The huge disappointment across the higher education sector following the Migration Advisory Committee’s no change policy on overseas students visas is further testament to the sector’s frustration and the threat to our world class educational impact. As crunch time on Brexit creeps nearer, this government is taking its eye further off that ball.

HE groups, universities and our internationally renowned research institutes – the Royal Academy of Science and the British Academy among them – along with myself and Labour colleagues have been sounding the alarm ever since the referendum about the potential decline in the UK’s share of the market in attracting students and researchers. Our role as a world-class brand and a continuing link between Europe and the rest of the international HE market and institutions is in jeopardy and the government is failing to put in place a strategy to combat it.

When Theresa May’s new government introduced their Higher Education and Research Bill, we pointed out all through its parliamentary scrutiny that it was deficient in addressing the new challenges that the Brexit referendum result would open up. Since then we have continued to press ministers as to the vacuum in their policies beyond 2020. Successive ministers have put off the searching questions coming from all sectors of HE about its impact on them. The recent release of the ‘no-deal Brexit’ papers showed how the government is so mired in the nightmare on Brexit Street that their global Britain is merely a slogan not a strategy.

They said belatedly, after much outside pressure, they would underwrite existing EU funding until 2020 – but there’s little clarity as to how we could continue participating in Erasmus+ post 2020, so crucial for both our and EU students who contribute to our economy in and our HE institutions and universities. The European Social Fund and structural funding that has so boosted many of our community base universities will go – and all we have so far is the vague promise from government of a ‘domestic prosperity fund’ to replace it. No funding price tag or details have been forthcoming. Meanwhile government strategies for preserving our international research networks – often mediated via the EU – hang in limbo.

ESF funding is a crucial primer for maintaining HE programmes at many FE colleges and modern universities, which are a crucial element in their survival. If the LEPs who take that collaboration process forward lose that funding, the programmes at sub-regional level and hundreds of thousands of jobs and skills are at risk.

Ministers desperately try to mouth mantras about new global opportunities to strike new deals across the world post-Brexit. But in practice, higher education, one of our strongest exports, is being given few bullets to fire by government. Indeed they risk shooting our universities and colleges in the foot.

Their treatment of Indian students is a classic example. India should be a huge market for the UK in the educational sector, given our historic, linguistic, cultural and social links. Yet when the UK immigration regime was overhauled recently, nothing was done to strengthen it. India was not on the list of countries from which students would have the ability to apply with reduced documentation for tier 4 visas, a sore point with the Indian government. There is little point Theresa May going to India on trade missions if Indian students vote with their feet and desert the UK for other more welcoming destinations.

Theresa May’s recent whistle stop tour of Africa was similarly well behind the curve in comparison to our international HE competitors. There is little depth or focus to the government’s air miles offensive, which merely brought us a new song and dance routine from the PM.

And now it seems the HE minister is focussed on pursuing his predecessor’s obsession wotj nebulous, untested private sector and often narrowly-focussed HE try-outs instead of reinforcing jobs, earnings and initiatives in our existing non-for-profit HE institutions in the international market. This includes supporting key EU programmes such as Erasmus+, which last November the EU doubled the funding for and tripled the number of potential participants – and the successor to the Horizon 2020 research programme, which UK universities have benefitted hugely from. These will dominate the 2020s across Europe and also have an impact outside it.

If the Government are serious about our being a global Britain, they need to address these issues with the effort and detail they deserve now. Otherwise they will not be forgiven, either by the current crop of UK students and their successors or their families and friends, who have seen the life-changing opportunities such programmes bring. British business is looking on anxiously with the CBI warning the UK workforce requires more graduates with international awareness and foreign language skills.

The Horizon programme is subject to the same uncertainty: “without a withdrawal agreement, after 29 March 2019 the UK will only be able to participate in EU programmes as a third country. That means it has no automatic right of participation.”

This is very worrying. The Financial Times reported recently that the share of European funding allocated to British universities is already slipping. BEIS figures show that the proportion of funds allocated to UK universities dropped to 24.22% by the end of May, Universities UK say British researchers have lost out on €136m since February last year, compared to previous levels.

The government is overlooking the multi-layered threat of Brexit to our HE institutions. It is not just the funding and engagement with Europe we are missing out on, it is the avenues around the world that are open to us thanks to EU partners. UK universities and their business and third sector partners risk the EU becoming our rivals instead of being a valuable collaborative partner.

There’s a multitude of other post-Brexit questions government must get to grips with urgently. The status of international students – both from the EU and the wider world. – And what tuition fees will they have to pay? Will this government follow the example of other nations, such as Australia and New Zealand to strike a reciprocal student fee arrangement with the EU as suggested by Million+ and others? And what will the visa situation be for staff and students and for the latter what post-study work visas will be available to them following the MAC report?

The UK benefits hugely at present from the soft power and influence such student experiences give us subsequently. The UK has consistently been in the top three EU countries in terms of numbers for such exchanges. We underestimate them at our peril. So when will the government finally take international students out of net migration targets? Despite evidence across the spectrum of the positive benefit to the UK – and evidence that the overwhelming majority leave before their visa expires – the Prime Minister continues a policy that shows hostility and an unwelcoming attitude.

With the Migration Advisory Committee now admitting they “do not see any upside for the sector in leaving the EU”, Theresa May must at the very least give higher education the attention it deserves to mitigate the potential damage of Brexit. She should allow ministers to look again at migration rules, and also give international postgraduates some flexibility to contribute economically to the UK. That should be something we all need, wherever we are on the Brexit spectrum, to see done – and rapidly.

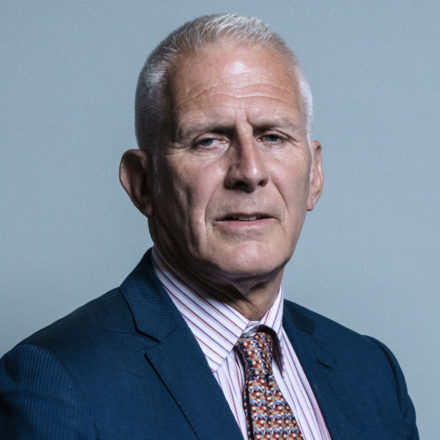

Gordon Marsden is MP for Blackpool South and shadow higher and further education minister.

More from LabourList

‘Labour’s quiet quest for democratic renewal’

‘Labour promised to make work pay. Now it must deliver for young people’

‘Council Tax shouldn’t punish those who have the least or those we owe the most’