Britain may be an island, but it is not its own planet. Our economy, culture and political system are similar to others across Western Europe and we are subject to the same global forces. Yet mainstream political analysts rarely make even passing reference to comparable events on the continent. Commentators agree that the Labour Party is in serious decline, but their analysis of the 2021 election results suggests it’s a uniquely British phenomenon.

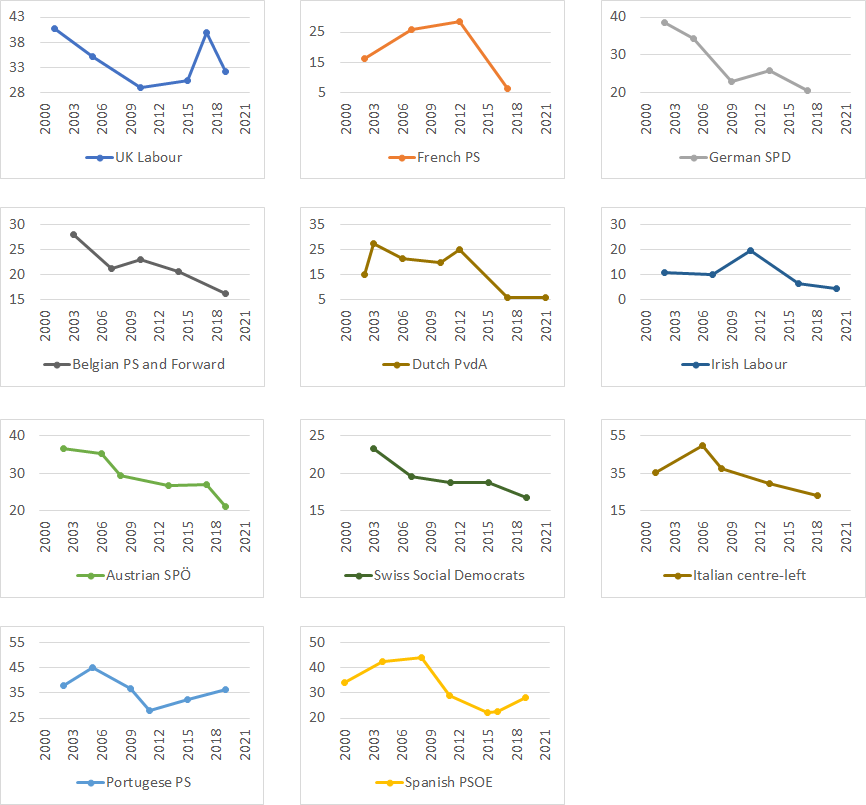

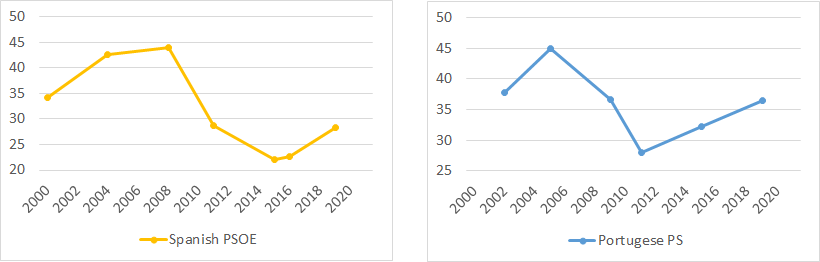

This could not be further from the truth. All of Labour’s sister parties in Western Europe have been losing votes since the turn of the millennium. There may have been peaks and troughs along the way, but not a single one polled better in its most recent major election than it did in its first of this century. This cannot be a coincidence. And if it is not, any explanation that relies solely on national factors is clearly insufficient. If we reduce Labour’s troubles to Brexit, Jeremy Corbyn or Keir Starmer, we cannot explain why the same problems exist elsewhere.

How should we make sense of these trends? For much of the 20th century, Labour and its sister parties won much of their support from the industrial working class. Thanks to deindustrialisation and the ageing population, this demographic is dwindling. Instead, each party is trying to hold together a coalition of increasingly disparate interests.

