In the aftermath of Labour’s 2019 general election defeat, there were two explanations ready to go. The first, favoured by the party’s right-wing, said we were ‘too left’. The second, endorsed by sections of its left, was that we were ‘too Remain’. I argued at the time that these were closer to propaganda than analysis. They were better placed to reassure party members and lay the ground for the coming leadership contest than they were to explain the defeat.

Not much has changed since. Despite excellent analysis from Labour Together and others into the defeat, these remain the dominant accounts. The Brexit argument has evolved further into a narrative of betrayal. Remain-supporting left-wingers, the story goes, collaborated with Corbynsceptics to throw the election and remove the left from the party’s leadership. The problem is not just that it’s untrue, but that the myth serves as a major obstacle on the left’s route to power.

Does Brexit explain Labour’s 2019 defeat?

Last December, Labour suffered its worst defeat since 1935, in an election that was defined by Brexit. Any analysis of the outcome must consider the role of the referendum. But the ‘betrayal myth’ goes further. It does not just identify Brexit as a key factor – it suggests that saboteurs pushed the party from a Brexit position that would have won the election to one that was bound to lose. It does not add up.

What are the facts? We know that between 2017 and 2019 Labour lost more Remain voters than Leave voters, but while Remainers were concentrated in strong Labour constituencies, marginal seats were disproportionately in favour of Leave. The result was that all but two of the English seats lost between the two elections had voted Leave.

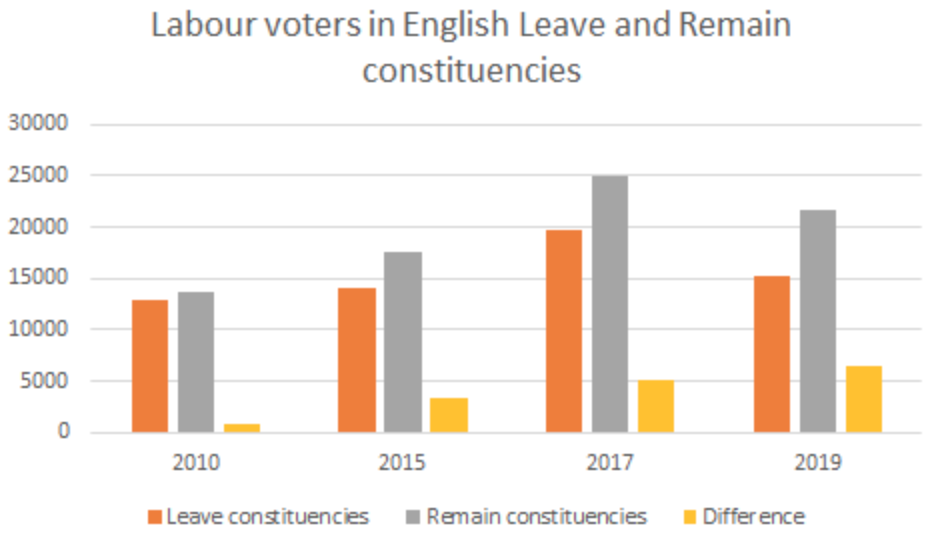

Why did we lose these Leave voters? The question suggests an obvious answer: they wanted to leave. But this cannot explain the long-term trends. Over the past decade, Labour’s support in England has become increasingly concentrated in Remain areas. This process was underway well before the referendum even took place. In 2010, there were already on average 800 more Labour voters in English Remain constituencies than Leave seats and this figure has risen steadily – 3,500 more in 2015, 5,200 more in 2017, 6,400 more in 2019. If the trend began before the referendum was even called, then it cannot, by definition, have been caused by the referendum itself.

