The English Labour Network is going nationwide. We will ask how Labour can reach voters we struggled to win last time: those living in smaller towns, often working class, older, non-graduates, who see themselves as more English than British. The most recent event was in Stoke-on-Trent with Ruth Smeeth MP, Gareth Snell MP and the Labour candidate for Stoke South, Mark McDonald.

I was in Stoke for Gareth’s by-election in 2017. Too much Guardian reading led me to expect down-trodden, despairing, backward-looking people. But the voters I met were proud – proud of themselves and their families, proud to be from Stoke, proud to be part of this nation. They did want to believe in a better future, and many weren’t sure that any politicians, including us, really wanted to stand up for people like them. We won Gareth’s by-election but have lost in too many similar places in England.

Two years later, England is even more deeply divided: by age, by geography, by class, still – too much – by race, and by education. There is an underlying gulf in our values between a younger England, more liberal, more cosmopolitan, up for change, centred in the big cities, and an older England that feels change has made things better for others but not for them. It’s also about power. Real power lies with the elites, but the young and highly educated often feel more confident they can change the world than people who feel social and economic change has gone against them for the past 30 years.

Labour has been losing support amongst too many of those voters for a long time, even though they share our left-wing views on the NHS, redistribution and the welfare state. Many stopped voting for us in 2001. Working-class voters have swung away from Labour since 2005, and Brexit reflected the divisions but didn’t cause them.

We cannot build a stronger, fairer society on the foundations of a divided nation. Democratic socialism – ‘for the many not the few’ – needs a ‘many’ who identify with each other, and who want to work together to build a better world. The wreckage of Brexit, with England divided (as it would have been if Remain had won) into winners and losers, is corrosive for any progressive politics.

Labour support is getting weaker amongst people who are not well off, don’t think they are being listened to, and believe no one stands up for people like them. Who is Labour for, if not them? If we turn away, there are plenty of people ready to mobilise anger and powerlessness in dangerous directions. Many towns, like Stoke, have seen support for the BNP and UKIP rise, but as Ruth and Gareth argued, it is ridiculous to think these places are full of bad people. It is simply a manifestation of what can happen when people feel powerless and ignored.

Labour must win across this divided nation. There too few Canterburys and Kensingtons, and too many constituencies like my old seat, Southampton Itchen that, having list its traditional industries, is now Tory. The English Labour Network was the first Labour organisation to show that the next election would be decided in the England of the towns, the seaside areas and the old industrial villages; places outside and often disconnected from the major cities. These are patriotic places where people are proud to be both British and English, but more likely to say they are English. We also said that England is the most centralised nation in Europe. People in the towns are denied the tools, the powers and resources they need to shape their communities and rebuild their economy.

When I joined the party in 1976, we never talked about national identity. A lot has changed now. The big industries, heavily unionised, with tight-knit communities, generated a class- and Labour-voting consciousness that is much weaker today. But people still want a sense of identity and of belonging and increasingly it’s the identity people, place and nation that matters. It’s happening across western Europe and it becomes most intense when people think ‘no one speaks for people like us’.

This attachment to people, place and nation is forged by economic and social change, not politicians. Too often, though, the left has failed to engage. The populist right has been allowed to define nation as inward-looking and xenophobic; ‘people like us’ as people who are white. Identity is important because, no matter how good our policies are, if we seem to be very different, if we don’t share people’s sense of identity, no one will believe we stand for people like them. They won’t even listen to our policies. Shared identity is an essential point of connection with people who feel things are going against them, feel powerless, and feel no one stands up for them.

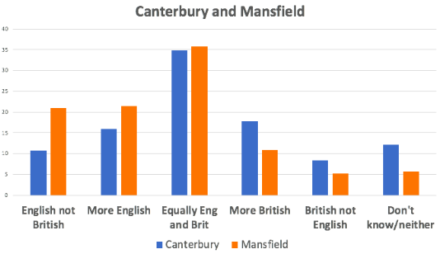

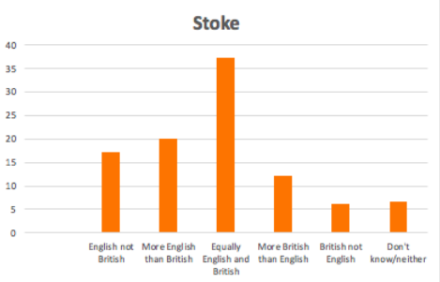

When we fail to talk about England, the message is clear: the connection is broken. And this is most critical in key towns. We won in Canterbury but lost in Mansfield, where there are significantly more English identifiers. Stoke, a former stronghold, where Labour held on to two seats but lost one, is another strongly English town. As everywhere else in England, Labour must speak to the British too, but it can’t talk only to Britain. Nearly 70% of the people of Stoke say they are proud to be English and three out of four don’t think they influence local decisions.

This is where we need to change. Labour doesn’t speak to England or the English, (as I’ve detailed before on LabourList) and our promises to shift power out of Whitehall are full of aspiration and lacking in any detail. In Stoke and many other places, potential Labour voters want to know we share their sense of local and national identity and that we are serious about giving them to power to reshape their communities and towns.

John Denham is director of the English Labour Network and a former Labour minister.

The next ELN event is in Hull on 17th November.

More from LabourList

‘I was wrong on the doorstep in Gorton and Denton. I, and all of us, need to listen properly’

‘Why solidarity with Ukraine still matters’

‘Ukraine is Europe’s frontier – and Labour must stay resolute in its defence’