machine approach to campaigns. These approaches have severe limitations. They have great difficulty adapting to changed circumstances for a start. All too often they encourage an unquestioning machine mindset which encourages its employees to slavishly fall into line. The interests of those working in the organisation take precedence over its goals.

Which brings me to the central rub of this piece. Political commentators and bloggers like me need to recognise an all too human reason why decommissioning machine politics is tricky. The human beings within the machine are entitled to ask what happens to them if the machine is decommissioned. I certainly don’t underestimate this perfectly normal human instinct. “I’m happy to devolve power so long as I keep my job”, is completely normal.

So what to do? Firstly decommissioning any machine is a phased process. It doesn’t happen overnight, nor should it. Whatever mechanism is intended to replace the machine needs to be designed, trialled, tested, rebuilt, retested and then evaluated. Only then would the organisation be in a place to roll out the necessary reforms and begin the decommissioning. Such a process should take in at least one May election cycle and a representative sample of sites.

Second, there are certain to be parts of the machine which will be retained at the centre. Efficiencies of scale mean there are good reasons to do so. However where possible the intention should be to devolve power, authority and control as close as possible to the context in which it is to be effected.

Third, once the process of decommissioning begins it must be kept under continuous review to ensure the goals are being adhered to, and that its delivery is not being owned by those with a vested interest in retaining their own stake. This last point will require strong leadership, and I don’t presume it will be easy at all.

I’ve said enough. Fundamentally I believe that the political landscape has changed in ways which mean that Labour must adapt or be evolved out of existence. These adaptations will be difficult. There will be casualties but if the party is smart it can get ahead of these problems or it will be even less well placed in 2020.

More from LabourList

‘Labour won’t stop the far right by changing leaders — only by proving what the left can deliver’

‘Cutting Welsh university funding would be economic vandalism, not reform’

Sadiq Khan signals he will stand for a fourth term as London Mayor