In confronting the two great foreign policy challenges facing the UK, Labour needs to draw inspiration from the great Labour prime ministers of the past, and adopt a classically social democratic approach which will reassure our core supporters that we are guided by the history, experience and fundamental values of our movement.

First, Nato is threatened both internally by Donald Trump’s ambiguous and sometimes downright hostile attitude to the alliance, and externally by the resurgence of Putin’s Russia as a conventional military power, backed by a nuclear arsenal, seeking to project power and create a hegemonic regional role both in its Central and Eastern European “near abroad” (including non-Nato states like Ukraine and Nato members like Poland and the tiny and vulnerable Baltic States), and in the Middle East.

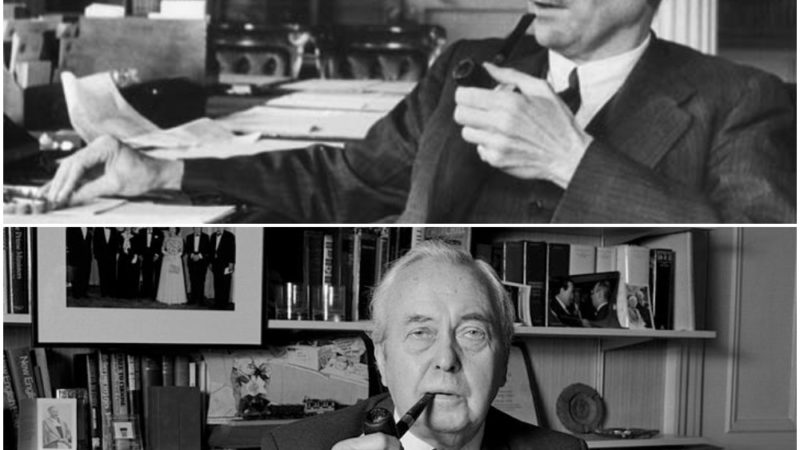

Labour needs to be clear that Clement Attlee and Ernie Bevin were as responsible for creating Nato and the British nuclear deterrent as Attlee and Bevan were for creating the NHS, and based on very similar values of solidarity. Nato exists to enshrine the fundamentally concept of solidarity in the field of defence. Member states are obligated to offer collective security so that an attack on one member is considered an attack on all members.

Thus the militarily strongest democratic states in Europe and North America are responsible for the security of the weakest ones, and they cannot be picked off in the way Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania were by the USSR in the era of the Nazi/Soviet pact at the start of World War Two. As the states that are being protected are all more democratic (even Turkey, the least democratic one) and have higher levels of internal social justice than the state potentially threatening them, Russia, this is a mechanism for preserving social democratic values from external military threats. It is a social democratic way of doing foreign and security policy to stand up for small democracies like the Baltic States against powerful, bullying undemocratic neighbours.

Labour needs to argue that Britain needs to use the leverage it has as a country Trump claims an affinity with to persuade the US to continue to be the ultimate guarantor of European security through Nato, but at the same time assuage Trump’s disgruntlement about the Europeans not pulling their weight and free-riding on US funded defence by leading by example both on the obligation to spend a minimum of 2 per cent of GDP on defence (which has the benefit of Keynesian pump priming of our economy, particularly in highly skilled jobs and particularly in regions that really need them) and on preparedness to deploy British ships, aircraft and troops to help deter Russian conventional threats in the Baltic region.

We should argue against the double counting of some international development spending as contributing to defence targets. It does, but it won’t help deter a Russian tank division from rolling towards Tallinn or Riga, so we should call for the government to meet its 2 per cent Nato spending target and its 0.7 per cent international aid target, not count the same spending twice. Britain needs to take the political leadership within Nato’s European pillar too, building a commitment across all the European Nato states to strengthen their defence capabilities in case the USA ceased to be a reliable security guarantor.

With the doubts about the US’s commitment to the defence of its allies that Trump is creating, the good sense of Attlee in creating an independent British nuclear deterrent, and of more recent governments of both parties in renewing Trident so it will protect us for many decades to come, is even more self-evident. Attlee was informed by the horror for Britain of the 1940 fall of France, whose army Britain has relied upon to deal with the land threat from Germany. The moment of sudden need to be wholly responsible for our own defence in the summer of 1940 has shaped British security ever since – you create the best mutual defence alliances you possibly can with the most powerful allies, but ultimately you need to be independently able to deter aggression by your biggest threat if those allies for any reason abandon you.

