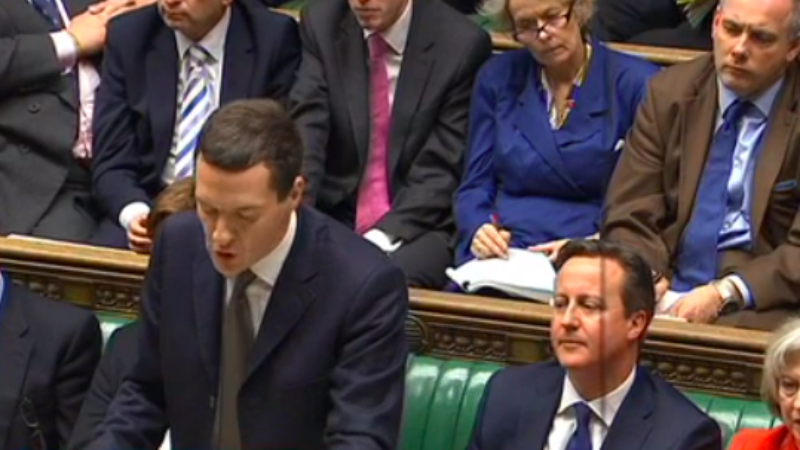

Labour has been hamstrung by George Osborne. The general election seems to be a choice between Tory cuts and Labour cuts. You wonder what the party would pay to have a single tactician as skillful as the Tory Chancellor. No budget without a headline catching gimmick that Labour struggle to meaningfully oppose. This week’s budget provided another blanket of comforting coverage for the Chancellor, just weeks before the general election. Yet, it also showed Labour that if it wins the election, it could do something quite remarkable. Labour could govern without making a single penny’s worth of cuts. This isn’t wishful thinking, or the road to financial market meltdown and IMF bailout. It’s very possible, and Gideon Osborne has accidentally given the game away.

Labour lept on the small print of the budget that showed quite clearly that the most brutal cuts are to come. Under Osborne’s plans £59 billion will be taken from total day to day departmental spending from £316 billion to just £257 billion. This isn’t adjusted for inflation – this is in cash terms. That £257 billion by 2019-20 would be eroded further still by inflation. Hence Labour’s effective jibe that the Chancellor wishes to take the state back to the size it was in the 1930s (in actual fact, it’s more like 1964). So how could Labour not make cuts?

The first thing to note is that Osborne has set himself a huge margin of error. He has allocated a further £20 billion worth of public spending for 2019 – 20 – which means, bizarrely, that public spending will fall – then rise by £12 billion in the last year of the next parliament. On top of this, in the last budget, he set a target for a huge (rather unprecedented) surplus of £23 billion by 2019-20. It is an understatement to say that surpluses are rare. Since 1955, there have been only three budgets where the Chancellor has delivered a budget surplus: 1969-70, 1987-88, 1999-2000 (Brown’s gigantic surplus was almost twice the highest post-war surplus as a share of national income). This super-surplus has now been revised down, once you factor in slightly faster than expected economic growth, it allows the Chancellor to deliver that last year of increasing public spending.

It doesn’t take an expert in economics to fathom that this final year of increased spending could, in fact, be spread across the next parliament to reduce the level of cuts required. Once you add in the commitment of both Labour and the Liberal Democrats to balance the books – excluding debt interest (eg a small deficit) – by 2019 – 20 (rather than including debt interest) suddenly cuts of £59 billion become cuts of £11 billion. This leaves a budget deficit of less than 2% of GDP and an economy growing at around 2.5% of GDP, leading to a fall in debt as a percentage of national income. Even at its peak next year, for all the talk of broken Britain, government debt will not rise much over 80% of national income. To place this into a historical perspective, government debt was over 100% of national income from 1750 – 1860 (debt didn’t stop the industrial revolution) and from the end of World War 1 to the early 1960s. These levels of debt are neither new, nor particularly high historically.

Labour may not wish to talk openly about tax rises, but a tax rise of £11 billion a year, around 0.6 of a percent of national output is a considerably smaller bill than the tax increases pushed through by Norman Lamont in the 1993 – 1994 budget (Lamont’s tax increases over 3 years were 2.67% of GDP – nearly 4 times higher than this modest proposal). It could easily be achieved. Freezing the personal allowance at £10,000 for the next parliament would simplify the tax code and also raise as much as £7 billion a year by the end of the parliament (if incomes rise 10% across 4 years – a low goal for any Chancellor). A one-off two pence increase on beer, petrol and diesel duties raises £1.1 billion. Increasing the tax business owners pay when they sell their business from a flat rate of 10% (yes, less than the lowest paid) to 15% (yes, still lower than the lowest paid) raises £500 million. Once you factor in Labour’s pre-existing tax pledge on the 50p top rate of tax and the mansion tax you have your £11 billion. Job done.

Suddenly, from Labour implementing cuts – Labour could tell the public it will tax them a little more (through freezing the tax free income tax threshold), but they get a clear offer: not a penny cut from the current budgets of important government services from the NHS to education, defence and policing. Of course, in real terms there will be a squeeze, but with inflation set to remain below one percent this year and potentially next year, the squeeze will be manageable in the short-term and could be achieved through efficiency savings. Giving government departments the safety their budget is fixed for 4 years will help innovation and reduce uncertainty. Moving budgets within departments – for instance rebalancing the local government budget to support Liverpool and Hackney (with cuts of £320 per person) by taking the money from leafy Epson (with cuts of only £15 per head) – would help rebalance the cuts and not require additional spending. Some sacred cows would have to be slain. The international development budget would be held – but would dip below 0.7% of GDP. The NHS would need to make serious savings as budget pressures mount. Defence would likely dip slightly below the UK’s NATO target of 2% of GDP. Yet, the economy would be bolstered. Labour could commit to closing the deficit and regain market confidence while keeping £32 billion a year in the economy. This stimulus could close the deficit still sooner.

The election can be recast from a choice of cuts. Labour can maintain spending levels while reducing the deficit, the alternative is Tory cuts that begin to look like an ideological choice not political necessity. Labour just needs to be honest on tax rises – and trust the public. That’s the challenge for the two Eds. Do they have the bottle to trust the people?

More from LabourList

‘Help shape the next stage of Labour’s national renewal through the 2026 NPF consultation’

‘AI regulation is key to Labour’s climate credibility’

Ben Cooper column: ‘Labour needs to rediscover its own authentic populism’