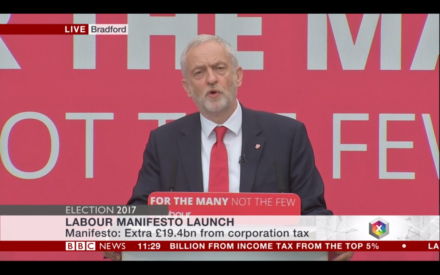

When Labour’s manifesto was published, halfway through the general election campaign, the party was languishing far behind the Tories in the polls. At the time, it seemed fanciful that we could win the election and so it eventually proved. However, at the next general election the prospect of a Labour victory will not be out of this world.

Credit for the turnaround in the left’s electoral fortunes can in large part be given to the manifesto. Indeed, support for our policies was the most common reason that voters gave to pollsters for voting Labour. This is backed up by anecdotal evidence from activists that the manifesto hit the electoral sweet spot. It was also a momentous achievement to prepare a detailed 128 page document at little more than a moment’s notice. The contrast with the Tories’ arrogant minimalist approach was stark. But, electorally successful as Labour’s 2017 manifesto was, there is a big difference between writing a manifesto for opposition and one to be implemented by a government.

Next time, difficult decisions will need to be made, not least on tax and spending. The respected Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) said that both the Labour and Tory 2017 manifestos did not set out an honest set of choices. The IFS went on to say of Labour’s proposed spending: “the pretence is that can all be funded by faceless corporations and ‘the rich’. The case [for higher taxes] needs to be made with honesty about what it would mean for tax payments, not pretending that everything can be paid for by ‘someone else’.”

For the next manifesto Labour needs to ensure this criticism cannot be made of us. That will involve going through our costings in detail and being more realistic about levels of revenue and spending.

One example is the unanswered question of how the string of proposed nationalisations contained in the 2017 manifesto are to be paid for. These are potentially huge changes to the British economy and yet we were not clear about how they would be executed. Overall, Labour’s plans for policy implementation fall into the “must try harder” category.

The experience with historic student debt ought to be a cautionary tale. Labour’s 2017 manifesto promised to abolish tuition fees, an ambitious and expensive promise in itself, but stopped short of promising a write-off of student debt. Nevertheless Jeremy Corbyn said he would “deal with” student debt, giving the impression that a write-off was in the offing. Since the election there have been calls of “betrayal” but how much louder would they be if Labour was now in government? You can ask the Liberal Democrats for the answer.

At the next general election, Labour’s challenge is to retain the appeal of its 2017 manifesto while developing a programme that can actually be implemented in government. Making Labour fit for government does not necessarily mean “shrinking” the offer.

It is possible to have a radical and ambitious programme that is also honest and implementable. The Labour 1945 manifesto achieved this, as did, in a different way, the one for 1997. In contrast, the 2001 Labour manifesto promised not to introduce top-fees only for them to be brought in. Breaking this promise was surely one of the key causes of our demise from government. For the next election, the party needs to think not just about the tactics of winning the election over a few weeks but strategically about how to govern successfully for years.

The dangers of going into the next general election with an undeliverable manifesto are clear. Firstly, in principle we should be up front and honest with the voters. Labour should never be in the position of winning an election only to renege on its promises. That is what the Lib Dems are for. Secondly, as Labour is seen as a potential government, the next manifesto will come under much greater scrutiny than the last one from voters and the media. It will not be so easy to gloss over serious questions like how proposed nationalisations will be paid for. Thirdly, it would be a disaster if Labour was to be elected on a false prospectus. Not only could it lead to a decimation similar to that of the Lib Dems, who were punished for their student fees betrayal, but it could lead to chaotic government and damage to the economy.

At a time of such cynicism about politics, Jeremy Corbyn has attracted and enthused millions. In that spirit, he has called for “straight talking, honest politics”. Let us apply that motto to our next manifesto and put it into practice in government.

Omar Salem is a Labour Party member in Hackney South and Shoreditch.

More from LabourList

Nudification apps facilitate digital sexual assault – and they should be banned

Diane Abbott suspended from Labour after defending racism comments

Labour campaign groups join forces to call for reinstatement of MPs