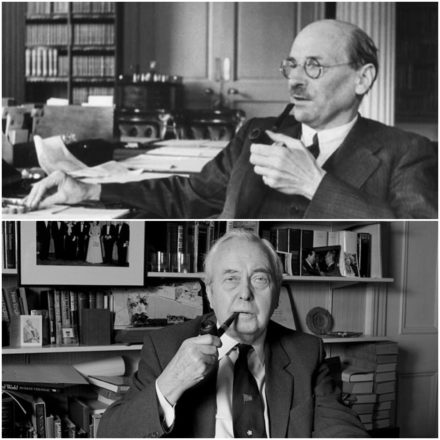

Second, Brexit. On this we need to look at how the ultimate pragmatic party manager as PM, Harold Wilson, handled the European issue. Then there were passionate pro-Europeans within Labour like Jenkins, and passionate opponents like Foot. It wasn’t nearly a left/right division – arch-modernising leader Gaitskell had been anti-common market. The division now is more between passionately wanting to fight on among pro-EU MPs and party members and voters in big cities especially London, and pragmatic acceptance of the Leave vote among MPs representing seats in the Midlands and North where many Labour voters voted Leave because of concerns about the economic impact of EU freedom of movement.

Wilson himself was probably quite sceptical about joining the common market but he wanted to avoid the party ripping itself apart on this issue. Then as now there was also a cross-cutting left vs right conflict in the party, and that was and is quite enough to deal with without creating a second split. For Wilson the referendum was a way to throw the European issue to a higher jury, the public, who would take the decision between the two arguments rather than it being fought out again within the PLP or at annual conference. The Tories foisted the 2016 referendum on the country for the same reason – to play out an internal split externally rather than split the party.

It would be ironic if the Tories now having united somewhat post-referendum, Labour which was fairly united for remain, even if our voters were not, splits after the decision on how to implement Brexit. We should apply the social democratic principle that one cannot ignore the will of the people. This was to leave the EU and anyone with any contact with voters will know the primary motive was to end freedom of movement and an implicit corollary of that is that the UK can’t stay in the single market as freedom of movement is one of its four principles. If we want to argue that a second referendum is necessary on the terms of Brexit that is a democratic argument to make, but it’s an argument better made by people who wanted a softer Brexit than by us remainers, and to win any second referendum it is actually better that the public are given a real choice – hard Brexit – than a fudge like Norwegian style EEA membership, which might make economic sense but politically would be the worst of all worlds – having to abide by EU rules including freedom of movement but with no MEPs or Council of Ministers seats to be involved in setting them.

Meanwhile, Labour should accept there is a government with a policy that means hard Brexit is likely to happen and draw up a social democratic vision for how Britain should develop as a nation after that. Theresa May outlined a dystopian fantasy of Britain being like a giant Singapore, a free market tax haven competing with the EU on the basis of lower workers’ and social rights and lower taxes and regulation. Labour should do the opposite, look at what the market-friendly aspects of the EU have prevented the British centre-left from considering and outline a society that rather than relying on the EU’s minimum levels of social and workplace protection, comfortably exceeds them. We should design policies that would give us better rights for workers than exist in the EU; trade policies that better protect workers; a big programme of state aid – banned by EU competition rules – to strengthen and attract overseas investment in our best industries like automotive and aerospace and invest in emerging and green technologies; a trade deal with the USA that has none of the EU/US TTIP deals issues, including threats to the NHS; procurement policies across the public sector that favour UK based suppliers – banned by the EU – and ensure every pound of taxpayers’ money creates and sustains jobs as well as buying equipment and services.

Sadly – I have been a pro-European all my life – as a democrat I have to accept the verdict of the referendum is that for now we are leaving the EU completely, and not even for some half way house. The time for anger and passion about whether we are in the EU was in May and June last year on the doorstep, not now shouting at the telly or on social media. But as a social democrat I think Labour has a duty to develop and propose a vision for a social democratic Britain outside the EU. After all, the great achievements of our governments in the 1940s and 1960s, and of the Nordic social democracies and Austria over many decades, were all achieved outside it. It’s not compulsory to be in a supranational body to achieve social justice in your country. We are going to have to see if we can deliver it here in Britain.

More from LabourList

Almost half of Labour members oppose plans to restrict jury trials, poll finds

‘How Labour can finally fix Britain’s 5G problem’

‘The University of the Air – celebrating 60 years of Harold Wilson and Jennie Lee’s vision’