The Fabian Society’s democratic reform programme covers, as it should, a wide range of useful reforms that need to take place to refresh – and maybe even to retain – a democratic society and a political system that reflects those values. I am proud to be part of the process and I will commend the whole programme for consideration when it is published (although I would go further on some issues like compulsory voting). But today I shall write about electoral reform.

As the Fabian programme demonstrates, voting reform is not a panacea for all the ills of the system but I would argue an indispensable part of the package. In this post I shall introduce some new research I have been working on about the specific damage the first-past-the-post (FPTP) electoral system does to Labour and progressive politics, and discuss the principles underlying the forthcoming Fabian Society democratic reform charter.

Social and demographic trends seem to be producing a new, biased, divisive political geography in many societies including Britain. Cities are becoming more cosmopolitan, youthful, economically successful and liberal. Parties of the left, centre left and green persuasion stack up huge margins of victory in urban areas while the hinterlands have seen once-solid working class left votes fragment and the centre and far right make relative progress. The result is that progressive votes systematically count for less in single-member systems like FPTP and AV.

One measure of bias is the difference between the average district and the median district. In the US in 2012 the average congressional district gave Obama a lead of 4.6 percentage points while the median district voted by 1.3 percentage points for Romney. If the Presidential election had been decided on a single-member parliamentary basis, Romney would have won comfortably despite losing the popular vote by a significant margin – allowing for the District of Columbia Romney led in 247 districts and Obama in 189. Deliberate gerrymandering is part of the explanation in the US, but even in non-gerrymandered states like New York and Massachusetts the concentration of liberal votes in the big cities creates electoral distortion. Even in the two states with Democratic gerrymanders (Illinois and Maryland) the median district was either more Republican than the average, or only biased by less than a percentage point rather than the double-figure effects produced by Republican gerrymandering in North Carolina and Michigan.

In the Australian election of 2016, the Liberal-National Coalition won a narrow majority of one overall and probably 76-69 (one seat is undetermined) over Australian Labor, with a lead of 0.2 percentage points in the two-party preferred national vote. Labor, on an even swing, would need a lead of nearly 3 percentage points to gain a majority.

Bringing the analysis closer to home, the Labour vote in the 2015 election was startlingly maldistributed. The Conservatives won a majority with less than a 7 percentage-point lead over Labour. Labour would need a 1997-sized margin of victory in votes (13 points) to scrape over the line with a majority of 1 on existing boundaries, and also assuming that the trend towards progressive votes concentrating in cities stops now, which seems unlikely anyway, let alone Labour’s recent political trajectory.

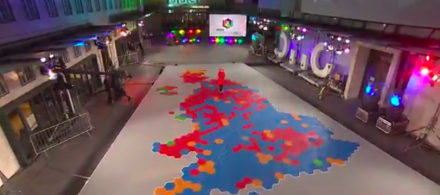

The EU referendum last month demonstrated the pattern once again. According to Chris Hanretty’s estimates Leave won the constituency count in England and Wales by around 421-152, a massive majority on a modest-sized lead in votes. The average constituency had a Leave lead of 7.8 per cent, while the median had a Leave lead of 11.4 per cent.

On the basis of this evidence, the liberal/ progressive side of politics has an inbuilt disadvantage of about 3-6 percentage points compared to the conservative side in single member district systems in several countries including Britain, even with constituencies that have not been gerrymandered. Left of centre defenders of FPTP have to ask themselves whether a permanent handicap of this scale – enough to affect the result and therefore the ability to deliver the core parts of the progressive agenda – is a price worth paying for the presumed advantages of single member constituencies.

This is not to say that the constituency link is not important; of course it is. Disadvantaged areas in particular benefit from having an accessible local representative who can hear their concerns and push their interests onto the policy agenda. Nobody is suggesting moving to a list-based PR system of the sort they have in Israel or South Africa.

There are several systems which combine a constituency link with a closer relationship between votes and seats at a national level. The single transferable vote (STV, as used in Ireland, most elections in Northern Ireland and in Scottish local government) does this by having several representatives per constituency (something that used to be the norm in Westminster elections, historically). The electoral system used for Scottish, Welsh and London government has single member constituencies but also regional “top up” representatives to bring the overall results closer to the shares of votes cast. Other transferable and top-up systems exist, for instance using the pools of “wasted” votes to choose additional members, a system its author Aharon Nathan calls “Total Representation”.

One of the depressing features of the electoral reform landscape is that many advocates are so wedded to one particular system, while the Fabians’ democratic reform initiative starts with the principles – a constituency link and a reasonable degree of proportionality.

For advocates of proportionality, compromising with the need to have a local representative and a parliament that one can form a workable government with – rather than a gaggle of factional purist parties – is reasonable. For someone who values a constituency link, it is a fair compromise to accept some compensating mechanism to ensure that our elected bodies are more representative of the votes actually cast and that fewer people have nothing to show for their trip to the polling station other than an unfashionable sense of civic responsibility. For the left in particular, is it better that a plural left gets more or less its fair share of seats than smaller parties getting crushed by the system while the largest party needs a landslide margin in votes to actually govern? In the long term, can we afford as a society to permanently disempower young people, the urban centres of growth and our minority communities?

More from LabourList

‘A third way approach is needed to protect children online’

‘Lammy’s jury trial cuts risk worsening racial bias in justice system’

‘Is there an ancient right to jury trial?’