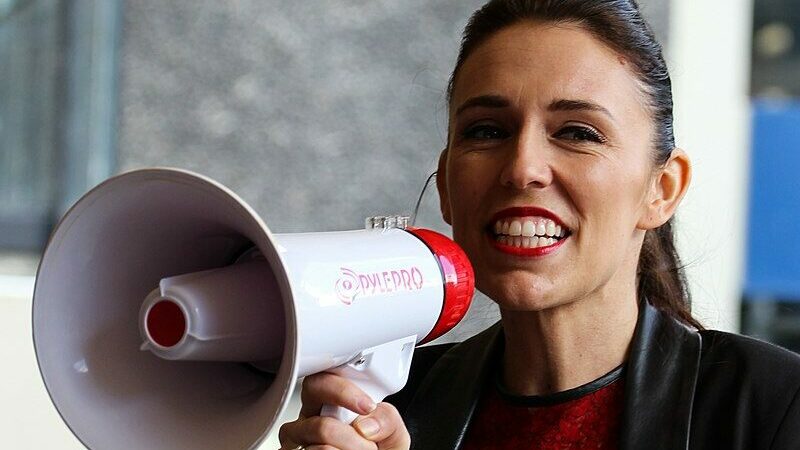

In the age of the Trumps, Johnsons and Bolsonaros, there has seldom been a bigger gulf in political and moral leadership at an international level. This vacuum has been hugely evident in the lack of global coordination and leadership in response to the coronavirus pandemic. Though there is little doubt that we are indeed living in the age of populists – trading in easy answers to complex questions – there remains a small group of leaders who continue to stand out. Merkel in Germany is, of course, the obvious example. But I’m sure if you were to take a straw poll and ask who has impressed most during the Covid-19 crisis, Jacinda Ardern would be the near the top of many people’s lists.

Ardern has won a number of plaudits from around the world in recent months for New Zealand’s handling of the pandemic, having now officially eradicated the disease – something that many argued was impossible. Doubters will be quick to point out that this was made easier due to the country’s smaller, more sparsely separated population. While there may be some truth in this, it fails to recognise that – at the peak of the virus – New Zealand had over 1,000 cases and the country still has a number of densely populated areas. Auckland alone, for example, is a city of 1.7 million people.

In reality, the real difference between New Zealand and the UK is decisive leadership. New Zealand acted fast and early to deal with the virus, going into lockdown almost immediately, to save lives. Here, we were told that going into lockdown too soon would cost jobs and damage the economy. New Zealand is now out of lockdown and has just ended social distancing, suffering only 22 deaths. The UK has the second-highest death rate in the world and is on course to suffer the worst economic damage of any developed country in the world. Leadership matters.

Ardern’s approach in dealing with coronavirus has been a lesson to the world in leadership, as was her response to the tragic Christchurch terrorist attack in 2019. But her domestic record is just as impressive, and there are lessons here too – particularly for UK Labour. Before Ardern become leader, the New Zealand Labour Party had been out of power for nine years, lacking credibility on key issues like the economy and immigration. In changing this, she has had to show flexibility – putting aside ideological purity in favour of pragmatism – while still managing to put forward a radical policy agenda.

Ardern is a social progressive first and foremost, but recognises the importance of community and that many people have been left feeling uncomfortable with certain elements of globalisation and deep flaws in the neoliberal model. This is something that UK Labour failed to do when last in government. Ardern has highlighted how unchecked capitalism has seen rises in homelessness and had a profound impact on the environment. She has also favoured stronger controls on migration, focusing on skilled immigration, and recognised that increases in the number of people coming to New Zealand has put considerable pressure on public services. Crucially though, rather than simply blaming immigrants and immigration, her government has invested in housing, infrastructure, public services and provided training for New Zealanders – so that local people can help fill skill gaps in the economy rather than relying on labour from abroad.

Last year, New Zealand became the first country in the world to drop GDP as the sole measure of national progress. The government instead focused on people’s overall wellbeing and put forward a ‘wellbeing budget’, which included millions to tackle poverty, family violence and improve mental health, as well as a number of other measures to improve people’s quality of life. Crucially, this recognised several things. Firstly, that too many New Zealanders felt left behind by globalisation, not feeling the benefits of change. It acknowledged that people don’t measure their own lives in terms of GDP, so why should governments? And, most importantly, it reaffirmed Ardern’s commitment to tackling poverty and making material improvements in people’s lives. The first duty of government.

Remarkably, Ardern has managed to put forward a radical policy agenda while addressing her party’s traditional lack of credibility on the economy, via commitment to a set of budget responsibility rules, setting critical limits on public debt. All governments and parties around the world should look to Ardern and New Zealand as an example. But Keir Starmer’s Labour in particular should pay special attention.

At this point, we have no idea what the post-coronavirus world will look like. But if Labour in the UK is to have any chance of winning power in 2024, the party must tackle some of its past failings in the same way Ardern’s has. This means putting forward a radical policy agenda fit for the 21st century, recognising the things that drive people – community, quality of life and wellbeing – while regaining credibility and trust on immigration and the economy. It’s a tall order, but as Ardern and New Zealand Labour have shown, it is possible.

More from LabourList

‘Turning public services around: Haringey’s story of child protection’

‘Can Labour turn the green tide back to red?’

Tom Belger column: ‘Why is Labour making migrant exploitation easier?’