Labour’s leadership candidates have found it easy to agree about immigration during this leadership contest. That reflects the broad pro-migration consensus across the Labour Party: it is at least one issue on which so-called Corbynites, Blairites and many of those in between, tend to see the world similarly. And it is not surprising that candidates during the 2020 leadership contest have prioritised the party audience – that’s where the votes are found. Yet the challenge beyond this contest, for all strands of Labour opinion, is how to make that case in a way that finds common ground not just within the party, but with enough of the public too.

The policy consensus of the leadership contest will be overtaken by events. The leadership candidates have all defended free movement after Brexit, as part of a future UK-EU relationship that stays as close to the single market as possible. Yet the Commons arithmetic shows how this argument was lost on general election night last December – so Labour will need to review this central element of its immigration policy again by the middle of the parliament.

In questions after his Brexit Day speech declaring that the Leave versus Remain divide must end that day, Keir Starmer proposed that Labour would restore free movement once the current government abolishes it. Those are difficult aims to reconcile: reintroducing free movement would be the single policy proposal most likely to split opinion down 2016 referendum lines. Any workable proposal to restore free movement would have to be located in a broader policy for the UK-EU relationship. Nobody could yet know where that may stand in four years’ time.

Labour’s current policy faces a tension between supporting the closest UK-EU links but also differentiating fairly between EU and non-EU migration. Labour’s main policy commitments on migration from outside the EU are driven by ethics, rather than economics. The new leader will face pressure to maintain commitments to end indefinite detention, let asylum seekers work and reduce the income thresholds for family migration. Much less thought has been given to how Labour would approach migration for work from outside the EU. The logic of current policy looks close to global free movement, for anybody with a job offer – but this may be more by accident than design.

Labour’s 2020 challenge in opposition is more about politics than policy – how it can rebuild what Lisa Nandy has called the “red bridge” to reunite Labour’s potential vote. The party’s internal conversation may be too narrow to do this. Often, when the Labour Party talks to itself about immigration, it is a conversation among people who don’t feel conflicted about immigration talking about how to secure the confidence of others who do. It risks becoming an exercise in trying to find the common ground with people who aren’t in the room. This can sometimes exaggerate or misread the views of the voters that Labour is trying to reach.

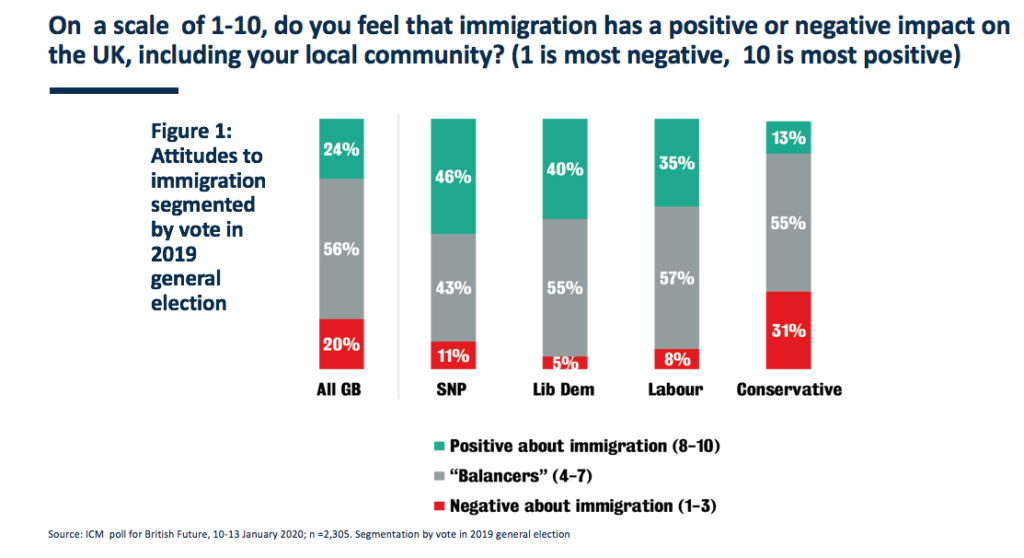

Labour isn’t likely to reach the voters with the toughest views on immigration: its challenge is to unite pro-migration liberals with left-leaning balancers, who see the pressures and gains of immigration. New attitudes research published today by British Future and the Policy Institute at King’s College London shows that most of Labour’s voters are in this ‘Balancer’ middle, alongside a significant share of strongly pro-migration voters.

It is possible to identify many approaches to immigration, integration and citizenship that could strengthen confidence across this broad coalition. Labour should speak up for an agenda that insists on fairness to those who come to Britain and to the communities that they join; which encourages and promotes citizenship; and which invests in strengthening contact and sustained solidarity across these groups.

Yet the speed and intensity of online debate can make this more difficult, artificially amplifying the polarisation of this debate. It has become common to observe that “culture war” politics can divide Labour’s electoral coalition. It is less often noticed that this can be bad news for the very social groups most likely to make up the left-liberal pro-migration tribe. Graduates, the under-40s, ethnic minorities and those who live in cities and university towns will find themselves stuck in a “coalition of the losers” unless Labour succeeds in broadening its appeal, electorally and geographically.

Without giving itself a chance of governing, it can’t do any of the things its core supporters might want. Yet this debate gets easily stuck if framed as a choice between the party’s core values and its pragmatic need for votes. Could Labour find more confidence in a bridging agenda if it thinks about this as a question not just of electability, but also of the mission and purpose of a centre-left party in polarised times? Those who seek to govern must then show that they can bridge the divides between the towns and the cities, between majorities and minorities in a shared society.

Our new research finds that voters in towns and cities have experienced the pressures and gains of migration differently, but they do not live on different planets. Labour’s next leader will need to show how responses to that bridging challenge can take practical form – if the party is to find common ground on immigration within the party, and also beyond it too.

More from LabourList

EXCLUSIVE: Usdaw General Secretary writes to PM ‘frustrated’ regarding changes to Employment Rights Act

Think tanks and MPs call for targeted response as Iran war impacts cost of living

‘This Labour Government needs to fix the Tory student loan fiasco’