Take housing, for instance. A pensioner in a post-industrial northern town relies on the value of his house continuing to rise. He wants to leave an inheritance for the next generation and his home provides financial security if he ever needs expensive care. Meanwhile, the youngish worker in an urban centre faces sky-high rents and struggles to get on the housing ladder. She desperately wants house prices to drop. On this issue, their demands are contradictory, and yet Labour aspires to represent them both.

Housing is just one example. The gulf is widening between the older, small-town and younger, cosmopolitan sections of Labour’s voter base. They have different perspectives on patriotism, the police and multiculturalism. The former are anxious about change and keen to conserve the stability they have. Their politics are in the centre ground. The latter cannot see prospects for hope without transformational change so end up closer to the radical left. Unsurprisingly, this polarisation has accelerated since the financial crash of 2007. In the economic boom of the 1990s, centrism had wider appeal. After all, if life is relatively comfortable, why risk it with radical change?

A similar process has happened on the right wing of the political spectrum. Right-wing populists promote nostalgia for a non-existent past and exploit people’s fears about security or changes to our cultural fabric. As these forces on the extreme right have risen, traditional conservative parties have had to respond. Some have entered into a coalition with populist parties, like in Austria. In countries dominated by two ‘big-tent’ parties, the far right has won influence and power in the centre-right party itself, as with the emergence of the Tea Party and rise of Donald Trump’s nativism in the American Republican Party.

The centre left has generally had less success in responding to this polarisation. Only two of the graphs above show signs of recovery: Portugal and Spain. In both cases, our sister party is in government with the support of the radical left: the Spanish Socialists in coalition with Podemos, and the Portuguese Socialists with support from the Left Block. Another example where a centre-left party has been successful is in the US, where Joe Biden has proactively worked with the socialist wing of the Democrats and treats Bernie Sanders as a valued ally.

The conclusion from these experiences is blindingly obvious. The centre left and the radical left need each other. Neither is big enough to win on its own. Labour must appeal to Corbynites and Starmerites, those who read Jess Phillips in The Independent and those who follow Zarah Sultana on Instagram. This is manifested clearly in polling data. Starmer is more popular than Corbyn in the general population but only a few points ahead amongst Labour voters. Our younger voters prefer Corbyn, with the youngest cohort preferring him by an almost two-to-one margin. The only rational response to this situation is to use Corbyn and the party’s radical wing as valuable electoral assets, who can reach voters that the party leadership cannot.

The most frustrating element to Labour’s current predicament is that, during his leadership pitch, Keir Starmer claimed to understand this. Since then, he’s done the precise opposite, actively sidelining the party’s left wing. The most prominent left-wing member of his shadow cabinet, Rebecca Long-Bailey, survived less than three months before getting the sack and he made no attempt to replace her with someone from the left.

Under his watch, the party machinery has suspended dozens of leading left-wing members, stripped left-wing candidates of their credentials and manipulated shortlists to shut out popular left-wing contenders. The treatment of his predecessor, Corbyn, is perhaps the biggest tactical error. By shunning him, the leadership seemed to suggest that his supporters are no longer welcome, whilst also signalling that the party’s detractors were right all along. If Corbyn’s as bad as they make out, why should anyone vote for the party that happily campaigned for him to be Prime Minister?

Nowhere is the impact of leadership’s hostility to the left more clearly visible than in Bristol West. In 2017 and 2019, Labour won the constituency with over 60% of the vote, making it one of the safest Labour seats in the country. In the past year, the party machinery has suspended the Constituency Labour Party, removed many of the left-wing council candidates and removed the most popular – and left-wing – metro mayor contender from the shortlist. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the electorate that voted overwhelmingly for Labour less than two years ago this week returned 16 Green councillors. Labour has lost overall control of the council. Meanwhile, where the party put forward a radical vision, left-wing candidates and a united front, we did much better: as in Wales, Salford and Preston.

A bird cannot fly with one wing. The evidence from abroad suggests the left needs both its wings too. Neither is big enough alone to appeal to the broad spectrum of voters we need, but together we might have a chance. Making this coalition work may not be easy but it’s the only choice we have. It falls to Starmer to make the first move.

More from LabourList

‘Is there an ancient right to jury trial?’

‘To tackle the housing crisis, the Treasury must rethink how it values social housing investment’

‘Labour action on extreme poverty can stop voters going Green’