The truth is that Remainers and Leavers differ in many respects, not just their view on the European Union. On most issues, Remainers are more closely aligned to Labour’s values and policies. They are more likely to oppose US foreign policy, to accept as British the children of immigrants and to support the movement for women’s rights. Leave voters are more likely to hold reactionary views on asylum seekers, believe torture is acceptable in some circumstances and think benefit payments are too high. On a whole range of issues totally unrelated to Brexit, Leave voters were bound to find themselves disagreeing with Jeremy Corbyn. This is more about deindustrialisation, homeownership and age than it is about Europe.

Was Labour’s Brexit position a betrayal of the left?

A different Brexit position would not have won the 2019 election. A pledge to leave the EU would have undoubtedly held onto some Leave voters, but it is unclear how many. It would have probably slowed down the decade-long ‘Remainification’ of Labour’s vote, but it would have neither halted nor reversed it. We also don’t know how many Remain voters the party would have lost in such a scenario, and whether this would have cost Labour seats elsewhere. Leaked internal polling suggests that had the party not promised a second referendum it would have 124 seats – more than double the 60 we lost in reality. Of course, we will never be able to know for certain.

Regardless of whether a different Brexit position would have cost us seats or allowed us to hold onto a few more, it looks highly unlikely that any position would have led to an election victory. We would have still lost, just in a different way. My concern with the betrayal narrative is not just its poor analysis, but that I think it is self-defeating for the left. It undermines the Labour left’s own arguments on electioneering and party democracy.

The left has always rejected triangulating to appease swing voters. When the party shifted to the right under Tony Blair, it did so to reach ‘middle England’. The party’s left argued, correctly, that chasing swing voters may be effective in the short term but if the party ignores the needs of its core supporters, they will eventually become alienated and defect to other parties, such as the SNP or UKIP, or even disengage entirely. In 2015, a key promise of Corbynism was to take the party back to its roots and deliver for its base. The Brexit betrayal myth, by contrast, suggests that the party’s position on the defining issue of the day should cater to the minority of its voters who wanted to leave the EU just because they live in marginal constituencies. Once you accept that, you cede ground on every other issue.

The betrayal myth also undermines party democracy. The Labour left has always argued for a member-led policy process. It is hard to overstate how much Labour members wanted to Remain. As Corbyn recently recalled: “The party could have just reiterated the 2017 policy… But the strength of support in the party was absolutely huge – as was reflected in the pressures of the 2018 conference.” Polling of party members at the time confirms his analysis.

At the 2018 Labour conference, over 100 constituency parties submitted motions calling for a second referendum, more than for any previous topic in the party’s history. The motion passed overwhelmingly. Even after the election defeat, 64% of party members still felt that the party’s position on Brexit was either correct or insufficiently pro-Remain. It is simply not possible to argue for Labour to have adopted a pro-Leave position without fatally undermining the case for party democracy. But that is precisely what the betrayal myth does.

Where next for the left?

It does not always feel like it, but the Labour left is in a significantly stronger position than it was six years ago. Thanks to the Corbyn project, we are much bigger. There are more of us, and we have new organisations and institutions through which we can continue to build the movement. Without Corbynism, we would not have Tribune, Momentum or The World Transformed.

But, ultimately, we are still not big enough. We were defeated in December because the public did not believe we could deliver on our promises. In hindsight, this is not that surprising. We had fewer than five years to persuade the population of the value of transformative socialism, with very little to start from. Although we were not successful, we have laid the groundwork. We have a lot more to build from now than we did in 2015.

The betrayal myth will hold us back. It teaches us to triangulate, even though this can never lead to transformative change. It tells members to be silent when we need their voice to shape Labour’s future. The majority of Labour’s members and voters wanted to stop Brexit. They tried to do just that by using the party’s internal democracy. They used the left’s preferred tactics to fight for a position held by the majority of the left. This is no betrayal of Corbynism – it is exactly what Corbynism promised.

More from LabourList

‘Council Tax shouldn’t punish those who have the least or those we owe the most’

Two-thirds of Labour members say government has made too many policy U-turns, poll reveals

‘Two states, one future: five steps on the path to peace for Israelis and Palestinians’