The Labour leadership contest is approaching crunch time. Ballots go out Friday and in the next few weeks the Labour movement will decide who it wants to be its leader. It’s a big decision and it has implications far beyond the 2020 and 2025 General Elections. This is about the very future and purpose of the Labour Party in the 21st Century.

At times this contest has been downright unpleasant. Supporters of Liz Kendall – or in many cases those just not supporting Jeremy Corbyn – have been branded “Tories” or “Neoliberal sell-outs” (whatever that means). Supporters of Jeremy Corbyn have been called “morons” needing “heart transplants”. Whoever wins in September, bringing Labour together and turning it into a credible alternative party of government will be no small task.

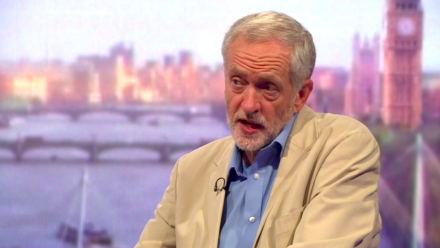

So what should Labour do? In my opinion what happens next is defined by the leader it chooses, and that leader must not be Jeremy Corbyn. The polls suggest I am on the losing side but hear me out. This is my case.

If Jeremy Corbyn is elected in September, it will be the biggest gift that Labour has given the Conservatives in more than 30 years. David Cameron and George Osborne will continue to (successfully) define themselves as providers of ‘security’ against the ‘risk’ of Labour and its new ‘hard-left’ identity.

Labour will have given the public a reason to vote against it and make no mistake they will take it.

In the short term the left will probably feel buoyed. There will likely be more strikes, protests and raucous scenes outside Conservative Party conferences. Politics will be noisier, perhaps even more fun. However, in the longer term, the Conservatives will quietly continue to shape the country in their own image, moving ever rightwards because Labour is unelectable.

‘Corbyn the unelectable’

But can we be sure that a Corbyn-led Labour Party would be unelectable? He has attracted large crowds at his campaign rallies and some of his policies, such as nationalising the railways, seem popular. Furthermore, Corbyn supporters are quick to point out that ‘only 24% of the electorate voted Conservative in 2015’, so surely there are more than enough non-Conservative voters to produce a Labour victory in 2020?

This is the case for Corbyn’s electability and it is built on sand.

Large attendances at campaign rallies are impressive but meaningless as indicators of electability – just ask Michael Foot. Support for policies such as re-nationalising the railways are superficial at best without cost attached to them. There are also plenty of important policy areas where Labour is vulnerable – welfare, public spending and immigration – and a Corbyn victory will not help. This is before we even begin to address his more radical positions such as pulling out of NATO, revisiting Clause 4 and abolishing the Monarchy. On the whole, public opinion is not always Jeremy Corbyn’s friend.

Perhaps the biggest myth of all is this idea of ‘the 76%’, that all Labour needs to do to win is motivate those that did not vote Conservative in 2015.

This position is flawed. It ignores the fact non-voters, if they did show up, would not necessarily flock to Corbyn. UKIP voters are staunchly anti-immigration, the Greens achieved less than 4% of the vote in 2015, the Lib Dems are at their lowest ebb ever, and there is no evidence that promising to abolish Trident defeats the SNP in Scotland. Do these disparate political voices really desire Corbyn’s brand of socialism? Where is the evidence that they can simply be ‘motivated’ to support a far-left Labour Party anyway?

More importantly, this analysis perpetuates the myth that Labour doesn’t need to worry about Conservative voters. The opposite is true. The only way that Labour can win again is by winning over significant numbers of those voting Conservative in 2015 – many of whom will have voted Labour in the past. Analysis by the Fabian Society concludes that four out of five votes that Labour needs to win back in 2020 are Conservative. To win them over, the next Labour leader has to address issues many in the party would rather not, such as public spending, immigration and welfare. Once you accept this, and you really should, it is hard to argue that Jeremy Corbyn is the answer. These people won’t vote for him.

What’s the point in winning?

Even if the electability question was settled, which it isn’t, many on the Labour left will say “what is the point in winning anyway if we are just like the Tories?“ It is a fair question. Let’s deal with it using the recent example of the Welfare Bill.

If there has been a defining moment of this leadership campaign it was when the Shadow Cabinet abstained on the Welfare Bill, and Jeremy Corbyn voted against it. Much has been made of this by Corbyn supporters and it has proven something of a rallying call for his campaign. Privately, Harriet Harman must curse her somewhat strange decision to order Labour MPs to abstain. Rather than demonstrate that Labour was listening to voters on the economy, it seems to have turbo-charged Jeremy Corbyn’s campaign in the opposite direction.

The irony is that Labour will vote against this bill in the end. However, it will be an entirely symbolic gesture. Labour lost the General Election and the reality is that it can do little about Conservative plans for welfare from opposition. For those that oppose what the Conservatives are doing the answer is simple – Labour needs to win next time. Then it gets to shape the welfare system, not the Tories. This is the point of winning.

Herein is the heart of the argument against electing Jeremy Corbyn as Labour leader. He may provide robust and noisy opposition but in opposing everything the Conservatives do Labour risks achieving nothing. Far better to give some ground, accept the principle of a welfare cap for example, earn some credibility with the public and in doing so win and protect against even more harsh welfare cuts in the future.

The alternative is not to address public concerns about Labour’s economic competence at all, lose another election and see the benefit cap fall further with ever more disastrous consequences for Britain’s poor. Today, the Conservatives talk about the unfairness of those on benefits receiving more than the average national wage. In the future might they talk about the unfairness of them earning more than the minimum wage too?

Moving the conversation on

There is another good reason to give some ground on welfare – to move the conversation on. The Conservatives are strong versus Labour on welfare but they are vulnerable in other areas. Their majority is small and they consistently miss economic targets that they set for themselves. However, they get away with it because they can say that Labour would be worse.

This parliament will see further huge spending cuts, an EU referendum and a Conservative leadership contest (probably). The Conservatives are there for the taking and Labour can take them. However, it won’t if it remains stuck on issues such as welfare where it is weak and fights battles on issues that the public do not care about such as renationalising industry or unilateral nuclear disarmament. Such battles will be fought within Labour first and that won’t be pretty either. The upshot is depressingly familiar; Labour won’t be taken seriously by voters and it will lose in 2020.

Here we return to Jeremy Corbyn and ‘electability’. Electability is a complicated concept based on the brands of political parties and their leaders. Labour needs a leader that the public can visualise in Number 10 – someone with a credible vision for Britain and a credible economic policy. ‘Credibility’ is won by showing that you have listened to the voters and are addressing their concerns about Labour. Jeremy Corbyn is not the man for the job.

In the coming weeks, Labour must choose a leader that it thinks can win the next General Election. Otherwise, it will be relegated to shouting from the sidelines whilst the Conservatives shape the country in their image. This article has discussed welfare but there are many other issues too. If Labour gets this leadership election wrong, it will be full steam ahead for the Conservatives.

And time is running out. By 2020, Labour can expect redrawn constituency boundaries and English votes for English laws. If Labour gets too comfortable in opposition it may just stay there – forever. Labour isn’t ‘owed’ a turn at governing in 2020 or 2025. As Labour members vote in this leadership contest they should remember that.

Keiran Pedley is an elections and polling expert at GfK and presenter of the podcast ‘Polling Matters’.

More from LabourList

Nudification apps facilitate digital sexual assault – and they should be banned

Diane Abbott suspended from Labour after defending racism comments

Labour campaign groups join forces to call for reinstatement of MPs