Ten years ago, Blackpool council sold off its entire stock of 6,000 municipal deckchairs, claiming the holidaymakers who preferred to sit on its new “sculpted spaces and the Spanish Steps leading down to the sea” had shown that the resort had “gone all continental“.

But European beach furnishing fashions were probably not uppermost in the minds of voters who backed Brexit in 2016 by the biggest proportion anywhere in the North West.

Three years later, a poll identified Blackpool South as one of the ten constituencies across the UK most opposed to immigration, even though hardly any immigrants live there. Indeed, the new Conservative MP elected for the seat in 2019, Scott Benton, claimed his victory had been driven by working-class loathing for what he called “woke and metropolitan values”, before devoting much of his energy to raging about the need to stop asylum seekers arriving at the other end of country.

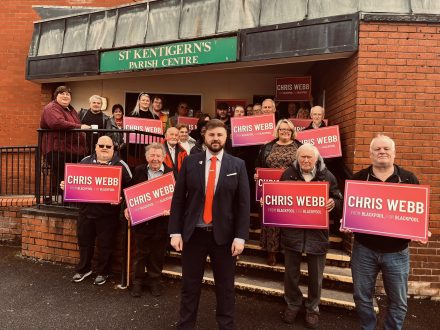

The abrupt end that Benton has instead brought to his scandal-clouded parliamentary career gives Labour a chance to win back the seat in a by-election today. And there’ll probably be lots of commentary over the next few days about Keir Starmer’s efforts to re-capture the ‘Red Wall’, whether Reform UK is enjoying a populist surge or if ‘levelling up’ has failed.

Since Brexit, the working class has often been treated as a job-lot

But the fate of those deckchairs may yet be a better guide to what’s been happening in politics over the past few years. In the new book I’ve written with Marc Stears, England: Seven Myths That Changed a Country – and How to Set Them Straight, we’ve got a long chapter on Blackpool and overwrought ideas of a traditional or, as it is often read, ‘white’ English working class.

This describes how the old wooden chairs were bought by a Cheshire-based business that has supplied lawn furniture for the stately home TV drama Downton Abbey. They were refurbished, preserving “the integrity of the original patina”, before being rented out or sold on as heritage items, either with their authentic worn plastic covers or with “new luxury fabric”.

The Stripes Company promised this would keep alive, if only in fancy gardens and corporate events far away from Blackpool, the “enduring image of postcard humour, knotted handkerchiefs, fish and chips and seaside landladies [that] are the stuff of legend”.

Much of the discussion about voters in northern towns in the years since Brexit has followed a similar pattern. Working-class people have been bundled up and retro-fitted to be used as ammunition for a culture war or, at least, to make them seem ‘the stuff of legend’.

Sometimes they’re labelled ‘left behinds’ or patronised as patriotic and under-loved ‘somewheres’ in contrast to those terrible elitist urban liberals who can live ‘anywhere’. On other occasions, they’ve been dismissed for being as backward-looking as the self-styled ‘fat bastard’ comedians that ply their trade in half-empty end-of-the-pier shows.

Only rarely in recent years have an increasingly diverse and divergent working class been recognised as anything other than a job-lot or an inert brick from that broken Red Wall.

Blackpool was never part of Labour’s ‘traditional heartlands’

It has coincided with Blackpool becoming a popular destination for politicians promising grand visions to restore faded glory or journalists seeking some human misery to flesh out a story about inevitable decline.

Certainly, there’s plenty of starry-eyed nostalgia in a seaside resort which used to be one of the most joyous places in the country, as well as the deprivation that comes from poor, sick or vulnerable people being washed in like so much flotsam on every socio-economic riptide. Government statistics published a few years ago showed that out of 33,000 council wards across England, eight out of the poorest ten were in Blackpool.

But this town was never part of Labour’s ‘traditional heartlands’, let alone a Red Wall. Campaigners for the party’s by-election candidate Chris Webb point out how, for three-quarters of its existence, Blackpool South has been held by the Conservatives. Gordon Marsden, who clung on as Labour MP for the remainder until 2019, says the town has always had a lot of “what might be called lower-middle class and working-class Tories”.

For that reason alone, no-one should expect Labour to win on the kind of swing it got in other recent by-elections. And nor should the town’s voters expect an instant transformation if a Labour government comes to power later this year.

Blackpool’s story is more complicated than politics usually allows

Like the story of the working class over recent years, that of Blackpool is a more complicated and muddled one than politics usually allows. It has a surplus not only of desperate need but also the rusting wrecks of grandiose and expensive solutions from a Las Vegas-style ‘super-casino’ and a Snow Dome that would ‘put the town in the big league’, to a tech hub called ‘Silicon Sands’. None of them came to anything.

Starmer, who has visited Blackpool several times in the past four years, is more likely to look for more prosaically everyday ideas like the crackdown on shoplifters he announced there on Tuesday in a speech at USDAW’s conference. He often describes a conversation with local six formers who obviously loved Blackpool. But when he asked how many thought they would have to leave if they wanted to fulfil their dreams, Starmer says that ‘they all put their hands up.’

That can’t be solved all at once. Chris Webb talks about working with local businesses and charities to build on the town’s resilience and tackle problems in health and social care or community engagement.

Lynn Williams, the Labour leader of the council, emphasises that everything depends on getting better funding for basic services but tries to get a fair share of levelling up cash. ‘When I hear a minister is coming,’ she says, ‘I fix my face, put a big smile on and say “thank you.”’

In the meantime, deck chairs are available for hire once more on Blackpool beach. They’re not council-owned and there are just a few hundred of them rather the thousands that existed before. A town with the word ‘progress’ in its crest was never meant to be a place that hankers after the past, but maybe a little dose of it now and again is no bad thing when there’s so much else to be done about the future.

Read our coverage of the 2024 local elections here.

If you have anything to share that we should be looking into or publishing about this or any other topic involving Labour, on record or strictly anonymously, contact us at [email protected].

Sign up to LabourList’s morning email for a briefing everything Labour, every weekday morning.

If you can help sustain our work too through a monthly donation, become one of our supporters here.

And if you or your organisation might be interested in partnering with us on sponsored events or content, email [email protected].

More from LabourList

‘Ukraine is Europe’s frontier – and Labour must stay resolute in its defence’

Vast majority of Labour members back defence spending boost and NATO membership – poll

‘Bold action, not piecemeal fixes, is the answer to Britain’s housing shortage’