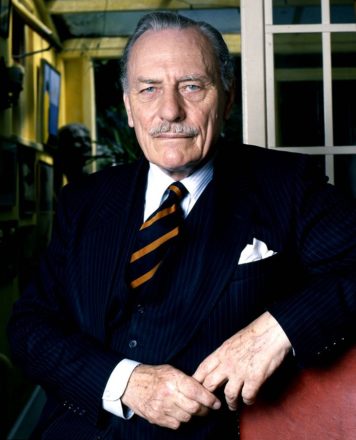

The controversy surrounding the decision to air Enoch Powell’s Rivers of Blood speech has reminded us how, 50 years on, it still has the power to shock and offend. But the hatred that courses through each line, offensive distortions and carefully crafted phrases designed to whip up fear and hostility are much less shocking than how depressingly familiar the echoes of Powell and his arguments are in our mainstream political debate.

A decade before that speech, my dad arrived in Britain from Calcutta to find colour bars in operation, denying him and thousands of others work, housing and entry to pubs and social clubs across the country. That oppressive reality created a generation of civil rights leaders and activists who together built the institutions, laws and partnerships that changed Britain and brought hope flickering back to life.

His contribution – founding the Runnymede Trust, co-authoring the Race Relations Act and establishing the Equal Opportunities Commission – was one part in a wider movement of campaigners, trade unionists and Liberal, Labour and Conservative politicians that gave many in my generation a sense that the arc of history inevitably bends towards progress. The last few years have been a stark reminder that it doesn’t.

Attitudes towards immigration may have become much more positive in the last decade, but concern about the impact of immigration on cultural life in Britain endures. Polling for Hope Not Hate this week found four in 10 of us think our multicultural society isn’t working, while nearly as many see Islam as a threat to the ‘British way of life’.

With Islamophobia and anti-Semitism on the rise, political leadership is badly needed. As Manchester University’s Rob Ford puts it, we are deeply divided in our attitudes to immigration “by age, education, class, heritage and economic insecurity. Almost all of those divides are growing.” Those hardening, polarised attitudes are why wrongheaded attempts to find the middle ground, or split the difference, will always fail.

Extremists find fertile ground in insecurity. As Jonathan Freedland writes, decent incomes, housing and opportunity are essential “to starve them of the oxygen that allows them to thrive”. But behind this pervasive anxiety is also a deeper sense of loss and a belief that we have staked out a future hostile to the things that matter most: time with families, dignified, meaningful work and the shared spaces and community institutions that embody our history, mould our identity and – as Jesse Norman once wrote – “help to shape and define us as we shape and define them”. ‘Take back control’ resonated in areas where their loss is palpable. In a world spinning out of control, change is frightening.

The remedy to this is power. I’ve seen it in my own constituency when Serco placed hundreds of young asylum seekers into a hotel in a small village without warning. It caused chaos until people were empowered with knowledge and the ability to act and responded with warmth and generosity. Compassion, tolerance and understanding do not endure in a climate of fear but they thrive in a confident, empowered society.

But what is the glue that holds this society together? Powell’s revolting invocation of the River Tiber foaming with blood drew up a nightmarish vision for Britain. That was his vision, but where is ours?

A long familiar campaign, from Rivers of Blood to the shameful Breaking Point poster, has sought not only to persuade us that migrants are to blame for our problems, but to airbrush their contribution from history and in doing so to airbrush ours. The city I grew up in, Manchester, was shaped by waves of immigration, while in Wigan and across Lancashire the two sides of my heritage came together when textile workers stood shoulder to shoulder with Indian cotton pickers at huge personal cost.

This history of graft, friendship and strength, often against the odds, of millions of working people and migrants who fought for economic and social progress and against racism and “do so still” as the playwright David Edgar says “because it’s the right thing to do” is not the only story – but it is one that must not be forgotten. If we allow the story of Britain, and what makes us who we are, to be claimed by the right, we will never claim the future.

When I grew up in 1980s Manchester, as a child with mixed heritage, the anger of the Moss Side riots was still palpable and racism was an everyday feature of daily life. Yet despite the brutality of the police and the cruelty of the playground there was a sense of progress. Last year another of my generation, the American writer Ta-Nehisi Coates, wrote movingly about his decision to write about, and therefore be defined by, race. For my father’s generation it was not a choice. The gift they gave us was that our race need not solely define us. Who can now say that is true? The depressing familiarity of Powell’s speech today should be a warning to my generation that we must pick up the baton and hand this country on in a much better state to those who come next.

Lisa Nandy is MP for Wigan.

More from LabourList

‘A third way approach is needed to protect children online’

‘Lammy’s jury trial cuts risk worsening racial bias in justice system’

‘Is there an ancient right to jury trial?’